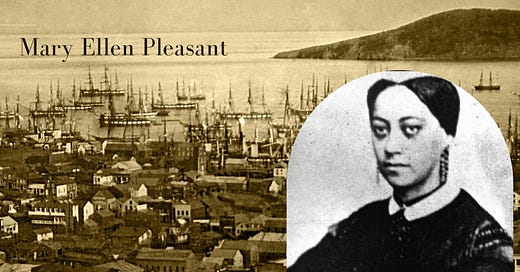

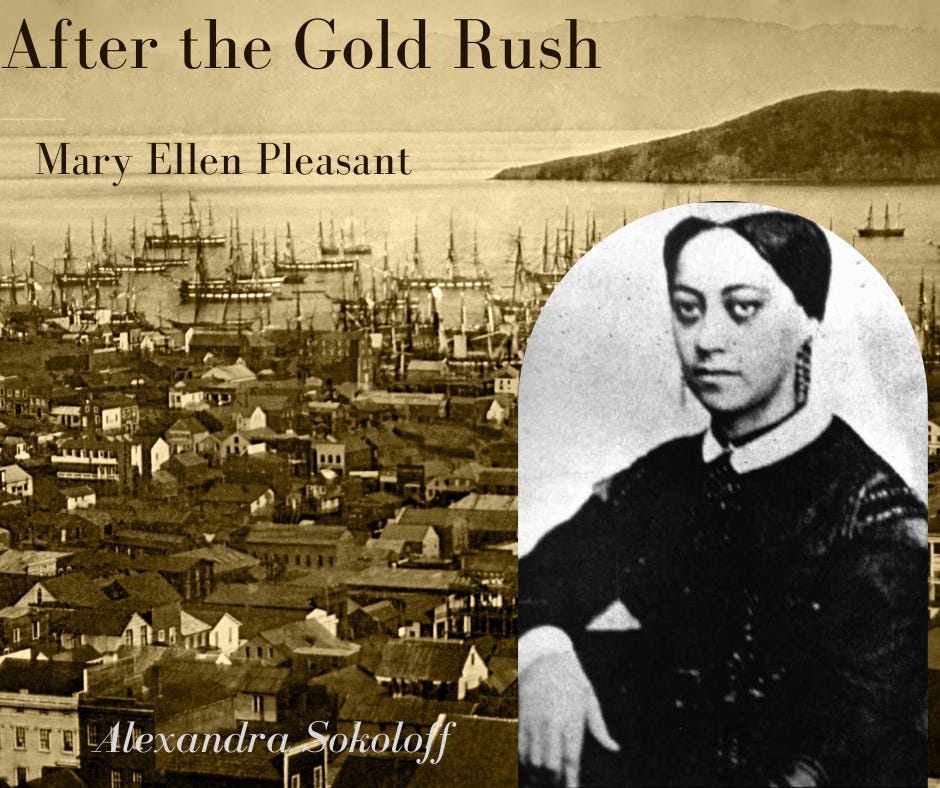

Black entrepreneur Mary Ellen Pleasant in Civil War San Francisco

One of the most fascinating and contradictory figures of San Francisco’s riveting history is Mary Ellen Pleasant. By current standards she was one of the first Black US millionaires, owning extensive property and businesses and employing dozens of Black workers who escaped the South to California via the Underground Railroad.

She worked for some of the most powerful men in the city and is said to have parlayed business and stock tips she picked up from the dinners she served them into her own fortune.

She was hailed as the “Mother of Civil Rights” in California (a key anti-discrimination bill is named for her) and demonized by the white newspapers as a seductive con artist, a madam, a “baby farmer,” and a sinister voodoo queen. Even physical descriptions of her are conflicting: although for her first decade in San Francisco, pre-Emancipation, she passed as white—she has also been described by contemporaries as “coal black.”

She wrote her own autobiography three times, all of them conflicting, none of them preserved in entirety.

In a time when the full history of the United States is under attack, it’s more important than ever to tell the stories that the book-banners and the history whitewashers want to erase.

Mary Ellen’s starts here.

After the Gold Rush, Chapter 43

October, 1861 - San Francisco, California

Mary Ellen Pleasant:

On October 24, 1861, the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Line from New York to San Francisco was complete, and the isolation of California was shattered. Weekly newspapers became daily papers. It created a national conversation. It also forged a psychological link in California hearts, that East and West were one.

Now we had hourly news of the war, and felt the same urgencies. The news wasn’t good.

Especially that Union General McClellan seemed to balk at fighting.

I read the accounts and could not fathom the man’s seeming popularity. At the rate he was avoiding actual conflict, the war could go on forever with nothing changed. The South was racking up victories.

But practically, for the most part, California tended her own fire.

While the war raged, devastating the South and draining the coffers of the North, our isolation created a booming economy. Of course it did. Our industries had no competition from Eastern products. We grew our own food, harvested our own timber, raised our own livestock.

Also, Lincoln never did impose the draft in California. It was partly to keep the far West loyal—he must have known at least something of treasonous Senator Gwin and the secessionist Knights of the Golden Circle. But realistically, the West was funding the Union’s war, by mining gold and sending it North to fill the Union’s war chest.

And one very good thing came out of the war that year—for me.

Selim Woodworth went out to the Union Navy as an acting lieutenant. And I moved into the Woodworth mansion to run it for Lisette. It was an extensive estate. You can imagine Selim felt a lot better going off to war knowing Lisette would be well-looked after. They hadn’t announced it yet, but she had a baby on the way. She looked beautiful, too, her face round and radiant.

I was pleased with my work—it had been a perfect match. It was mighty interesting, to me. If you’ll remember, Selim was from a prominent family. He could easily have dug around, found Lisette out, even with the careful web of family histories and marriage connections I’d woven for her to tell him. Far as I know he never asked. Or if he did, he never did anything with it. Lisette was young, and pretty, and healthy, and fertile. She was also smart, determined, and a true survivor. I hadn’t picked her out of the gutter for nothing.

And Selim was a truly good man: kind, generous, and moral. He was passionately committed to a more equal society, willing to lay his life on the line for abolition.

With Selim gone, Lisette was left to entertain all their society friends. And I was there to help her make out the guest list.

I had three laundries by now, my first on Jessie and Ecker, one on Clara Street, and one farther out of the city, out on Geneva and San Jose Road, that serviced the Pacific mail steamers. I was looking at bigger properties, too, with an eye to acquiring my first boarding house.

So why would I want to be a housekeeper?

For cover, obviously. My husband was permanently at sea, and I was fine with that. I didn’t expect Jean back, and I wouldn’t have him that way again even if he did show up. Not with the kind of diseases career sailors picked up.

But women just didn’t live alone in San Francisco. In actual fact, men rarely did, either. I couldn’t afford to draw attention to myself. Being in-house at the Woodworths gave me all the respectability I could ask for, for myself and for my businesses. It was the ultimate pass, and I needed to pass.

The whole white system depended on me being enslaved. I came as far as I could get to get away from it, but there were plenty of people in California who were going to do their damn best to bring some version of slavery with them. I was going to make it work for me.

I would make them work for me.

At the Woodworth’s, like at the Ralston’s, I had a steady stream of powerful men right in front of me, talking business half the night long.

I loved setting a plate in front of one of those bankers and have him not even notice me— while I knew that he was going to make me money.

My contacts kept me in the loop about politics, too.

My sources all said that the that secessionist Asbury Harpending and the Knights of the Golden Circle had gone quiet. I wanted to believe it… but I needed to be sure. So I got Lisette to have the Ralstons for dinner.

William Ralston was in the middle of everything. He was now treasurer of the Ophir Gold and Silver Mining Company, and of the Gould & Curry. On the Boards of Directors of both California’s new telegraphic companies. Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Chamber of Commerce. In June, he completed a bank merger, and Fretz & Ralston became Donahoe, Ralston & Co., operating on both coasts.

Like I said. The man knew how to make money.

To be fair, Ralston was also very busy collecting for the Sanitary Commission, that cared for sick and wounded Union soldiers. Donating a hundred thousand dollars from his own company. Coordinating fundraising drives with Reverend Starr King, who was beyond reproach. Mostly due to the two of them, California was supplying a quarter of the total Sanitary fund. During the Sacramento flooding, Ralston arranged for donations there, too, and cut another hundred-thousand dollar check from his own bank.

It’s not hard to be generous when you’re making a mint. But lots of people wouldn’t bother.

And I reveled in Ralston’s success. Because I could feel it coming for me. One day soon, the man was going to make me a mint, too.

After supper, when I brought Ralston his favorite brandy, I asked after Harpending, casually remarking that I hadn’t seen him of late.

Ralston took an appreciative sip from his glass. “I believe Mr. Harpending has moved on.”

He looked at me directly, and I was suddenly sure he knew a lot more about me than he had ever let on. I wondered just how long he’d known.

He continued, casually. “I have it on good authority that the Knights of the Golden Circle have folded their tent.”

I was keen to know where he really stood, and relief made me bold. “Good news for California.”

“It is.”

“What discouraged them, I wonder?”

His eyes twinkled. “It was the Comstock. Simple greed. Secesh in California know they’re going to make so much money in the mines that they find it hard to fight for their ‘peculiar institution.’ Apparently Harpending has left the state and traveled by steamer to Acapulco. Good riddance,” he added.

I couldn’t have agreed more. But I knew we hadn’t seen the last of him.

So the year almost ended on a high note. And then on October 29th, 1861, Robert Schell, a white man, walked into a barbershop owned by George Gordon, one of our most prominent Black businessmen and civil rights activists, and pulled a gun.

The night before, Schell had robbed the shop next door, a millinery store run by Gordon’s sister. She chased him into the street, crying “Stop, thief!” but was not able to overtaken him.

This crazy man Schell came back the next day with a gun and stormed into Gordon’s barber shop, demanding that Gordon make his sister take back the insult of “thief.” When Gordon replied he had nothing to do with the affair, Schell up and shot him. Gordon ran into the street, and in front of multiple witnesses, Schell pistol-whipped him and shot him again, killing him.

The murder caused an outpouring of grief in the community—and in our allies. Reverend Starr King protested the injustice by officiating at Gordon’s funeral services, drawing his own crowds to mourn.

But at Schell’s trial, the judge refused to allow almost every eyewitness to give evidence, citing California’s laws forbidding testimony by Blacks against whites.

An Act Concerning Crimes and Punishment:

No black or mulatto person, or Indian, shall be allowed to give evidence in favor of or against a white man. —California Book of Statutes, 1850, Chapter 99

And then when the prosecutor called James Cowes, the one white man who had witnessed the murder, Schell’s attorney claimed Cowes was really Black, and brought in so-called experts in “racial science” to examine him. The judge allowed a full, humiliating examination of Cowes’ body hair, and the “experts” concluded Cowes was one-sixteenth Black. Cowes was barred from testifying, and Schell got just two years for cold-blooded murder.

As the trial adjourned, Philip Bell, J.J. Moore, James Madison Bell and the rest of the Executive Committee were already making furious plans.

The double outrage of the murder and the sham of a trial caused a public outcry. The use of “hairology” to prove racial heritage was widely mocked in the newspapers. The Executive Committee seized on the incident to try to convince influential white San Franciscans to oppose the testimony exclusion laws. They got up a petition for a bill to rescind the ban on Black testimony, intending to find a congressman to present it.

It put me in a bind. I knew they were looking to me to bring them some names. I had the contacts—but advancing the petition put me at risk of exposure.

As it turned out, I didn’t have to do it myself. Lisette came to me about it.

“I want to help with the petition.”

I was caught off-guard. “What petition?”

She looked at me steadily. “To rescind the ban on colored testimony. I know you can’t talk to people about it, but I can. Selim would want to help. I want to help.”

And it dawned on me that by taking a chance on Lisette, I’d chosen better than I’d even known.

San Francisco, California

Asbury Harpending & the Knights of the Golden Circle

Asbury Harpending: Our plans to seize the Presidio having been thwarted, the Knights had a succession of meetings to regroup. Certainly we had the organized forces to carry out our plans.

However, there emerged another very disturbing factor—the Comstock Lode.

That marvelous mineral treasure house began to open up new stores of wealth. Speculation was enormous. The opportunity for making money seemed without limit. Many of the Knights were deeply interested.

Now, it had been determined absolutely from the outset that our ambitions were to be bounded by the easily defended Sierra. We knew enough about strategy to understand that it would be simple madness to cross the mountains. That meant, of course, the abandonment of Nevada.

This had been accepted with resignation when the great mines were considered played out. But when it became apparent that the surface had been barely scratched and that the secession of California might mean the casting aside of wealth beyond the dreams of avarice, then patriotism and self-interest surely had a lively tussle.

If Nevada could have been carried out of the Union along with California, I am almost certain that the story would have been widely different. That’s the only way I can size up what followed. The meetings began to lack snap and enthusiasm. Just when we should have been active and resolute, something always hung fire.

The last night we met, the face of our General was careworn. After the usual oath, he addressed the committee.

“It is plain, that the members are no longer of one mind. The time has come for definite action, one way or another.”

He proposed to take a secret ballot that would be conclusive.

The word “yes” was written on thirty slips of paper; likewise the word “no.” The slips were jumbled up together and were placed alongside of a hat in a recess of the large room. Each member stepped forward and dropped a slip in the hat. “Yes” meant action; “no”— disbandment.

When all had voted, the General took the hat, opened the ballots and tallied them; then threw everything in the fire.

He turned to the room.

“I have to announce,” he said, “that a majority have voted ‘no.’ I therefore direct that all our forces be dispersed and declare this committee adjourned without delay.”

My heart sank.

Not another word was spoken. One by one the members departed.

Two days later, all the various bands had been paid off and dispersed. Only the General knew the extent of the disbursements. My own impression is that they far exceeded a million dollars. I had contributed $100,000 myself.

The “great conspiracy” had vanished into the vast, silent limbo of the past.

I would have to find another way.

From: The Great Diamond Hoax and Other Stirring Incidents in the Life of Asbury Harpending

Full book available at Project Gutenberg

Keep reading:

Why subscribe?

After the Gold Rush is a reader-supported publication. To receive a monthly roundup of new posts and support this work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Feedback, Comments, Likes and Shares are hugely helpful and much appreciated!