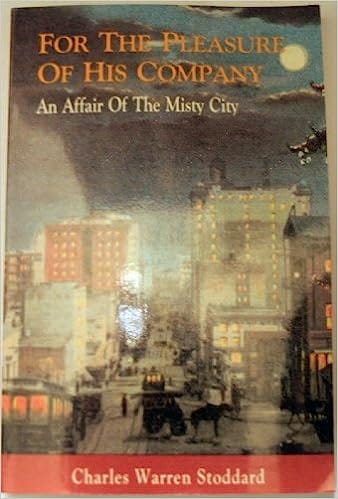

Pride Month - Charlie Stoddard: "The idealized duality of sex"

San Francisco poet and journalist Charles Warren Stoddard (1843-1909) wrote the first acknowledged American novel about openly gay characters (The Pleasure of His Company, 1903), and long before that, lived out in a time that had not yet heard the word homosexual. To me, he’s an obvious founding father of San Francisco’s vibrant, vital and beloved gay community.

His friends were the creme de la creme of Bohemian San Francisco: Mark Twain, Ina Coolbrith, Bret Harte, Ambrose Bierce, Ada Clare, Adah Isaacs Menken. He wrote for all the best California journals and newspapers: The Golden Era, The Overland Monthly, the San Francisco Chronicle (owned and operated by his old schoolmate, the volatile Charles de Young).

Though Charlie at first kept his longings to himself, he soon grew bolder in private and public life. His friends and colleagues all knew he loved men. They were not simply tolerant but protective of him.

He began his writing career as a teenage poet, and soon became one of California’s best and best-known. But he really found his niche as a travel writer—no ordinary travel writer, but one who daringly chronicled his affairs with young native men in Hawaii and the South Seas. Some San Francisco readers probably didn’t quite grasp the extent of these relationships—others knew full well. But amazingly for the time, no one ever complained.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Chapter 76

Oakland, California - Fall, 1863

Charles Warren Stoddard, age 20

Charles Warren Stoddard, 1843 –1909

Charlie leaned against the rail on the top deck of the ferry, enjoying the ruffle of the bay breeze in his hair. Railroad and ferry connection between San Francisco and Oakland had been established on the first of September.

The Bay was no South Seas—but even this short journey was some freedom from the Academy.

Reverend Starr King had urged Charlie to go back to finish his schooling at Oakland’s Drayton Academy, and Charlie could deny the minister nothing. But he hated school beyond what words could express.

He conned his textbook by the hour and honestly endeavored to make its contents all his own forever, yet in the end he seemed to have accomplished little—and that little left him when the class was called. He was simply unable to gather knowledge in the conventional way.

And there were ever so many distractions.

Every weekend he took the ferry across the Bay to stay at his parents’ house on Russian Hill, and he forgot his sorrows by sinking into the familiar night life of the city, reveling in the beautiful women in bewildering attire, the exotic foreign quarters, the sights that young and innocent eyes ought never to be laid on.

And in San Francisco he was able to put pen to paper and release the feelings that threatened to overwhelm him at the Academy:

“Once there was a fellow at school who caught my eye and held it. He seemed to me little less than Godlike. I had never before seen such eyes, such curly hair, such a haughty mean in the youth of eighteen or nineteen. He had scorn of everybody and everything – save only himself. Me, he ignored utterly even while I worshiped silently in his presence and secretly wished that I might die for his sake; for his briefest pleasure I felt that I would joyfully return to dust. Such is the heart of youth when it has been touched by the spirit of romance!

At the close of his first term at school he, one day, wanted a match. We were all in the campus in holiday attire; all in high spirits and most of the fellows were at his feet. I worshipped silently and apart as was my wont. Oh, blessed day! It chanced that there wasn’t a match in the crowd.

But I was not in the crowd; I was never in the crowd.

I had a match.

Having become desperate in his fruitless search for a match he, at the last moment, discovered me. I thought I heard a voice from heaven crying for a match. Kismet! My hour had come!

He asked me in the doubtfullest way if I had a match and I produced one. It was the proudest moment of my life. The dews of joy were damp upon my brow; my heart turned over with the light. I wished I were a match that he might strike my head against something and consume me at the tip of his cigarette.

He condescended to take my trembling match and turned away without uttering one syllable of thanks. Had I been a paper matchbox he could not have treated me with more indifference. My admiration of his haughtiness was boundless. I felt that I had not lived in vain. The one word, the one moment had atoned for the draining of a cup of bitterness that was forever brimming over.

In his story, Charlie’s idol became his willing slave. But in reality, alas, Charlie was ever apart from the young gods of the school. And he trembled at the very idea of submitting such a story to any of the journals which were now regularly publishing his poetry.

But his thoughts turned more and more often to variations on the theme.

In San Francisco that fall, the biggest sensation available for purchase was the play Mazeppa, presented by impresario Tom McGuire, featuring New York actress Ada Menken in bold and scandalous casting as the young male Arabian hero.

The performance was as risqué as the waves of talk promised. Not only because “La Menken” portrayed the male lead. The play climaxed with a sensational scene of Mazeppa being stripped to flesh-colored tights and strapped to the saddle of a live horse, which then thundered off stage with the writhing and quite naked-appearing Menken on its back.

It played to a full house every night, so popular that the Golden Era joked, “People who have not been, and who do not intend to go, will be exhibited at the close of another week in glass cages.”

It was all the talk at the Era that weekend. Charlie floated in to the news office, having seen the play the night before, to find Frank Harte and Charles Webb lounging behind their desks, dissecting it.

Apparently Harte had not been impressed.

“Twain has it dead to rights.” He took up the Territorial Enterprise and read aloud from Mark Twain’s review of the Virginia City production. “Here every tongue sings the praises of her matchless grace, her supple gestures, her charming attitudes… She bends herself back like a bow; she pitches headforemost at the atmosphere like a battering ram, she works her arms, and her legs, and her whole body like a dancing-jack… in a word, she carries on like a lunatic from the beginning of the act to the end of it. At other times she whallops herself down on the stage and rolls over like the sportive pack-mule after his burden is removed. If this be grace then ‘the Menken’ is eminently graceful.”

He lowered the paper, and noticed Charlie had entered the office. “We were just discussing Menken. What say you, Stoddard?”

A rapturous look came over Charlie’s face. “She is a living and breathing poem that sets the heart to music… and throbs rhythmically to a passion that is as splendid as it is pure—”

The other two men burst out laughing, giving each other knowing looks. “Th-the Menken c-claims another scalp,” Webb chortled in his characteristic stutter.

Charlie laughed with them, and said nothing.

They mistook him entirely, of course. Charlie did not want Menken. He wanted to be Menken.

As he’d sat in the theater watching the play, he had felt the heat rising from the mesmerized audience, until he’d felt quite faint. He wanted to be the one in clinging tights. He wanted to feel the horse’s power and hot, sweating muscles between his legs. He wanted to be the object of the audience’s lust.

And Menken’s performance! She had thrown off all restriction of feminine movement. She had broken all rules of expected behavior and achieved a half-feminine masculinity that was entirely enthralling. One reviewer had expressed it perfectly as an “idealized duality of sex.”

The exhilaration of it was overwhelming… and a profound relief to Charlie.

He was not alone in his strangeness.

Menken stayed in the City for a thrilling four months, performing Mazeppa and various comedies. Breathless reports had her gambling the night away in casinos dressed in male clothing and smoking cigars. She had been seen escorting seventeen-year-old darling of the theatrical set, Lotta Crabtree, to various restaurants, inciting wild speculation.

Charlie followed all the gossip, in delight and some outrage, as he knew The Menken was no mere actress! She contributed poetry to the Era.

But mostly, she set his fantasies on fire. In his private notebook, he dreamed of inhabiting a woman’s body: Menken’s, Ada Clare’s, Ina’s…. so that his physique could be made whole.

As ever, he kept his thoughts on the subject to himself.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Incredible writing, Alexandra!! You've woven the words of these historical characters in with yours... gorgeous artwork!!