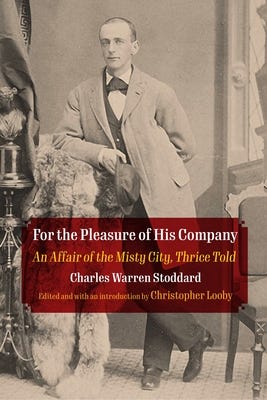

San Francisco poet and journalist Charles Warren Stoddard (1843-1909) wrote the first acknowledged American novel about openly gay characters (The Pleasure of His Company, 1903), and long before that, lived out in a time that had not yet heard the word homosexual.

To me, he’s an obvious founding father of San Francisco’s vibrant, vital and beloved gay community.

His friends were the creme de la creme of Bohemian San Francisco: Mark Twain, Ina Coolbrith, Bret Harte, Ambrose Bierce, Ada Clare, Adah Isaacs Menken. He wrote for all the best California journals and newspapers: The Golden Era, The Overland Monthly, the San Francisco Chronicle (owned and operated by his old schoolmate, the volatile Charles de Young).

Charlie, Bret Harte and Ina Coolbrith were such great friends and collaborators they were known as “The Overland Trinity.”

Though Charlie at first kept his longings to himself, he soon grew bolder in private and public life. His friends and colleagues all knew he loved men. They were not simply tolerant but protective of him.

He began his writing career as a teenage poet, and soon became one of California’s best and best-known. But he really found his niche as a travel writer—no ordinary travel writer, but one who daringly chronicled his affairs with young native men in Hawaii and the South Seas.

Some San Francisco readers probably didn’t quite grasp the extent of these relationships—others knew full well. But amazingly for the time, no one ever complained.

Charlie came out to Bret Harte and Ina Coolbrith in his first of those stories, Chumming with a Savage, excerpted in the chapter below.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Chapter 193

July 1869 —San Francisco, California

Charles Warren Stoddard (26), Bret Harte (33), Ina Coolbrith (28)

That summer, Charlie Stoddard returned to California, after six months in the islands. He was tanned, fit, and physically fulfilled for the first time in his life.

He dropped in to the Overland offices when he was sure Ina would be away teaching at the language school; he was not ready to face her perceptive gaze. He was surprised to learn from Hattie that Frank Harte had abruptly given up his position at the Mint and that the Hartes had moved residence across the Bay to the village of San Rafael.

It meant Charlie would have to wait longer than he’d anticipated for a response to his latest submission. He knew it was the best piece he’d ever written. It was also the most honest. And Charlie was more than anxious about what response he would get.

He was terrified.

Because the story was a detailed, unsparing account of his time in the islands. And he found he could no more repress his writing than he could suppress his feelings.

Chumming with a Savage

Fate, or the Doctor, or something else, brought me first to this loveliest of valleys, so shut out from everything but itself that there were no temptations which might not be satisfied.

Well! here, as I was looking about at the singular loveliness of the place,—you know this was my first glimpse of its abrupt walls, hung with tapestries of fern and clambering convolvulus; at one end two exquisite waterfalls, rivalling one another in whiteness and airiness, at the other the sea, the real South Sea, breaking and foaming over a genuine reef, and even rippling the placid current of the river that slipped quietly down to its embracing tide from the deep basins at these waterfalls,—right in the midst of all this, before I had been ten minutes in the valley, I thought I saw something white there, something white and fluttering, moving about.

I knew pretty well what it was, and didn't go after it on an uncertainty.

I saw a straw hat, bound with wreaths of fern and maile; under it a snow-white garment, rather short all around, low in the neck, and with no sleeves whatever. There was no sex to that garment; it was the spontaneous offspring of a scant material and a large necessity. I'd seen plenty of that sort of thing, but never upon a model like this, so entirely tropical,—almost Oriental. As this singular phenomenon made directly for me, and, having come within reach, there stopped and stayed, I asked its name, using one of my seven stock phrases for the purpose; I found it was called Kána-aná.

Down it went into my note-book; for I knew I was to have an experience with this young scion of a race of chiefs. Sure enough, I have had it. He continued to regard me steadily, without embarrassment. He seated himself before me; I felt myself at the mercy of one whose calm analysis was questioning every motive of my soul. This sage inquirer was, perhaps, sixteen years of age. His eye was so earnest and so honest, I could return his look. I saw a round, full, rather girlish face; lips ripe and expressive, not quite so sensual as those of most of his race; not a bad nose, by any means; eyes perfectly glorious,—regular almonds,—with the mythical lashes "that sweep," etc., etc. The smile which presently transfigured his face was of the nature that flatters you into submission against your will.

Having weighed me in his balance,—and you may be sure his instincts didn't cheat him; they don't do that sort of thing,—he placed his two hands on my two knees, and declared I was his best friend, as he was mine; I must come at once to his house, and there live always with him. What could I do but go? He pointed me to his lodge across the river, saying, There was his home and mine.

Thereupon I renounced all the follies of this world, actually hating civilization, and feeling entirely above the formalities of society. I resolved on the spot to be a barbarian, and, perhaps, dwell for ever and ever in this secluded spot.

So Kána-aná brought up his horse, got me on to it in some way or other, and mounted behind me to pilot the animal and sustain me in my first bareback act. Over the sand we went, and through the river to his hut, where I was taken in, fed, and petted in every possible way, and finally put to bed, where Kána-aná monopolized me, growling in true savage fashion if any one came near me.

I didn't sleep much, after all. I think I must have been excited. I thought how strangely I was situated: alone in a wilderness, among barbarians; my bosom friend, who was hugging me like a young bear, not able to speak one syllable of English, and I very shaky on a few bad phrases in his tongue. We two lay upon an enormous old-fashioned bed with high posts,—very high they seemed to me in the dim rushlight. The natives always burn a small light after dark; some superstition or other prompts it. The bed, well stocked with pillows, or cushions, of various sizes, covered with bright-colored chintz, was hung about with numerous shawls, so that I might be dreadfully modest behind them. It was quite a grand affair, gotten up expressly for my benefit.

The rest of the house—all in one room, as usual—was covered with mats, on which various recumbent forms and several individual snores betrayed the proximity of Kána-aná's relatives. How queer the whole atmosphere of the place was! The heavy beams of the house were of some rare wood, which, being polished, looked like colossal sticks of peanut candy. Slender canes were bound across this framework, and the soft, dried grass of the meadows was braided over it,—all completing our tenement, and making it as fresh and sweet as new-mown hay.

The natives have a passion for perfumes. Little bunches of sweet-smelling herbs hung in the peak of the roof, and wreaths of fragrant berries were strung in various parts of the house. I found our bedposts festooned with them in the morning.

O, that bed! It might have come from England in the Elizabethan era and been wrecked off the coast; hence the mystery of its presence. It was big enough for a Mormon. There was a little opening in the room opposite our bed; you might call it a window, I suppose. The sun, shining through it, made our tent of shawls perfectly gorgeous in crimson light, barred and starred with gold. I lifted our bed-curtain, and watched the rocks through this window,—the shining rocks, with the sea leaping above them in the sun. There were cocoa-palms so slender they seemed to cast no shadow, while their fringed leaves glistened like frost-work as the sun glanced over them. A bit of cliff, also, remote and misty, running far into the sea, was just visible from my pyramid of pillows. I wondered what more I could ask for to delight the eye. Kána-aná was still asleep, but he never let loose his hold on me, as though he feared his pale-faced friend would fade away from him. He lay close by me. His sleek figure, supple and graceful in repose, was the embodiment of free, untrammelled youth. You who are brought up under cover know nothing of its luxuriousness. How I longed to take him over the sea with me, and show him something of life as we find it. Thinking upon it, I dropped off into one of those delicious morning naps.

I awoke again presently; my companion-in-arms was the occasion this time. He had awakened, stolen softly away, resumed his single garment,—said garment and all others he considered superfluous after dark,—and had prepared for me, with his own hands, a breakfast, which he now declared to me, in violent and suggestive pantomime, was all ready to be eaten. It was not a bad bill of fare,—fresh fish, taro, poe, and goat's milk. I ate as well as I could, under the circumstances. I found that Robinson Crusoe must have had some tedious rehearsals before he acquired that perfect resignation to Providence which delights us in book form. There was a veritable and most unexpected table-cloth for me alone. I do not presume to question the nature of its miraculous appearance. Dishes there were—dishes, if you're not particular as to shape or completeness; forks, with a prong or two—a bent and abbreviated prong or two; knives that had survived their handles; and one solitary spoon. All these were tributes of the too generous people, who, for the first time in their lives, were at the inconvenience of entertaining a distinguished stranger. Hence this reckless display of tableware. I ate as well as I could, but surely not enough to satisfy my crony; for, when I had finished eating, he sat about two hours in deep and depressing silence, at the expiration of which time he suddenly darted off on his bareback steed and was gone till dark, when he returned with a fat mutton slung over his animal. Now, mutton doesn't grow wild thereabout, neither were his relatives shepherds; consequently, in eating, I asked no questions for conscience' sake.

The series of entertainments offered me were such as the little valley had not known for years: canoe-rides up and down the winding stream; bathings in the sea and in the river, and in every possible bit of water, at all possible hours; expeditions into the recesses of the mountains, to the waterfalls that plunged into cool basins of fern and cresses, and to the orange grove through acres and acres of guava orchards; some climbings up the precipices; goat hunting, once or twice, as far as a solitary cavern, said to be haunted,—these tramps always by daylight; then a new course of bathings and sailings, interspersed with monotonous singing and occasional smokes under the eaves of the hut at evening.

If it is a question how long a man may withstand the seductions of nature, and the consolations and conveniences of the state of nature, I have solved it in one case; for I was as natural as possible in about three days. I wonder if I was growing to feel more at home, or more hungry, that I found an appetite at last equal to any table that was offered me! Chicken was added to my already bountiful rations, nicely cooked by being swathed in a broad, succulent leaf, and roasted or steeped in hot ashes. I ate it with my fingers, using the leaf for a platter. Almost every day something new was offered at the door for my edification. Now, a net full of large guavas or mangoes, or a sack of leaves crammed with most delicious oranges from the mountains, that seemed to have absorbed the very dew of heaven, they were so fresh and sweet. Immense lemons perfumed the house, waiting to make me a capital drink. Those superb citrons, with their rough, golden crusts, refreshed me. Cocoa-nuts were heaped at the door; and yams, grown miles away, were sent for, so that I might be satisfied. Eat I must, at all hours and in all places; and eat, moreover, before he would touch a mouthful. So Nature teaches her children a hospitality which all the arts of the capital cannot affect.

I wonder what it was that finally made me restless and eager to see new faces! Perhaps my unhappy disposition, that urged me thither, and then lured me back to the pride of life and the glory of the world. Certain I am that Kána-aná never wearied me with his attentions, though they were incessant. Day and night he was by me. When he was silent, I knew he was conceiving some surprise in the shape of a new fruit, or a new view to beguile me. I was, indeed, beguiled; I was growing to like the little heathen altogether too well. What should I do when I was at last compelled to return out of my seclusion, and find no soul so faithful and loving in all the earth beside? Day by day this thought grew upon me, and with it I realized the necessity of a speedy departure.

There were those in the world I could still remember with that exquisitely painful pleasure that is the secret of true love. Those still voices seemed incessantly calling me, and something in my heart answered them of its own accord. How strangely idle the days had grown! We used to lie by the hour—Kána-aná and I—watching a strip of sand on which a wild poppy was nodding in the wind. This poppy seemed to me typical of their life in the quiet valley. Living only to occupy so much space in the universe, it buds, blossoms, goes to seed, dies, and is forgotten.

These natives do not even distinguish the memory of their great dead, if they ever had any. It was the legend of some mythical god that Kána-aná told me, and of which I could not understand a twentieth part; a god whose triumphs were achieved in an age beyond the comprehension of the very people who are delivering its story, by word of mouth, from generation to generation. Watching the sea was a great source of amusement with us. I discovered in our long watches that there is a very complicated and magnificent rhythm in its solemn song. This wave that breaks upon the shore is the heaviest of a series that preceded it; and these are greater and less, alternately, every fifteen or twenty minutes. Over this dual impulse the tides prevail, while through the year there is a variation in their rise and fall. What an intricate and wonderful mechanism regulates and repairs all this!

There was an entertainment in watching a particular cliff, in a peculiar light, at a certain hour, and finding soon enough that change visited even that hidden quarter of the globe. The exquisite perfection of this moment, for instance, is not again repeated on to-morrow, or the day after, but in its stead appears some new tint or picture, which, perhaps, does not satisfy like this. That was the most distressing disappointment that came upon us there. I used to spend half an hour in idly observing the splendid curtains of our bed swing in the light air from the sea; and I have speculated for days upon the probable destiny awaiting one of those superb spiders, with a tremendous stomach and a striped waistcoat, looking a century old, as he clung tenaciously to the fringes of our canopy.

We had fitful spells of conversation upon some trivial theme, after long intervals of intense silence. We began to develop symptoms of imbecility. There was laughter at the least occurrence, though quite barren of humor; also, eating and drinking to pass the time; bathing to make one's self cool, after the heat and drowsiness of the day. So life flowed out in an unruffled current, and so the prodigal lived riotously and wasted his substance.

There came a day when we promised ourselves an actual occurrence in our Crusoe life. Some one had seen a floating object far out at sea. It might be a boat adrift; and, in truth, it looked very like a boat. Two or three canoes darted off through the surf to the rescue, while we gathered on the rocks, watching and ruminating. It was long before the rescuers returned, and then they came empty-handed. It was only a log after all, drifted, probably, from America. We talked it all over, there by the shore, and went home to renew the subject; it lasted us a week or more, and we kept harping upon it till that log—drifting slowly, O how slowly! from the far mainland to our island—seemed almost to overpower me with a sense of the unutterable loneliness of its voyage. I used to lie and think about it, and get very solemn, indeed; then Kána-aná would think of some fresh appetizer or other, and try to make me merry with good feeding. Again and again he would come with a delicious banana to the bed where I was lying, and insist upon my gorging myself, when I had but barely recovered from a late orgie of fruit, flesh, or fowl. He would mesmerize me into a most refreshing sleep with a prolonged and pleasing manipulation. It was a reminiscence of the baths of Stamboul not to be withstood. From this sleep I would presently be wakened by Kána-aná's performance upon a rude sort of harp, that gave out a weird and eccentric music. The mouth being applied to the instrument, words were pronounced in a guttural voice, while the fingers twanged the strings in measure. It was a flow of monotones, shaped into legends and lyrics. I liked it amazingly; all the better, perhaps, that it was as good as Greek to me, for I understood it as little as I understood the strange and persuasive silence of that beloved place, which seemed slowly but surely weaving a spell of enchantment about me. I resolved to desert peremptorily, and managed to hire a canoe and a couple of natives, to cross the channel with me. There were other reasons for this prompt action.

Hour by hour I was beginning to realize one of the inevitable results of Time. My boots were giving out; their best sides were the uppers, and their soles had about left them. As I walked, I could no longer disguise this pitiful fact. It was getting hard on me, especially in the gravel. Yet, regularly each morning, my pieces of boot were carefully oiled; then rubbed, or petted, or coaxed into some sort of a polish, which was a labor of love. O Kána-aná! how could you wring my soul with those touching offices of friendship!—-those kindnesses unfailing, unsurpassed!

Having resolved to sail early in the morning, before the drowsy citizens of the valley had fairly shaken the dew out of their forelocks, all that day—my last with Kána-aná—I breathed about me silent benedictions and farewells. I could not begin to do enough for Kána-aná, who was, more than ever, devoted to me. He almost seemed to suspect our sudden separation, for he clung to me with a sort of subdued desperation. That was the day he took from his head his hat—a very neat one, plaited by his mother—insisting that I should wear it (mine was quite in tatters), while he went bareheaded in the sun. That hat hangs in my room now, the only tangible relic of my prodigal days. My plan was to steal off at dawn, while he slept; to awaken my native crew, and escape to sea before my absence was detected. I dared not trust a parting with him, before the eyes of the valley.

Well, I managed to wake and rouse my sailor boys. To tell the truth, I didn't sleep a wink that night. We launched the canoe, entered, put off, and had safely mounted the second big roller just as it broke under us with terrific power, when I heard a shrill cry above the roar of the waters. I knew the voice and its import. There was Kána-aná rushing madly toward us; he had discovered all, and couldn't even wait for that white garment, but ran after us like one gone daft, and plunged into the cold sea, calling my name, over and over, as he fought the breakers. I urged the natives forward. I knew if he overtook us, I should never be able to escape again. We fairly flew over the water. I saw him rise and fall with the swell, looking like a seal; for it was his second nature, this surf-swimming. I believe in my heart I wished the paddles would break or the canoe split on the reef, though all the time I was urging the rascals forward; and they, like stupids, took me at my word. They couldn't break a paddle, or get on the reef, or have any sort of an accident. Presently we rounded the headland,—the same hazy point I used to watch from the grass house, through the little window, of a sunshiny morning. There we lost sight of the valley and the grass house, and everything that was associated with the past,—but that was nothing. We lost sight of the little sea-god, Kána-aná, shaking the spray from his forehead like a porpoise; and this was all in all. I didn't care for anything else after that, or anybody else, either. I went straight home and got civilized again, or partly so, at least. I've never seen the Doctor since, and never want to. He had no business to take me there, or leave me there. I couldn't make up my mind to stay; yet I'm always dying to go back again.

So I grew tired over my husks. I arose and went unto my father. I wanted to finish up the Prodigal business. I ran and fell upon his neck and kissed him, and said unto him, "Father, if I have sinned against Heaven and in thy sight, I'm afraid I don't care much. Don't kill anything. I don't want any calf. Take back the ring, I don't deserve it; for I'd give more this minute to see that dear, little, velvet-skinned, coffee-colored Kána-aná, than anything else in the wide world,—because he hates business, and so do I. He's a regular brick, father, moulded of the purest clay, and baked in God's sunshine. He's about half sunshine himself; and, above all others, and more than any one else ever can, he loved your Prodigal."

For a week, Charlie agonized over the submission and what it would mean for his career—and his life.

When Harte finally returned to the City for a day, he summoned Charlie to the Overland offices. Charlie slunk into the office, head bowed, expecting censure, recrimination, ruin—even arrest and prison.

Harte sat behind his desk, Chumming with a Savage on the blotter in front of him.

“Hello, Stoddard. You look well.”

Salutations before the execution, Charlie thought, and swallowed hard. Harte lifted the manuscript. And then to Charlie’s wonderment, he smiled.

“Now you have struck it! It shall run in the next issue. Keep on in this vein and presently you will have enough to fill a volume and you can call it South Sea Bubbles.”

Charlie was almost dumb with amazement.

He stammered his thanks and stepped out of Harte’s office in a fog. Had Harte not grasped the implications of his story? Or could it be that there had never been cause for anxiety?

He suddenly realized Ina was sitting at her own desk, watching him. In his agitation he’d walked by her without even seeing her. She dropped her gaze to the desk and he knew instantly that she had read it—and on her, no implications had been lost.

“And what says the Sapphic Divinity?” he asked, tremulously.

“I do think you’ve struck it.” She lifted her eyes to his for a moment. “It reads as truth.”

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning: