Washington, DC

Ted & Anna Judah, Senator William Gwin

After Ted’s appointment by the Railroad Convention, Ted and Anna had once again survived the long steamer journey back to Washington.

As ever, Anna felt quite breathless at the sight of the elegant, temple-like buildings, themagnitude of the Capitol—even with the Capitol building itself still unfinished, missing the top of its dome. She was reminded of Randolph’s assessment: "A city of magnificent distances."

But she found the character of the city strikingly changed since the nomination of Lincoln. Tensions crackled between North and South, Democrat and Republican, Northern Democrat and Southern Democrat—fissures that often broke out into physical violence. She was unnerved to see men wearing Secesh cockades everywhere she and Ted went. It seemed a deliberate, insolent challenge to the Republican nomination: a threat that the Union would be torn asunder if Lincoln were elected.

“Is it not treason?” she wondered, sometimes aloud.

Ted paid little mind to the hostilities. He was entirely focused on the task at hand, first compiling a pamphlet, “A Practical Plan for Building the Pacific Railroad,” and then distributing it via letters to the newspapers, pressing the leaflets into the hands of legislators. He already had valuable support from new Congressman Burch from California, whom Ted and Anna had met on the steamer journey to New York. This had been no accident: Ted had deliberately booked passage on the same ship as Burch. The Judahs had dined often with the Congressman, and one night as the three were at supper, Anna had—demurely of course—suggested the idea of a railroad exhibit, to make the abstract visual and immediate to the legislators they must win over. Burch had introduced Ted to Congressman John Logan from Illinois, who was impressed enough by the idea of an exhibit to procure Ted the use of a room in the Capitol.

And there, Judah and Anna created a Pacific Railroad Museum.

Ted collected maps, surveys, reports, anything he could purloin from national archives that would dramatize the necessity for the transcontinental railroad. The Judahs built up a panoramic display, using the charts Anna had compiled of Ted’s surveys and statistics, and the sketches and oils she had done in the Sierras to illustrate the vision.

Legislators trickled in to investigate. And one by one, the Judahs began convincing Congressmen, officials of various departments and bureaus, that the railroad was within reach.

At Anna’s urging, Ted practiced his argument and concentrated his efforts on convincing Congressmen to pass legislation funding a detailed, practical survey "on one selected route.” And as she had learned from years of experience, Anna used gentle grace and wit to temper Ted’s enthusiasm. But she found that Ted was becoming quite the salesman. His conversation on the subject of the railroad was so entertaining that few resisted his appeal. The trickle of visitors soon became a steady stream of interested politicians, as well as curious clerks and even ordinary Washington citizens. They stood in the museum surrounded by the representation of a coast-to-coast railroad, and felt inspiration catch fire.

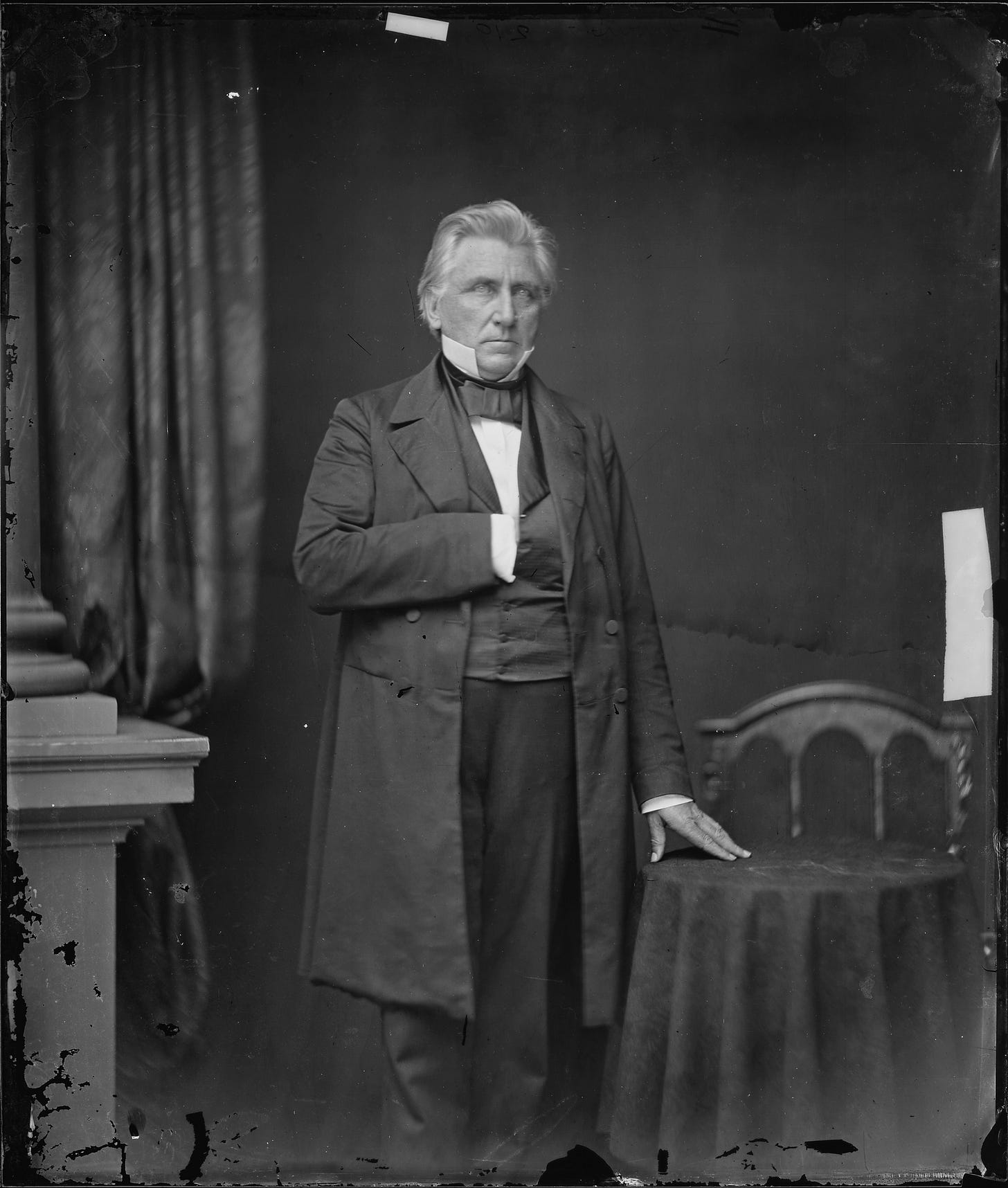

One day Ted looked up to see an imposing man standing in the doorway: in his mid-fifties, a good six feet tall, with regally graying hair and an aristocratic bearing.

Anna was first to recognize him. She stifled her dislike for his politics, reminding herself of his potential use. “Senator Gwin,” she said, and stepped toward him in cordial greeting. “We had so hoped to see you here.”

Ted felt elation bubble up inside him. The senior senator from California himself! He was a powerful voice in Congress, rumored to spend an incredible $75,000 of his own money each year in entertaining power brokers and maintaining his mansion on Nineteenth and I Street.

Gwin’s endorsement could well be the turning point in their long struggle.

The senator gave Anna a courtly bow—and then turned his attention to Ted as if she were not in the room. “So this is the young fellow who is determined to build a railroad.”

Ted beamed with pride. “On the Central Pacific Route, Senator. With terminus in California.”

Senator Gwin took a slow, thoughtful tour around the museum, asking questions about specifics. He seemed impressed by Ted’s careful estimates: the first step, the thorough survey, to cost $200,000. The final railroad, Ted believed, would cost an average of $75,000 per mile, a total of $150,000,000 from the Mississippi to the Pacific.

Of course Gwin knew the proposed route well. He pointed out the numerous people who had died on the slopes of Donner Pass, and the brutal snows that had brought a horrific end to the Donner party itself.

“Anywhere men can go by foot, they can go by rail,” Ted asserted.

Gwin stared at him a moment, then laughed. “Your confidence is as impressive as your credentials. It is our new Congressman Burch who is to present your bill next session, is it not? I shall have a word with him.”

The senator had barely stepped out the door when Ted turned and swept Anna up in jubilation. “We have done it now, Anna. With Senator Gwin on our side…”

Anna returned Ted’s embrace, but when she untangled herself and stepped back, her face was troubled. “But is he? Gwin wants a railroad badly, it is true. But he is a major slave power himself, holding more than two hundred souls in bondage. His plantation lies along the Southern rail route proposed by Jefferson Davis. That route clearly would much better serve his own politics and financial interests.”

“He is here to serve the best interests of California,” Ted said confidently. “It is his sworn duty.”

But days, then weeks went by. And Gwin had not yet spoken with Burch.

When Burch stood before Congress to propose the Railroad Bill, the chamber instantly tabled it until the new Congress reconvened after the election. Then Senator Gwin rose. Ted listened, stupefied, as Gwin proceeded to propose a completely different bill, an ostensible compromise— that instead significantly favored the Southern route advocated by Jefferson Davis.

Fortunately, Northern senators were not taken in by the sham. They wasted no time tabling Gwin’s bill.

But Ted was reeling. Anna had to bite her lips to keep from saying she had warned him.

In subsequent days, he sunk into a gloom from which she could not rouse him. Two years of work had been set aside in the time it took to make a motion.

Anna herself was finding the city unbearable. In California, isolated in the Sierras, she had been fairly sheltered from the political virulence. Here in the East she heard increasingly fervid arguments defending slavery, including, to her horror, using passages from the Bible itself.

The attacks on the Republican candidate, Lincoln, made him out to be barely human. But far worse, his name was not even to appear on the ballot in ten of the fifteen slave states. Such was the political power wielded by the plantation elite.

How is this democracy? Anna wondered.

Then one morning Ted raced into their rooms, waving a newspaper. “Look, Anna! A breakthrough—”

She took up the paper and read the bold headline announcing commencement of the Pony Express.

The freighting firm of Russell, Majors and Waddell had hired eighty young riders, average age just eighteen, to carry the mail across the continent on fleet-footed ponies. They carried leather pouches filled with twenty pounds of mail wrapped in oiled silk to keep out the moisture, and revolvers and knives to defend themselves against wolves and mountain lions. The riders donned close-fitting clothes to reduce wind resistance and the horses wore light racing saddles.

The intrepid young riders sped across the continent at an unheard-of twenty-five miles per hour, stopping every ten to fifteen miles for a fresh horse at one of the hundreds of relay stations along the way. As the rider approached each station, his replacement mount would be saddled and ready to go. The rider would transfer his mail pouch and be on his way again in less than two minutes.

The article concluded, “making the delivery of mail from New York to California possible in a ride of—”

“Just ten days’ time!” Ted finished. “And the route, Anna!”

She said it with him: “Via the California-Mormon Trail.”

It was an amazing boon. All of the attention of the newspapers and the enthusiasm of the country was suddenly focused on the very route Ted was advocating for the railroad.

“Gwin shall not have his way,” Ted declared. “The success of the Pony Express will convince investors to fund a survey. And if Lincoln is elected, if he brings a Republican victory to the House of Representatives as well, the Republican commitment to a transcontinental railroad could push a real railroad bill through the Senate.”

If. Could. If. Anna thought. But she voiced no objection. It only mattered that Ted was back to his old self.

He paced, declaiming. “The task is clear: to find the precise route, form a corporation to commission a thorough survey, and do it in time to present to the new President and Congress in January.”

“I do not know if I am married to a man or a railroad,” she teased.

He turned to her with that familiar look in his eyes. “We set sail for California immediately.”

Anna smiled—and went to find a suitcase.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Your story restores my hopes, pride, deep love, and appreciation for this country, Alexandra!! So valuable to bring the true history of our country to life as most of us have never read, seen or heard. Did we discuss what a fabulous film or better yet, series, this story would also make?? Helpful to know that some of the same ridiculous political dynamics of today... are really not new at all. Whew!! So exciting!!