There were only three routes to California. Only 40,000 of the estimated 90,000 “Forty-Niners” who attempted them ever reached San Francisco.

A fifth of those who did make it were dead within six months.

1. The Overland Route

To enjoy such a trip … a man must be able to endure heat like a Salamander, mud and water like a muskrat, dust like a toad, and labor like a jackass. He must learn to eat with his unwashed fingers, drink out of the same vessel as his mules, sleep on the ground when it rains, share his blanket with vermin, and have patience with mosquitos. He must cease to think, except of where he may find grass and water and a good camping place. It is hardship without glory.”

— Anonymous settler, in the St. Joseph, Missouri Gazette

The dearth of water is fearful. Although the whole region is deeply seamed and gullied by water-courses—now dry, but in rainy weather mill-streams—no springs burst from their steep sides. We have not passed a drop of living water in all our morning’s ride, and but a few pailfuls of muddy moisture at the bottoms of a very few of the fast-drying sloughs or sunken holes in the beds of dried-up creeks. Yet there has been much rain here this season, some of it not long ago. But this is a region of sterility and thirst. If utterly unfed, the grass of a season would hardly suffice, when dry, to nourish a prairie-fire.

— Horace Greeley

Morning comes, and the light of day presents a scene more horrid than the route of a defeated army; dead stock line the roads, wagons, rifles, tents, clothes, everything but food may be found scattered along the road; here an ox, who standing famished against a wagon bed until nature could do no more, settled back into it and dies; and there a horse kicking out his last gasp in the burning sand, men scattered among the plain and stretched out among the dead like corpses.

— Eleazer Stillman Ingalls: Journal of a Trip to California by the Overland Route Across the Plains in 1850-51

Wednesday 11 - seen 3 graves

Thursday 12 - seen 6 graves

Friday 13 - Passed the big Simahaw and Seen 5 graves

Saturday 14 - Seen 11 graves And came in the[- - - - - ]Territory

Sunday 15 - Crossed big 150[- - - ]Blue and so Seen 7 graves joes

Saturday 16 - Seen no graves crossed Cotton wood Branch

Monday 17 - Seen 2 graves and had to he[- - - ]frost[- -]s m[- - - - ]

- Journal of Ezekial B. Headley

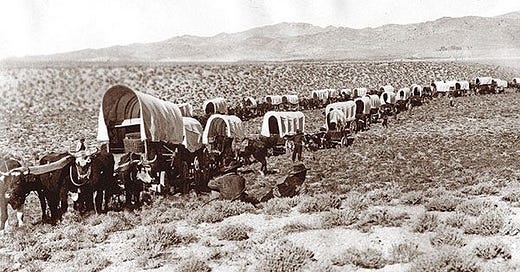

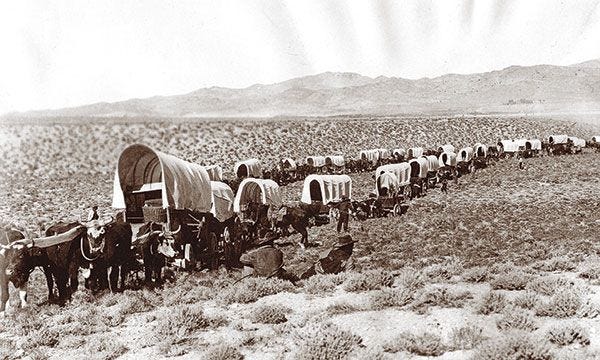

The Overland Route was five or six months minimum by wagon, mules or oxen. It meant first traveling to St. Louis or other departure points along the Missouri River and waiting until spring to depart. From there the wagon trails meandered three thousand miles across the western half of the North American continent to California, a journey of deadly geographic obstacles: river crossings, the Forty Mile Desert, the sheer cliffs of the Wasatch Range and the Sierras. It had to be carefully timed to avoid the winter in the mountains and the worst of spring flooding on the plains. On a good day the pace of travel was two miles.

Pioneers were drowned while crossing swollen rivers. They were crushed by wagon wheels and trampled by their own animals. They were killed by accidental discharge of their own and other pioneers’ firearms. They died of thirst on the deserts and of scurvy and cholera and typhoid and sheer exhaustion everywhere else.

2. Around the Horn

“Below 40 South there is no law. Below 50 South there is no God.”

— A sailor’s adage

A fresh wind was blowing in the morning when I rose, and a thick fall of snow nearly blinded me as I went out on the deck. The cold had become intense, and it was a time of suffering for the poor sailors. The men had scarcely got the fore and maintop sail set when the storm came on again with a fury far exceeding anything we had yet encountered and they were again sent aloft to furl the sails. We now lay to under two stay sails, the ship rolling with great violence, and the seas breaking over the decks… The waves rolled up into immense billows covered with foam and dashed against the sides of the ship and over the bulwarks, deluging every person and setting afloat every loose thing upon the decks. Borne about by the raging waters, the ship often staggered for a moment upon the crest of a great wave, as if fearful of the plunge she was about to take, but quickly sinking down into the moving chasm, as if she were attempting to dive to the bottom of the sea, until overtaken by another billow, she rose to its crest, though only to be sunk into another then another gulf. The interposition of a merciful Providence only could save us.

— Joseph Lamson, Round Cape Horn

The cheapest route was the sea voyage around Cape Horn, at the very bottom of South America an all-water route through the notorious Strait of Magellan. The trip from New York to San Francisco by square-rigger or steamer was fourteen thousand miles and took four to six months.

In addition to shipboard illnesses like cholera, smallpox, typhoid, and scurvy, the traveler could look forward to gale-force winds that blew sails and rigging to pieces, extremes of weather from freezing snow and hail to becalmed days of unbearable heat—and the constant possibility of being washed overboard by the seventy to eighty-foot waves. Men not infrequently succumbed to the tedium and uncertainty, lost their senses and had to be chained in the hold.

3. The Central America Route

The third, shortest, and most expensive route to California was the Central American Route, via Nicaragua or Panama.

Charles Warren Stoddard (Age 12)

Rochester, NY to San Juan del Norte, Nicaragua

Crossing Panama Via the Chagres River, Charles Christian Nahl (Public domain)3

We children had been watching and waiting for it. The house had been stripped bare; many cases of goods were awaiting shipment around Cape Horn to California. California! A land of fable! We knew well enough that our father was there, and had been for two years or more; and that we were at last to go to him, and dwell there with the fabulous in a new home more or less fabulous,—yet we felt that it must be altogether lovely. We said good-bye to everybody,—getting friends and fellow-citizens more or less mixed as the hour of departure from our native city drew near. We were very much hugged and very much kissed and not a little cried over; and then at last, in a half, dazed condition, we left Rochester, New York, for New York city, on our way to San Francisco by the Nicaragua route. This was 1855, when San Francisco, it may be said, was only six years old.

There is no change like a sea change, no matter who suffers it; and one's first sea voyage is a revelation. The mystery of it is usually not unmixed with misery. It was a very serious undertaking to uproot one's self, say good-bye to all that was nearest and dearest, and go down beyond the horizon in an ill-smelling, overcrowded, side-wheeled tub. Not a soul on the dock that day but fully realized this. The dock and the deck ran rivers of tears, it seemed to me; and when, after the lingering agony of farewells had reached the climax, and the shore-lines were cast off, and the Star of the West swung out into the stream, with great side-wheels fitfully revolving, a shriek rent the air and froze my young blood. Some mother parting from a son who was on board our vessel, no longer able to restrain her emotion, was borne away, frantically raving in the delirium of grief. I imagined my heart was about to break; and when we put out to sea in a damp and dreary drizzle, and the shore-line dissolved away, while on board there was overcrowding, and confusion worse confounded in evidence everywhere,—perhaps it did break, that overwrought heart of mine and has been a patched thing ever since.

We were a miserable lot that night, pitched to and fro and rolled from side to side as if we were so much baggage. And there was a special horror in the darkness, as well as in the wind that hissed through the rigging, and in the waves that rushed past us, sheeted with foam that faded ghostlike as we watched it,—faded ghostlike, leaving the blackness of darkness to enfold us and swallow us up.

Day after day for a dozen days we ploughed that restless sea. There were days into which the sun shone not; when everybody and everything was sticky with salty distillations; when half the passengers were sea-sick and the other half sick of the sea. The decks were slimy, the cabins stuffy and foul. The hours hung heavily, and the horizon line closed in about us a gray wall of mist.

Then I used to bury myself in my books and try to forget the world, now lost to sight, and, as I sometimes feared, never to be found again. I had brought my private library with me; it was complete in two volumes. There was "Rollo Crossing the Atlantic," by dear old Jacob Abbot; this book of juvenile travel and adventure I read on the spot, as it were. The other volume was a pocket copy of "Robinson Crusoe," upon the fly-leaf of which was scrawled, in an untutored hand, "Charley from Freddy,"—this Freddy was my juvenile chum. I still have that little treasure, with its inscription undimmed by time. Frequently I have thought that the reading of this charming book may have been the predominating influence in the development of my taste and temper.

We weathered Cape Sable and the Florida Keys. No sky was ever more marvellously blue than the sea beneath us. The density and the darkness that prevail in Northern waters had gone out of it; the sun gilded it, the moon silvered it, and the great stars dropped their pearl-plummets into it in the vain search for soundings.

Sea gardens were there,—floating gardens adrift in the tropic gale; pale green gardens of berry and leaf and long meandering vine, rocking upon the waves that lapped the shores of the Antilles, feeding the current of the warm Gulf Stream; and, forsooth, some of them to find their way at last into the mazes of that mysterious, mighty, menacing sargasso sea. Strange sea-monsters, more beautiful than monstrous, sported in the foam about our prow, and at intervals dashed it with color like animated rainbows. From wave to wave the flying fish skimmed like winged arrows of silver. Sometimes a land-bird was blown across the sky—the sea-birds we had always with us,—and ever the air was spicy and the breeze like a breath of balm.

One day a little cloud dawned upon our horizon. It was at first pale and pearly, then pink like the hollow of a sea-shell, then misty blue,—a darker blue, a deep blue dissolving into green, and the green outlining itself in emerald, with many a shade of lighter or darker green fretting its surface, throwing cliff and crest into high relief, and hinting at misty and mysterious vales, as fair as fathomless. It floated up like a cloud from the nether world, and was at first without form and void, even as its fellows were; but as we drew nearer—for we were steaming toward it across a sea of sapphire,—it brooded upon the face of the water, while the clouds that had hung about it were scattered and wafted away.

Thus was an island born to us of sea and sky,—an island whose peak was sky-kissed, whose vales were overshadowed by festoons of vapor, whose heights were tipped with sunshine, and along whose shore the sea sang softly, and the creaming breakers wreathed themselves, flashed like snow-drifts, vanished and flashed again. The sea danced and sparkled; the air quivered with vibrant light. Along the border of that island the palm-trees towered and reeled, and all its gardens breathed perfume such as I had never known or dreamed of.

For a few hours only we basked in its beauty, rejoiced in it, gloried in it; and then we passed it by. Even as it had risen from the sea it returned into its bosom and was seen no more.

From that hour we scoured the sea for islands: from dawn to dark we were on the watch. The Caribbean Sea is well stocked with them. We were threading our way among them, and might any day hear the glad cry of "Land ho!" But we heard it not until the morning of the eleventh day out from New York. The sea seemed more lonesome than ever when we lost our, island; the monotony of our life was almost unbroken. We began to feel as prisoners must feel whose time is near out. Oh, how the hours lagged!—but deliverance was at hand. At last we gave a glad shout, for the land was ours again; we were to disembark in the course of a few hours, and all was bustle and confusion until we dropped anchor off the Mosquito Shore.

The shallowing sea was of the color of amber; the land so low and level that the foliage which covered it seemed to be rooted in the water. We dropped anchor in the mouth of the San Juan River. On our right lay the little Spanish village of San Juan del Norte; its five hundred inhabitants may have been wading through its one street at that moment, for aught we know; the place seemed to be knee-deep in water. On our left was a long strip of land—the depot and coaling station of the Vanderbilt Steamship Company.

It did not appear to be much, that sandspit known as Punta Arenas, with its row of sheds at the water's edge, and its scattering shrubs tossing in the wind.

While we were speculating as to the nature of our next experience, suddenly a stern-wheel, flat-bottom boat backed up alongside of the Star of the West. If the Star of the West was small, this stern-wheel scow was infinitely smaller. There was but one cabin, and it was rendered insufferably hot by the boilers that were set in the middle of it. There was one flush deck, with an awning stretched above it that extended nearly to the prow of the boat. It was said our passenger list numbered fourteen hundred. The gold boom in California was still at fever heat. Every craft that set sail for the Isthmus by the Nicaragua or Panama route, or by the weary route around Cape Horn, was packed full of gold-seekers. It was the Golden Age of the Argonauts; and, if my memory serves me well, there were no reserved seats worth the price thereof.

The first river boat at our disposal was for the exclusive accommodation of the cabin passengers, or as many of them as could be crowded upon her—and we were among them. Other steamers were to follow as soon as practicable. Hours, even days, passed by, and the passengers on the ocean steamers were sometimes kept waiting the arrival of the river boats that were aground or had been belated up the stream.

About two hundred of us boarded the first boat. Our luggage of the larger sort was stowed away in barges and towed after us. The decks were strewn with hand-bags, camp-stools, bundles, and rolls of rugs. The lower deck was two feet above the water. As we looked back upon the Star of the West, waving a glad farewell to the ship that had brought us more than two thousand miles across the sea, she loomed like a Noah's Ark above the flood, and we were quite proud of her—but not sorry to say good-bye.

And now away, into the very heart of a Central American forest! And hail to the new life that lay all before us in El Dorado!

The Central American Route:

The Panama Passage

Adolph Sutro (25)

Twenty-five-year old Adolph Sutro had also chosen the Central American Route, but via the Panama Passage. The first leg of the journey, by the steamship Cherokee from New York to the primitive port of Chagres, was nearly completed. Adolph would then commence the overland portion of the trip: forty miles by canoe up the Chagres River to Cruces, another mountainous twenty miles by mule or donkey to Panama City, and then negotiating for a place on a steamship for the final leg up the Pacific coast to San Francisco.

It had already been a seemingly endless journey. Not just this sea journey from Baltimore—he’d already accomplished the Atlantic crossing from Europe.

Adolph had grown up in the Rhine Province, Prussia, the eldest of eleven children. As a child he’d worked in his father’s cloth factory; as a teenager he and his brother Sali had taken over the mill when their father died. But the 1848 revolutions had brought on a wave of Jewish persecution, which intensified in subsequent years, forcing a mass emigration. The Sutro family sold the mill and booked passage to America, hoping for a fresh start in a less hostile land.

Sali had gone ahead to set up a retail store in Baltimore. But when the rest of the Sutro family set foot off the steamer in Baltimore onto the bustling dock, Adolph had been swept up in the palpable excitement of the miners departing the harbor on ships for San Francisco. If a fresh start could be made anywhere, he reasoned, it would be in that new state with such limitless possibilities. He convinced his mother that the crates of supplies they had brought for Sali’s store would sell far better in gold country.

The first available ship from New York would not depart for Panama for nearly two months. Adolph used the time to inquire into lodging and available employment in San Francisco. He learned of the Eureka Benevolent Society, a charitable organization which provided aid to Jewish immigrants, and wrote to the founder, August Helbing. Helbing wrote back, offered him work and lodging in Helbing’s own dry goods store.

Adolph set out on the sea journey with his trunks full of supplies on the Cherokee, a 210-foot-long by 35-foot-wide wooden hull steamship with side paddlewheels.

To record the journey for his mother, he’d been keeping a journal. Now, sailing into Panama, he enthused on paper about the tropical trees, the birds with their brilliantly colored plumage. “All this makes the place very romantic and interesting.”

The landing at the village of Chagres was considerably less romantic, with its miserable bamboo huts on one side of the river and not much larger huts on the other, absurdly calling themselves “Washington Hotel” and “Astor House.”

Chagres: A fifty-hut cesspool of matted reeds thatched with palm leaves, housing naked natives. More than two thousand gold-mad men were demanding transportation—canoes went to the highest bidder.

Pigs, chickens, etc., were running amid the humans, and for food, there was only fruit. The natives are very lazy and passionately fond of smoking, especially the women. Nearly every girl has a cigar in her mouth or sticks it behind her ear like a pen. Men and women are clad from the hips down or not at all, and have no shame. Some women are dressed in fine light-colored materials, with coal-black hair, decked in pearls and gold.

The white men last only a few years; the chief cause of the unhealthiness is the thick fog, laden with moisture and malaria, which rises every night from the ground. A single night’s exposure may ruin one’s health forever. Four nights were spent in this suffocating fog. We were saved from the fever only by the regular dose of quinine given us by the ship’s doctor.

The port was so notoriously unhealthy that Adolph’s life insurance policy contained a clause stating that if he remained there more than one night, his policy would be void. But finally, long past the expiration date of his insurance coverage, Adolph obtained a canoe.

We packed all our goods in the canoe and started at 1 p.m. The river is rapid, with strong eddies, dangerous in a dugout. Luxurious tropical vegetation with coconut trees, palms, bananas, oranges, citrus, wild fig, mangoes, guavas, and other often colossal trees. Thick green bamboos, sugar cane, tule, house-high grasses, cactuses, and leaves as long as a man and several feet in width. Then the climbers and parasites which grow to the top and grow down, intertwining in a thousand ways, making an impenetrable smothering foliage. There are thousands of parrots, always in pairs, pelicans, wild ducks, hundreds of hummingbirds, eagles, and vultures. In the grass, you see large lizards, chameleons, iguanas, and in the air fly large colorful butterflies. In the river are the much-dreaded alligators. The river makes many sharp, unexpected turns. By 7 p.m. we had covered about 8 miles and stopped at a native village, Catten. So far, we were delighted and excited, and had feasted on provisions from the ship.”

Travel on the Chagres continued for two days. The canoe journey grew perilous, the boats often barely avoiding logs and in constant danger of capsizing.

Four Frenchmen were upset today, but all were saved. Last week fourteen Americans were drowned. Next day, Thursday the 24th, at 3 o’clock, we reached Gorgona, where we finally had some warm food. The road from here to Panama City is virtually impassable because of the mud. We finally persuaded our boatman to go on to Cruces, seven miles further, the worst part of the river. This was really dangerous in the dark, and we were thankful for the boatman’s skill.

Charlie Stoddard

San Juan River

The river was as yellow as saffron; its shores were hidden in a dense growth of underbrush that trailed its boughs in the water, and rose, a wall of verdure, far above our smokestacks. As we ascended the stream the forest deepened; the trees grew taller and taller; wide-spreading branches hung over us; gigantic vines clambered everywhere and made huge hammocks of themselves; they bridged the bayous, and made dark leafy caverns wherein the shadows were forbidding; for the sunshine seemed never to have penetrated them, and they were the haunts of weirdness and mystery profound.

Sometimes a tree that had fallen into the water and lay at a convenient angle by the shore afforded the alligator a comfortable couch for his sun-bath. Shall I ever forget the excitement occasioned by the discovery of our first alligator! Not the ancient and honorable crocodile of the Nile was ever greeted with greater enthusiasm; yet our sportsmen had very little respect for him, and his sleep was disturbed by a shower of bullets that spattered upon his hoary scales as harmlessly as rain.

Though the alligator punctuated every adventurous hour of that memorable voyage in Nicaragua, we children were more interested in our Darwinian friends, the monkeys. They were of all shades and shapes and sizes; they descended in troops among the trees by the river side; they called to us and beckoned us shoreward; they cried to us, they laughed at us; they reached out their bony arms, and stretched wide their slim, cold hands to us, as if they would pluck us as we passed. We exchanged compliments and clubs in a sham-battle that was immensely diverting; we returned the missiles they threw at us as long as the ammunition held out, but captured none of the enemy, nor did the slightest damage—as far as we could ascertain.

Often the parrots squalled at us, but their vocabulary was limited; for they were untaught of men. Sometimes the magnificent macaw flew over us, with its scarlet plumage flickering like flame. Oh, but those gorgeous birds were splashes of splendid color in the intense green of that tropical background!

There were some natives here—Indians probably,—with dark skins bared from head to foot; they wore only the breech-clout, and this of the briefest. Evidently they were children of Nature.

We were always wondering where these gentle savages lived and how they escaped with their lives from the thousand and one pests that haunted the forest and lay in wait for them. Every biting and stinging thing was there. The mosquitoes nearly devoured us, especially at night; while serpents, scorpions, centipedes, possessed the jungle. There also was the lair of larger game. It is said that sharks will pick a white man out of a crowd of dark ones in the sea; not that he is a more tempting and toothsome morsel—drenched with nicotine, he may indeed be less appetizing than his dark-skinned, fruit-fed fellow,—but his silvery skin is a good sea-mark, as the shark has often confirmed. So these dark ones in the semi-darkness of the wood may, perhaps, pass with impunity where a pale-face would fall an easy prey.

Adolph Sutro

Cruces

We had imagined Cruces was a real town, with good places to sleep, but we were again disappointed. At the United States Hotel, 300 people were crowded in. Supper of coffee, bread, and already tainted meat cost one dollar. I was glad to be in the closed house after 4½ days on the river. The large sleeping room had about 150 cots, crowded and stacked, with no bedding at all. But I had a good night’s rest anyhow.

It is impossible to describe the journey from Cruces to Panama City. At every step, you are in danger of being thrown. Many seasoned travelers, who have crossed the Cordilleras and the Alps, told me that this was the worst trail in the world. Ten minutes after we started, the mules sank down to their bellies in the mud. I thought I would never get out again. The path cut through roots and was often so narrow that the mules barely scraped through and were unable to find their feet. We crossed creeks and swamps and got covered totally with mud. At night the mosquitoes were as big as grasshoppers and alligators were all around.

Then there was the dread of robbers. The night before we left, a young man was murdered and robbed of $9,000. Finally, by evening, we reached a native hut to spend the night. I shall never forget this night. At dark, my traveling companions left me, and I stayed to guard my baggage, alone with the muleteers who spoke only Spanish. I was armed but quite frightened. At the nearby open hut were about 150 men returning from California, who looked like highwaymen. I had had no food all day, then found a man who sold me a piece of bread for a shilling. It had rained all day, and I was again totally soaked with no possible clothing change. At last I lay on the ground among these ruffians, but sleep was impossible. Next morning there was nothing to eat.

Not only that, but Adolph discover his riding mule had been stolen during the night. The mules remained to transport his baggage, but Adolph was forced to go on foot, potentially for seven miles.

In a half hour I was so exhausted I could hardly move a step. The heat was insufferable. Finally, a man let me ride his mule for a few dollars. By 9 a.m. I was overjoyed to see my first sight of Panama City and the Pacific.

The old Spanish town was mostly in ruins. He found shelter in the American “Hotel.”

In my room are six beds; some have fifty, stacked three or four high. I eat scarcely anything but bread and a cup of tea; the meats all smell. You won’t believe the terrible inconvenience; in all Panama City, there is no water closet. Everyone must go on the walls of the city, even if you are unwell in the night. The natives live on yams, bananas, and coconuts. There is no agriculture and no vegetables. The natives are all Catholics, so there are lots of priests and church bells. The soldiers are truly ridiculous, black, white and yellow all mixed up, none with shoes.

Adolph spent six days in the “American Hotel” before he was finally able to board the California, a steamship to San Francisco. But he considered himself lucky: he’d heard many tales of pioneers being stranded for months waiting for passage. He was also able to purchase a cabin, which was unbelievable luxury after the grueling jungle journey. He shut the door behind him and dropped onto the narrow bunk in relief and bliss.

Just one more leg to go.

Charlie Stoddard

Lake Nicaragua to the California Coast

We were nearing the end of the journey across the Isthmus and were shortly to embark for San Francisco. I fear we children regretted the fact. Our life for three days had been like a veritable "Jungle Book." It almost out-Kiplinged Kipling. We might never again float through Monkey Land, with clouds of parrots hovering over us and a whole menagerie of extraordinary creatures making side-shows of themselves on every hand.

Yonder, in the offing, the ship that was to carry us northward to San Francisco lay at anchor. We had passed from sea to sea, a distance of about two hundred miles.

And so we left the land of the lizard. What wonders they are! From an inch to two feet in length, slim, slippery, and of many and changeful colors, they literally inhabit the land, and are as much at home in a house as out of it; indeed, the houses are never free of them. They sailed up the river with us, and crossed the lake in our company, and sat by the mountain wayside awaiting our arrival; for they are curious and sociable little beasts. As for the San Juan river, 'tis like the Ocklawaha of Florida many times multiplied, and with all its original attractions in a state of perfect preservation.

All the way up the coast we literally hugged the shore; only during the hours when we were crossing the yawning mouth of the Gulf of California were we for a single moment out of sight of land. I know not if this was a saving in time and distance, and therefore a saving in fuel and provender; or if our ship, the John L. Stevens, was thought to be overloaded and unsafe, and was kept within easy reach of shore for fear of accident. We steamed for two weeks between a landscape and a seascape that afforded constant diversion. At night we sometimes saw flame-tipped volcanoes; there was ever the undulating outline of the Sierra Nevada Mountains through Central America, Mexico, and California.

There was Santa Catalina, off the California coast, then an uninhabited island given over to sunshine and wild goats, now one of the most popular and populous of California summer and winter resorts—for 'tis all the same on the Pacific coast; one season is damper than the other, that is the only difference. The coast grew bare and bleak; the wind freshened and we were glad to put on our wraps. And then at last, after a journey of nearly five thousand miles, we slowed up in a fog so dense it dripped from the scuppers of the ship; we heard the boom of the surf pounding upon the invisible shore, and the hoarse bark of a chorus of sea-lions, and were told we were at the threshold of the Golden Gate, and should enter it as soon as the fog lifted and made room for us.

We were buried alive in fathomless depths of fog. We were a fixture until that fog lifted. It was an impenetrable barrier. Upon the point of entering one of the most wonderful harbors in the world, the glory of the newest of new lands, we found ourselves prisoners, and for a time at least involved in the mazes of ancient history.

At last the fog began to show signs of life and motion. Huge masses of opaque mist, that had shut us in like walls of alabaster, were rent asunder and noiselessly rolled away. The change was magical. In a few moments we found ourselves under a cloudless sky, upon a sparkling sea, flooded with sunshine, and the Golden Gate wide open to give us welcome.

The statistics! It really does give more meaning to "e pluribus unum." That less than half made the journey alive.

Stoddard was such a descriptive and fun writer. Sutro became mayor of sf and, with Joaquin and Ina, established Arbor Day and planted some 4 million trees in the bay area. It really is hard to imagine the hardship of getting here now. Vivid research, really brings it to light.