"It is time for stronger remedies to be applied, in the form of hot lead and cold steel duly administered by 100,000 Black doctors." - Abolitionist Wendell Phillips

“Frederick Douglass told Abe Lincoln, 'Give the black man guns and let him fight.' And Abe Lincoln say, 'If I give him a gun, when it come to battle he might run.' And Frederick Douglass say, 'Try him, and you'll win the war.' And Abe said, 'All right, I'll try him.'"

- Cornelius Garner, Union soldier

So many people in the US right now are in despair. We are wondering how after such a long, fraught path toward freedom and equality we could possibly have slid so terrifyingly far backwards, so quickly. But I keep reminding myself that 200 years ago, 100 years ago, 60 years ago, it was worse. So far, far worse that it’s incredible that we ever moved forward out of that moral, social, political abyss.

I think one key to the fight ahead is looking back to see how we ever made social and moral progress in the first place.

In my story structure Substack I’m breaking down the movie Selma because besides being such a great teaching movie for authors and screenwriters, it’s also a textbook of social action. The screenplay and movie lay out precise steps for civil action. And the movie shows Martin Luther King Jr. and his team of activists putting intense, carefully designed pressure on President Lyndon Johnson to do the right thing.

Well, studying Abraham Lincoln’s progress toward supporting Emancipation is also a textbook in social action.

If you go by the history most of us are taught in school, Lincoln liberated the enslaved as soon as he had the power to do so, and we lived happily ever after, amen.

But the truth was a lot — slower.

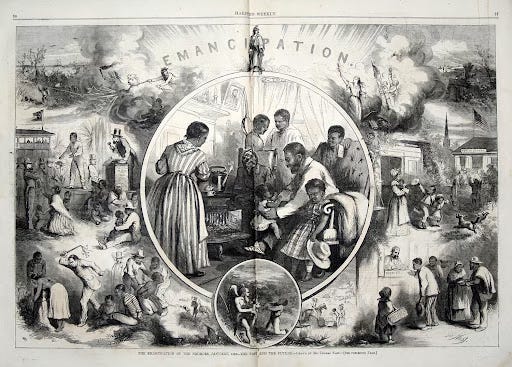

Emancipation was a painfully gradual process and was fought for, literally, and paid for, literally, in blood. A huge part of that process was changing Lincoln’s mind on the subject.

I’m not going to pretend I know what Lincoln was thinking, and what was his process of coming around to advocating and legislating total Emancipation. But brilliant historians have parsed his letters, speeches, anecdotes from other people, to come to fascinating conclusions. And it is really illuminating and useful for our times to understand that it WAS a process.

At first the morality of freedom and equality didn’t seem to factor into his decisions as President at all. He only used Emancipation as a threat to seceded Southern states, dangling a carrot in front of Confederate leaders that if they returned to the Union, they’d get to keep “their” enslaved.

Black leaders, especially Frederick Douglass, Black newspaper editors, Black and white abolitionists, all worked tirelessly and relentlessly to put pressure on Lincoln in various ways before he moved from a legal stance to a moral one.

Now, I’m not for one second saying that there’s a hope in hell of persuading the man occupying the Oval Office of anything resembling morality. But I’m hearing (reading) a lot of activists looking at Democratic leaders and lamenting “Where’s our Lincoln?”

And it made me want to suggest that even Lincoln had to be galvanized by activists to become the leader we needed him to be.

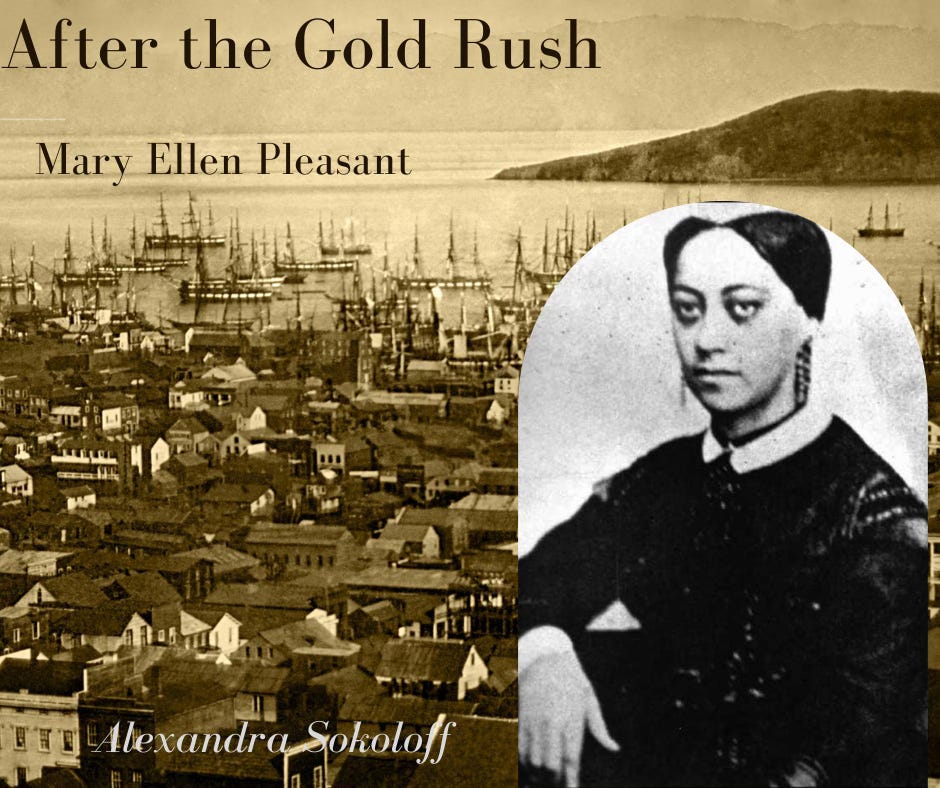

As part of the After the Gold Rush project, I’ve dramatized part of that battle below, using real people and real dialogue from their news articles, letters and autobiographies.

After the Gold Rush - Chapter 53

July 17, 1862 — San Francisco, California

Mary Ellen Pleasant, the Executive Committee

It had been the gloomiest Fourth of July imaginable, after a series of Union defeats.

I was invited again when the Executive Committee met to plan for a September celebration of the emancipation of slaves in the District of Columbia back in April. At the meeting we also discussed the news, which, as they say, was mixed.

Shiloh had been a Union success— strategically. But it was truly a shock to the country when those terrible casualty lists came out in the newspapers.

In the Seven Days Battles, McClellan’s Union Army of the Potomac invaded Virginia, but from June 25 to July 1, General Lee drove them away from Richmond and into retreat down the Virginia Peninsula. The Peninsula Campaign ended in defeat, crushing Northern morale while Southern spirits soared.

California chose to celebrate the Pacific Railroad Bill instead, with a grand torchlight demonstration of firemen in its honor.

Lincoln continued to resist enlisting Black soldiers. He told a delegation: “To arm the negro would turn fifty thousand bayonets against us that were for us.”

But the horrific loss of Union men, eighteen thousand more souls in the Peninsula campaign, opened a door to press the issue. And it was heartening that Congress took the bit in its teeth. The Republicans, now in a majority, were far quicker than the President to act.

In June, Congress abolished slavery forever in the Western Territories.

On July 17, Congress passed The Second Confiscation Bill, emancipating all slaves in states engaged in rebellion, not just those engaged in the field or military services, in order to use all the physical force at the Union’s disposal.

I suppose they had to frame it as “confiscation” to get it passed, but that didn’t mean I liked it.

Everyone assumed that Lincoln would veto the bill, but he surprised us all and signed, with restrictions. There was no practical means of enforcement, but it worked—mostly because our people kept escaping in droves and showing up at Union encampments, ragged, starving—and ready to fight or work.

And the new Militia Act enrolled Negroes “in any military or naval service to which they may be found competent.” Black militias were already being raised in Louisiana, Kansas, and South Carolina.

We had eyes and ears in Washington, too. TMD Ward had written us, “The President is making secret plans for an Emancipation Proclamation, while still trying to retain the loyalty of the border states.”

At the meeting, Pacific Appeal editor Peter Anderson was downright optimistic. “It shows his mind is changing.”

San Francisco's Black newspapers, Civil War era

San Francisco’s “Executive Committee” was a group of educated Black elite: ministers, teachers, business owners, from across California who came together and consolidated power through the California Colored Convention in 1855. They implemented programs and policies that would benefit the Black population throughout California.

The Reverend J.J. Moore nodded. “And I believe the President is trying. He proposed compensation for gradual emancipation in the border states in March, and again in July.”

Anderson’s co-editor Philip Bell was clearly less convinced. As usual, I was hanging back, listening rather than talking. But Bell brought up the very point I would have made: “And the border states refused, and Lincoln has not pressed the issue. And what if the border states secede to the South?”

Anderson immediately blustered, “None of us has a crystal ball—”

Bell didn’t even let him finish. “You know as well as I that the Union would be overwhelmed. We must win the war to win our freedom.”

J.J. stepped in to smooth things over. “It is strongly suspected that the President is waiting for a decisive Union victory to announce Emancipation.”

In fact, Lincoln moved sooner than we thought. He assembled his cabinet on July 22 to read them a draft of a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation that was far more radical than anything that he’d discussed before. There would be no cumbersome enforcement or gradual legislation. The Proclamation would set January 1, 1863, as the date on which all enslaved persons in states still in rebellion would be “thenceforth and forever free.”

It wasn’t about freedom. It was practical. It meant that massive workforce of Southern slaves, three and a half million of our people, would be instantly transferred from the Confederacy to the Union. It also only applied to the Confederate states, not the border states of Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky and Missouri. Lincoln intended to promise them they could keep their “property” if they stayed loyal to the Union.

To be fair, as far as I was willing to be, Lincoln was wrestling with a Cabinet and a country in which many white people, if not most, believed that our two races could not exist and thrive in social proximity. That equality meant the degradation and demoralization of the white race.

Lincoln’s own Attorney General Edward Bates said it straight out:

“I cannot imagine former slaves, fresh from the plantations of the South, where they have been long degraded by the total abolition of the family relation, shrouded in artificial darkness, and studiously kept in ignorance — living on an equal footing with whites.”

Well, personally, I couldn’t imagine former slave masters, fresh from the plantations of the South, where they have been long degraded by their own total lack of human feelings or Christian decency, living shrouded in the darkness of their own sin, deliberately basking in their own ignorance — ever living on an equal footing with Blacks.

The Committee could knock itself out trying to prove to inhuman people that we were human.

I was with Douglass on this one:

“Am I to argue that it is wrong to make men brutes, to rob them of their liberty, to work them without wages, to keep them ignorant of their relations to their fellow men, to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash, to load their limbs with irons, to hunt them with dogs, to sell them at auction, to sunder their families, to knock out their teeth, to burn their flesh, to starve them into obedience and submission to their masters?

Must I argue that a system thus marked with blood, and stained with pollution, is wrong? No! I will not. I have better employment for my time and strength than such arguments would imply.”

And so did I. I had my own work to do.

Chapter 55

September 1862 —San Francisco

Mary Ellen Pleasant, the Executive Committee

On September 1, we held our grand festival in Hayes’ Park to celebrate the emancipation of slaves in the District of Columbia in April, on the anniversary of the emancipation of slaves in the British West Indies in 1834. A national salute was fired at noon.

The Reverend Thomas Starr King spoke before a large audience, mostly Black, at Pacific Gardens. It was strategic, of course, inviting him to speak. Anywhere the Reverend orated, people showed up, and newspapers carried the news. But the man meant what he said:

“The Almighty had a great mission for this nation. Here the church was to proclaim the equality of the races.”

I have to admit, I got choked up, watching him: this little man who radiated so much light. And so maybe I had a sense of what was coming. But at the time, I just thought, If only more churches felt the same. If only our President did.

We were all still waiting for the Emancipation Proclamation. If Lincoln was holding off for a decisive Union victory to announce it, there were none to be seen that summer. Through the summer, the Army continued to be battered. Union troops were horribly defeated at the second Battle of Bull Run on August 29-30, and retreated to Washington.

And then came Antietam.

Having routed McClellan’s army, Lee decided to invade the North, to take the war into Northern territory and convince Britain to support the Confederacy.

It was a big mistake.

He crossed the Potomac September 4th.

Antietam, September 17, was the bloodiest day of the war so far. Six hundred dead. The Union suffered the most casualties, and because McClellan maddeningly didn’t pursue Lee’s army, Lee was able to withdraw back to Virginia and regroup. All in all, the battle was militarily inconclusive. But it was pivotal to the Union cause. We’d halted Lee’s invasion of Maryland. More importantly, before Antietam, England was on the verge of entering the war on the Confederate side. After Antietam, Britain and France dropped their offer to mediate a peace on the basis of Confederate independence. That was huge.

And it seemed the victory was what Lincoln had been waiting for. He fired McClellan, for not pursuing Lee’s army.

And five days after the battle, on September 22, he issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, warning the Confederacy that slaves in the states in rebellion would be freed on January 1st. unless the rebelling states returned to the Union by the new year.

It was what our community had been waiting for, too.

“We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree,” Douglass wrote in his Monthly.

But of course, doubts crept in immediately. At the next Executive Committee meeting, Philip Bell once again said exactly what I was thinking. “Lincoln’s still using the Proclamation as a carrot and stick. He may yet retract.”

Peter Anderson retorted, “Abraham Lincoln will take no step backward. Abraham Lincoln may be slow, but Abraham Lincoln is not the man to reconsider, retract and contradict words and purposes solemnly proclaimed over his official signature. If he has taught us to confide in nothing else, he has taught us to confide in his word.”

I knew he was just parroting Douglass, but if you’re going to quote someone, who better?

To my mind, Lincoln had left the Confederacy a big out. They could come back to the Union by January 1st, and not be crushed by the Union Army. And if they did, they’d get to keep their enslaved.

The South wasn’t going to do it, of course. But that didn’t make me like it any more that our freedom was on offer.

The President also formally authorized the recruitment of Black men into the Union Armies and Navy. And to win public support, he wrote a very public letter to James Conkling, Republican Congressman from Illinois, who was very publicly opposing Emancipation. Conkling’s position was that white Northerners wouldn’t accept Emancipation. He said white northern soldiers would throw down their arms and say, "I ain't fighting to free the slaves. I'm fighting to preserve the Union." Surely Lincoln had that fear himself. Because that’s what they did say, most of ‘em.

What Lincoln said to that was,

"You dislike the Emancipation Proclamation, and perhaps would have it retracted. You say it is unconstitutional. I think differently. I think the Constitution invests its commander-in-chief with the law of war, in time of war. The most that can be said, if so much, is that the slaves are property. Is there, has there ever been any question that by law of war property, both of enemies and friends, may be taken when needed?"

Yes, my blood boiled at that. But I saw what he was doing. The man was a lawyer. He was asserting what Constitutional authority he believed he had.

"You say you will not fight to free Negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you. But no matter, fight you then, exclusively to save the Union. I issued the Proclamation on purpose to aid you in saving the Union…I thought that in your struggle for the Union, to whatever extent the Negroes should cease helping the enemy, to that extent it weakened the enemy in his resistance to you. Do you think differently? I thought that whatever Negroes can be got to do as soldiers leaves just so much less for white soldiers to do in saving the Union."

Say whatever else you will, that struck me as an argument that would appeal to white soldiers.

We read the Conkling letter over and over. Endlessly analyzing passages like this:

"But Negroes, like other people, act upon motives. Why should they do anything for us if we will do nothing for them? If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive, even the promise of freedom. And the promise being made must be kept."

We parsed this letter. We argued from one moment to the next about Lincoln’s intent.

“He’s changing his mind.” “Is he changing his mind?”

How I hated being reliant on this man. Hell, I hated being reliant on any man. But for the first time, I allowed myself to hope.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Alexandra Sokoloff:

I’m a bestselling feminist crime and thriller author —but I also have a commitment and a platform to write about history that isn’t often talked about in the generalizations and most often outright whitewashing and male-washing of history textbooks.

Under this regime, working to counteract the whitewashing and suppression of history is going to be more important than ever.

Why subscribe?

After the Gold Rush is a reader-supported publication. To receive a monthly roundup of new posts and support this work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Likes, Shares and Comments are extremely helpful and much appreciated!