The California Gold Rush began in 1849 with a wild race across the country and the world by individual fortune seekers seeking to pan gold out of the rivers and sift it out of the sand. By 1855 the Rush was over: surface gold had been scooped up, and gold mining was only possible for wealthy investors who could afford to build the machinery now required to mine. But the Silver Rush had already begun, and it would prove far more lucrative to California than the Gold Rush ever had—even though the actual silver mines were in the Nevada Territory, deep in a desert mountain known as the Comstock. The Comstock was so entwined with San Francisco life and commerce that the two were referred to as “Above” (the Comstock) and “Below” (San Francisco) — and the continuous wagon train traffic from Sacramento to Virginia City rivaled any freeway gridlock in the Bay Area today! George Hearst made his fortune here; Samuel Clemens became Mark Twain here after he ditched his extremely failed dream of silver mining to write for the Territorial Enterprise. And it was here that Jewish immigrant, future mayor of San Francisco and philanthropist Adoph Sutro conceived an engineering project that would pit him against the most powerful robber barons of the West.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Chapter 18

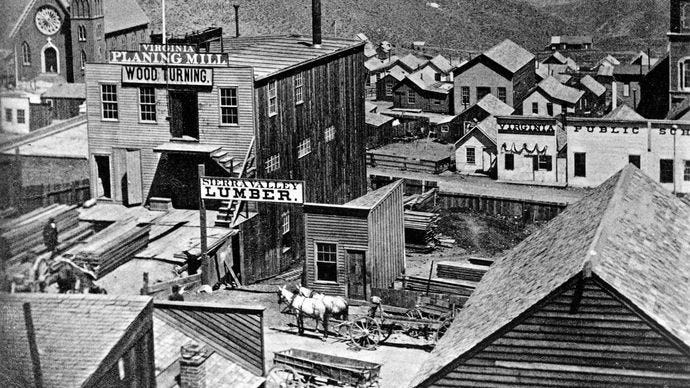

Spring, 1860: Virginia City, Nevada

Adolph Sutro, George Hearst

The 'city' of Virginia roosts royally midway up the steep side of Mount Davidson… and in the clear Nevada atmosphere is visible from a distance of fifty miles! It claims a population of fifteen thousand to eighteen thousand, and all day long half of this little army swarms the streets like bees and the other half swarms among the drifts and tunnels of the 'Comstock,' hundreds of feet down in the earth directly under those same streets. Often we feel our chairs jar, and hear the faint boom of a blast down in the bowels of the earth under the office.

There, a great population of men throngs in and out among an intricate maze of tunnels and drifts, flitting hither and thither under a winking sparkle of lights, and over their heads tower a vast web of interlocking timbers that hold the walls of the gutted Comstock apart. These timbers are as large as a man's body, and the framework stretches upward so far that no eye can pierce to its top through the closing gloom. It is like peering up through the clean-picked ribs and bones of some colossal skeleton. A framework two miles long, sixty feet wide, and higher than any church spire in America.

The Gould & Curry is only one single mine under there, among a great many others; yet the Gould & Curry's streets of dismal drifts and tunnels are five miles in extent, altogether, and its population five hundred miners. Taken as a whole, the underground city has some thirty miles of streets and a population of five or six thousand. Some of those populations are at work from twelve to sixteen hundred feet under Virginia and Gold Hill, and the signal-bells that tell them what the superintendent above ground desires them to do are struck by telegraph as we strike a fire alarm. Sometimes men fall down a shaft, there, a thousand feet deep. In such cases, the usual plan is to hold an inquest.

If you wish to visit one of those mines, you may walk through a tunnel about half a mile long if you prefer it, or you may take the quicker plan of shooting like a dart down a shaft, on a small platform. It is like tumbling down through an empty steeple, feet first. When you reach the bottom, you take a candle and tramp through drifts and tunnels where throngs of men are digging and blasting; you watch them send up tubs full of great lumps of stone—silver ore. You select choice specimens from the mass, as souvenirs; you admire the world of skeleton timbering; you reflect frequently that you are buried under a mountain, a thousand feet below daylight; being in the bottom of the mine you climb from "gallery" to "gallery," up endless ladders that stand straight up and down.

When your legs fail you at last, you lie down in a small box-car in a cramped "incline" like a half-up-ended sewer and are dragged up to daylight feeling as if you are crawling through a coffin that has no end to it. Arrived at the top, you find a busy crowd of men receiving the ascending cars and tubs and dumping the ore from an elevation into long rows of bins capable of holding half a dozen tons each; under the bins are rows of wagons loading from chutes and trap-doors in the bins, and down the long street is a procession of these wagons wending toward the silver mills with their rich freight.

Nevada produces $20-25,000,000 in bullion—almost, if not quite, a round million to each thousand inhabitants, which is very well, considering that she is without agriculture and manufactures. Silver mining is her sole productive industry.

- Mark Twain, the Territorial Enterprise

The Silver Rush was on. Half of San Francisco relocated to the Comstock and the other half was doing business there.

Adolph Sutro was one of the thousands of Californians who left their wives and families in San Francisco and made the Nevada Territory their second home.

Since his arrival in San Francisco and his venture into the Barbary Coast, Sutro had trod the straight and narrow path. In a few short years he’d accumulated enough capital to open his own dry goods shop, where he sold provisions ranging from boots and cloth to lager. He parlayed this into three profitable tobacco shops, became a U.S. citizen, and married Leah Harris, a practical and devout young Jewish Londoner. Together they used the money from Adolph’s cigar shops to invest in the profitable business of rooming houses, which Leah proved adept at managing.

But the lure of the new silver mines was too powerful to resist.

Sutro enlisted cousins to tend to his three stores in San Francisco, left Leah in charge of the boarding houses, and moved to Virginia City to set up a cigar store.

It was a five-day journey first by ferry to Sacramento, then by stagecoach or wagon, up over the Sierras to Virginia City and its scruffier neighbor Gold Hill. Together known as the Comstock, or Washoe, the towns became a literal extension of San Francisco, crowded with miners, gamblers, Chinese laborers, and speculating merchants. Wagons stretched in a nearly continuous line on the two-hundred-sixty-mile journey, all headed for a city of perhaps 20,000 people in the middle of nowhere.

There were breathtaking natural vistas, clear mountain air and the scents of juniper and sagebrush. There was also barely any drinkable water; the temperature could vary by 50 degrees daily; and the city was plagued by “Washoe Zephyrs”—scouring afternoon winds billowing sand, shaking buildings, peppering windows, and carrying away loose clothing, small dogs, and anything else not nailed down.

Washoe Zephyr, illustration from Roughing It

Adolph described the town in a letter to his mother:

“Virginia City is located on the eastern slope of a range of hills, which run from north to south, and which contains the far-famed Comstock Lode. The streets run parallel with the Lode, and there are three of them laid out, A, B, and C Streets; lots running from street to street, being one hundred feet in depth. No cross-streets are provided for. The uppermost street is called the “Exchange,” for the “honest miners,” and the “speculators,” and the “sharpers,” and everybody else meet there to trade in claims, swap them off for others, “bull and bear” mining stock, take in some greenhorns, and, after all, transact considerable bona fide business. Some days, the trade consummated on the Exchange would compare with the transactions on Front Street in San Francisco; but where there is such a mixed crowd of people, there must naturally be a good deal of humbug. The living is somewhat of the ’49 style in California. There are very fair eating houses, where everything that the market affords is provided. I am sorry to say that the market affords but very little; beef, pork, beans, and rice are the staples.”

He’d brought the five-foot-high automaton he’d used to attract customers in San Francisco, and set it up in front of his new store. The mechanical man held a large tobacco pipe between its lips and puffed away, controlled by a counterweight tied to a string.

Inside Adolph did a brisk business in cigars, tobacco, and meerschaum pipes. So far he’d resisted the temptation to speculate on the mines, even though it seemed everyone in both cities, Virginia and San Francisco, was doing it. But Adolph was rational enough to realize not everyone was a George Hearst. Indeed, almost no one was.

That preternaturally gifted miner had taken on the supervising of the Gould & Curry mine, just up the street. Sutro could daily observe Hearst welcoming investors to the opulent building of the offices where the mine did business. The Gould & Curry wasn’t yet anywhere near the production of the Ophir, but if there was anyone in the Comstock who understood mining, Sutro would bet on Hearst.

Every month, hundreds of would-be miners with no such gifts continued to trudge up the canyons, only to discover the only way left to own one of the new mines was to buy one’s way in. They grudgingly hired out themselves out as labor, using their earnings to purchase “feet” of the mines, or taking their stakes to try prospecting in nearby mountains.

All those hopefuls needed their staples, including the pleasure of a good cigar, and Sutro’s shop was doing well.

But Adolph was also re-discovering his early interest in engineering. As a child he’d been fascinated by the machines of his father’s woolen factory. When he and his brother Sali had taken over the mill, Adolph had developed his mechanical skills by constructing a pipeline to channel water to the mill from a brook, and building an iron forge.

Now his engineering instincts led him to make copious notes on what he considered the inefficiency of the Comstock mining operations

“…The mine-working is done without any system as yet. Most of the companies commence without an eye to future success; instead of running a tunnel low down on the bed, and thus sinking a shaft to meet it, which at once insures drainage, ventilation and facilitates the work, by going upwards, the claims are mostly entered from above, large openings made which require considerable timbering, and which expose the mine to wind and weather.

A railroad from Virginia City to Carson River, some seven miles distant, could be built at a very small expense, the country sloping gently down towards it. The cars loaded with ore could be made to pull up the empty train, and the ore, once at the river, can be easily worked.”

There was also the troubling question of the dangers that mining posed to the miners, a catalog of horrors to challenge Dante’s tour through the Inferno. Besides falling down a mineshaft, miners could be—and routinely were—torn to shreds by premature explosions of blasting materials, roasted in underground fires, hit by falling equipment, or crushed by a runaway ore car.

Also, because the miners had to go so deep underground to reach lucrative lodes of ore, they often suffered or even died due to the incredible heat—up to 140 degrees—and poisonous gasses. In some mines, laborers could only work for fifteen minutes before having to return to the surface to breathe air and recover. Down in the mines they spent most of their time just gulping in air at a shaft. They kept ice in their clothing, ate it constantly.

On top of the heat, there was a dangerous excess of water underground at all the mines. Floods of scalding water were common and miners were often imperiled when vast underground reservoirs were unexpectedly tapped.

On one particular morning, Sutro had just descended the stairs from his rooms to open the shop, when he felt the earth shake beneath him. He froze in anticipation of the temblor…

Then he remembered this was Virginia City. The town was host to a whole different set of tremors, the rhythmic chugging of hundreds of pumps, the explosions from the blasting constantly going off in the mines. That was in addition to the constant noise from mines and ore mills, from horses galloping through town, rattling wagons, shouts from saloons and brothels…

Adolph frowned, listening.

There was something different about the shouts he was now hearing.

And then the sirens went off.

Adolph bolted for his front door and out onto the street. The chill morning air hit him as he cast his eye down the steep hill.

In the parallel street below a wagon trundled by, going far too fast. Adolph started back in horror. The wagon was piled with the bodies of men, horribly burned, their faces half broiled off.

Sutro understood instantly what had transpired. An underground reservoir. A flood of scalding water.

Another wagon rumbled after the first, with the same pathetic cargo. Adolph stared down at the ruined men.

This is insufferable, he thought. It is inhuman. It is madness.

And then—

I won’t have it.

He spent the rest of the day obtaining maps of the mines. Over the next weeks, he made a series of sketches of one long tunnel underneath the Comstock Lode at its lowest point, that could be connected with the shafts of each of the numerous mining companies. The tunnel would serve as a ventilation shaft, cooling the air, and a drainage system to reduce the boiling water,and also provide an alternate escape route in case of fire or tunnel collapse. All functions would work together to make mine workers more productive and almost certainly reducing the risk to life and limb. And it would pay for its own operation by serving as a transportation tunnel for mined ore.

He was suddenly struck by the memory of a quote from his childhood studies, and spoke it softly to himself. “And who knows but that you have come to the Kingdom for such a time as this and for this very occasion?"

He reached for fresh paper and began a letter to the Alta California—to propose the Sutro Tunnel.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

How did they have ice to bring down into the mines?? Refrigeration wasn't invented yet, right? The horrors to which people have subjected themselves in pursuit of money are beyond astonishing.