Before and during the Civil War, powerful Southern forces (including the ruthless Senator William Gwin from Mississippi, elected to “represent” California) were working to turn California into a slave state. When the war started, San Francisco business leaders and citizens rallied forces to stop the plans of the Knights of the Golden Circle, secessionists in California who sought Confederate control over California and her wealth. “With the city of San Francisco and her impregnable fortifications in Southern hands, the outward flow of gold, on which the Union cause will depend in a large measure, would cease—as a stream of water is shut off by turning a faucet.”

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Chapter 20

Summer 1860: San Francisco, California

Mary Ellen Pleasant

William Ralston, Selim Woodworth, Asbury Harpending, James Madison Bell, JJ Moore, Peter Anderson, The Executive Committee

After the nomination of Lincoln, it seemed everything was politics. But I tried not to get too involved.

My two business models were coming together. I had more work than I could handle from rich families who wanted my cooking, catering and party planning. I guess you could say I was a steward-at-large: supervising a number of households, organizing and supplementing their regular staff for larger events.

Milton Latham, now Senator Latham, had moved on to serve in Washington, but not before he’d opened all kinds of doors for me. Including the Ralstons’. As soon as Latham was gone, Mr. William Ralston snapped me up, and I was right where I wanted to be: in their grand house on fashionable Rincon Hill, catering events for him and his wife Lizzie.

I’d been right about Ralston. He was one of them who got a taste for New Orleans when he was working on the Mississippi, a taste for the food, a taste for the beauty and revelry, a taste for the strange.

Everything I knew how to give a man.

I cooked my way right into his good graces. I made sure of that.

For one thing, the Railroad was getting escaped slaves to California every month. The more powerful people I worked for, the more of our people I could put to work as cooks, servers, decorators, seamstresses—in boarding houses and private houses and shops and liveries all over town.

I won’t lie. I figured it would pay off for me, too, having all those eyes and ears in all kinds of places. And of all the best houses in the City, the Ralstons’ was the hub.

The Ralstons were host to all sorts. Some very interesting people were showing up at these dinners. After Abe Lincoln came from behind everyone and won the Republican nomination, every businessman in San Francisco was desperate for any hint of which way the winds were blowing. There were gatherings at the Ralstons’ most every week.

I cooked my heart out. Venison and game from Marin County, butter from Point Reyes, vegetables from Mission Bay gardens, fat ducks from the nearby marshes. I experimented with exotic seasonings from Chinese groceries.

Food is a drug, works just like any other. Get people warm and comfortable and glowing, they talk. Oh, how they talk. I kept the courses coming, served ’em up myself so I could hear every word. My special elderberry cordial, laced with opium, helped loosen folks up even more.

And I was paying a whole lot of attention to Mr. William Ralston.

I liked him. Pretty near everybody did. Not just because he was big and handsome. He had wonderful manners, frank, cordial, magnetic—he leaned in and listened when you talked. And handed out the same to everybody.

I also liked his business model. Ralston thought big. He had the grandest of ideas. But I liked his whole way of doing business.

I opened up an account at his bank, Fretz & Ralston, just to watch him in action. He went around to all his businesses, talked to the workers about their jobs and families. He knew half the working population by their first names, and they all called him Billy. Every day he set a spare hour where folks could just come in and tell him their ideas, and he’d back ’em. He was their constant provider, philosopher, and friend.

I figured it was exactly what I wanted to do for Black folks. I figured I’d have some of that for myself.

I said I liked him. That doesn’t mean I trusted him. He had “Southern sympathies.” I didn’t know for sure, but my guess was he voted Cavalier.

But the man built things. And everything he touched turned to money.

That’s a man I want to be around.

That’s a man I want working for me.

The political gatherings at his home were just as interesting. Making money was a top priority. Keeping an ear out for my own survival was even higher.

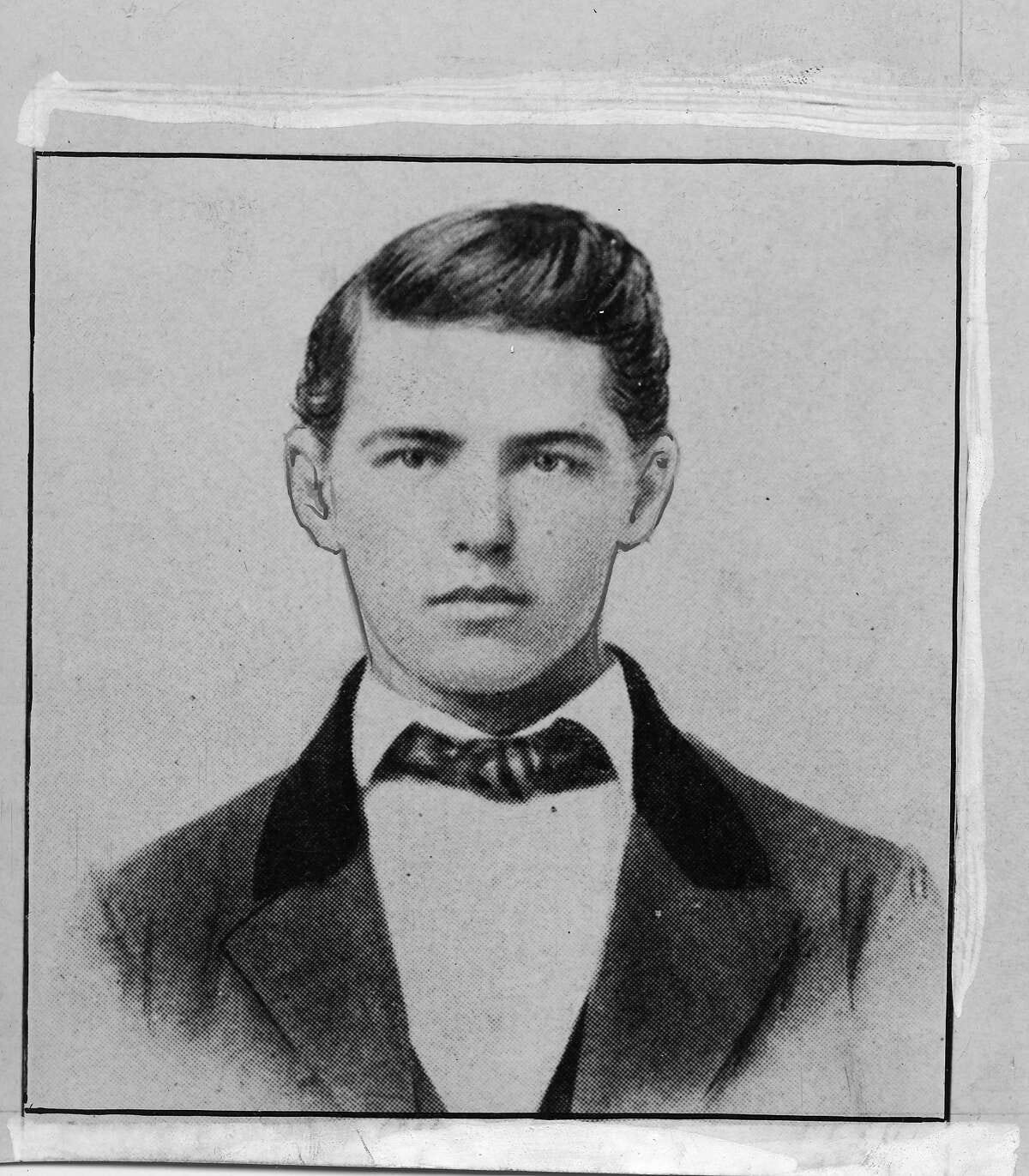

That’s how I came to know a newcomer in town: Asbury Harpending. Twenty-three years old and pure Southern slaveholding stock. His daddy was the largest landowner in Kentucky. Young Harpending took no pains to conceal it.

The boy was reckless—and dangerous. At just fifteen years old he’d run away from home to join that crazy man William Walker in an attempt to overthrow the government of Nicaragua. After that, Harpending’s daddy sent him to California to keep him out of prison. On his way to California he lost his daddy’s stake by speculating, then got it back by selling oranges and bananas on the stranded ship, then made a quarter of a million in Mexico investing in a Mexican gold mine.

He came to California before he was twenty, with that quarter of a million in ore.

Well, no one in San Francisco ignores someone with that much cash. Wasn’t long before he showed up at one of the Ralstons’ dinner parties one night. From the start, I didn’t like the way he looked at me.

And that was even before he showed his politics.

The Democrats were in the process of losing the election all by themselves. They’d split their party right in two and—incredibly—went on to hold two different conventions. The official Democratic convention had reconvened in Baltimore on June 18, and Douglas was nominated for president on the second ballot. But lots of the Southern delegates refused to participate. A group of ’em met in their own separate convention, adopted a pro-slavery platform, and nominated the incumbent vice president, John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky, for president, and Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon for vice president.

That was just the beginning of the crazy. A third party broke off: The Constitutional Union Party, who were gambling they could just leave the question of slavery completely out of the election.

By mid-summer tension was so high, the air was fairly crackling.

And all that was playing out the night Harpending came to dinner. It was business, just three of them: Ralston, Selim Woodworth, and Harpending; and I served the men myself so I could watch and learn. I wouldn’t be bantering back tonight. Tonight I barely stirred the air as I moved through the room.

The conversation predictably turned to the Republican nomination. It was volatile, all right, with Selim Woodworth there, staunch abolitionist; and Harpending, as Cavalier Sesech as a Southern boy could get.

Add to that, he couldn’t hold his liquor to save his life. Halfway through the meal, Harpending was drunk and swaggering, shouting that Lincoln had won the nomination by “pure nigger luck,” and vowing, “We will put down all attempts by Northern fanatics to interfere with the Constitutional rights of the South.”

“You are not in the South, Harpending.” That was Woodworth. His face was like carved ice.

Harpending just scoffed. “Thousands here are tired of being ruled from a distance of thousands of miles. Do you doubt that a ‘Republic of the Pacific’ will be well-received?”

“A Republic including slavery,” Woodworth said. You could hear his contempt.

“Naturally. It is our Constitutional right.”

As I moved about the table, refilling wine glasses, Ralston remained silent, just watching the other two men.

Harpending’s face was bright red, and he smacked the table for emphasis. “The South will not live any longer under a government whose citizens regard John Brown as a martyr and a Christian hero.”

I froze at the mention of Brown. Woodworth was answering, but his words were lost on me as Harpending gave me a sharp, sudden look.

I could not stay longer without seeming to be listening to the conversation. I slipped out. But I could not afford to miss what they were saying. My survival in this city might well depend on it.

So I stayed in the hallway outside, standing against the wall, as quiet as years of hiding had taught me to be.

I could hear Harpending breathing heavily as he continued his rant against Brown.

“You have seen how they have made a martyr out of that fanatic. This talk by Black Republicans of the old man ‘making the gallows as glorious as the cross.’ Ministers preaching of him in commemoration, blaspheming him as ‘a crucified hero.’ Making the word treason holy in the American language—”

“I do not condone Brown’s violence.” Woodworth’s voice was strained. “But the principle—”

There was a slap as sharp as the crack of a pistol. Harpending was pounding on the table again. He talked right through Woodworth. “We regard every man who does not boldly declare that he believes African slavery to be a social, moral, and political blessing—as an enemy to the institutions of the South.”

There was a loaded silence, before Woodworth spoke softly. “You misjudge your listeners, Harpending. Even with Gwin’s packing the offices and the courts, the question of slavery was decided here long ago.”

Harpending’s voice got even louder, a threatening bluster. “Careful what you say of our Senator Gwin, Woodworth. Have you not learned the lesson Terry taught the late Senator Broderick?”

Behind the wall, I caught my breath. Harpending was deliberately steering toward a challenge.

Thankfully, Ralston stepped in. His voice brooked no argument. “I shan’t have such stupidity in my house. Honor can hardly be proven by a keen blade or a well-placed bullet.”

“Well said, Ralston.” That was Woodworth. “And on that, I’ll take my leave.”

I quickly moved back toward the kitchen, and stopped inside an inner hall. I waited, heard footsteps in the corridor, two sets. Then Woodworth’s voice. “I won’t come again, with Harpending here.”

Then Ralston. “He’s a boy. He talks—”

“Not just talk. The Knights of the Golden Circle are no laughing matter.” I dared to peer out and saw Woodworth give Ralston a level look. “I hope you are not among them.”

“Of course not. You know I avoid politics when I can—”

Woodworth was so agitated he did not let Ralston finish. “You cannot. It does not need a military expert to discern what a vital advantage to the secessionists control over the Pacific would prove. With the city of San Francisco and her impregnable fortifications in Southern hands, the outward flow of gold, on which the Union cause will depend in a large measure, would cease—as a stream of water is shut off by turning a faucet.”

The thought was so immediately horrifying I barely heard Woodworth’s final sentence.

“It should then be the easiest thing in the world to open and maintain connection through savage Arizona into Texas.”

“A dire prediction, Woodworth,” Ralston said, attempting levity.

“The time has come that everyone must choose,” Woodworth answered ominously. And I heard his steps, fading down the hall.

My heart was pounding so, I was afraid they could hear it from the inner room. I felt my way back through the hall to the kitchens.

This talk of John Brown. It was madness to think Harpending had any idea of my role in that insurrection…

And yet suddenly to be surrounded by bankers, who might trace my transactions, seemed to me the height of peril. And there were others of us in the same danger. My thoughts flickered to James Madison Bell.

Woodworth had spoken of the “Knights of the Golden Circle.” It was one of those Cavalier names—for men up to no earthly good.

I was so deep in thought I was caught unawares. I heard a step and looked up to see Harpending, swaying drunkenly in the doorway. He’d found me alone in the kitchen.

“I’ve been thinking on you, Mrs. Smith.”

His tone was a challenge and I knew there was going to be trouble. Going for my own knife under the bright lamps of the kitchen would be a risky move. But the knife block on the work table was almost within reach…

He seemed to guess my thoughts. He took a sudden step forward, blocking my path to the knives.

“You’re Spanish? Or is that Mexican?” The way he said it was an insinuation. “I have business in Mexico myself.”

He said something in Spanish.

I understood, right enough. Some things sound the same in any language. I kept my face blank.

“I’ve never been to Mexico, no.”

He leered. “You’re certain? I’ve always liked the sympaticas—”

A sharp voice came from the doorway. “Harpending.”

We both turned to see Ralston. I felt relief wash through me.

His glance flicked over me, and then he turned to Harpending. “Apologize to Mrs. Smith.”

Harpending hesitated only briefly, then gave me an elegant, mocking bow. “I do beg your pardon, ma’am, if I’ve caused offense. I could no more fail to notice a beautiful woman than I would close my eyes to the beauties of nature.”

As he stepped past Ralston, I heard him say, “Settle down, Ralston. A good-looking woman is made to be looked at, otherwise, wherefore was she created?”

Ralston turned back to me. I could see he was holding his temper only with effort. “I sincerely regret the behavior of my guest.”

It was the chance I needed to win his trust. I summoned all the lightness I could muster.

“I don’t pay men any mind past their third drink.” I glanced toward the door Harpending had just exited. “Boy like that—no mind past his first… half.”

Ralston laughed, pleased. “Wise counsel from a wise woman.”

But I didn’t get much sleep that night. I had no illusions. Harpending was a snake. These Knights of the Golden Circle would have to be watched.

As soon as I could, I reported on Harpending to the Executive Committee

I took even greater care than usual getting to the AME church, where I knew they would be meeting. Suddenly everyone on the street seemed suspect.

I found J.J. Moore, Peter Anderson, and William H. Hall in the meeting room of the church. And James Madison Bell. I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised to see him already in the inner circle, but I’d been worried about getting news to him discreetly, and it was a relief that he was there.

The men were silent and tense, listening to my recounting of the scene at Ralston’s.

“The Knights of the Golden Circle,” J.J. repeated. “We’ve heard that name before.”

“Secessionists,” Anderson supplied.

“With too many military men among them,” Hall added.

“And Senator Gwin is involved, surely,” J.J. Moore said tightly.

Hall nodded. “One damn way or another. He’s never not involved.”

Anderson was skeptical. “Harpending sounds like a hotheaded boy. Are we making much of nothing?”

The jab at me could not be more clear. I kept my face still.

James frowned, and spoke thoughtfully, without looking at me. “We all know these ‘boys.’ Hotheaded—and hair-triggered. A perfect tool in the hands of a Gwin or a Terry.”

There was a muttering among the men.

I was grateful for James’ backing. And inwardly raging that I would need validation from a man to be taken seriously.

J.J. decided it. “We watch this Harpending. He’ll lead to the Knights of the Golden Circle. Spread the word.”

He turned in the room, looking at all of us. All nodded agreement. We had our spies. Of course we did. We had to.

Then he focused on me. “What about Ralston? Where does he stand?”

I hesitated. “Ralston is hard to gauge. But I have eyes on him.”

And I fully intended to have more.

Keep reading!

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Subscribe for notifications of new chapters (no more than once a month)

Mary Ellen's story certainly explains the obvious evidence in her face of her high level of constant stress. Princess Diana's face showed similar stress in at least one interview done not too too long before she died.

Shocking how very careful Black Americans in SF had to be, way back then, even before any railroad or relatively easy way to move from coast to coast. That they could be dragged back to slavers, even in a free state like CA, all the way on west coast. Intricate, careful networks of self-protection created in such a faraway place from New Orleans or anything on the east coast. Seems like it'd have been easy to go out there and get 'lost' in all that was happening as the city sprang up.