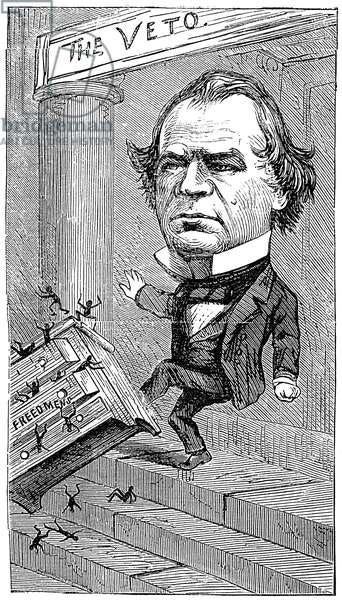

“Andrew Johnson, wont to look up to the planters as a superior race, cannot resist their condescensions & flatteries… and was an easy victim for their caresses.”

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

Chapter 116

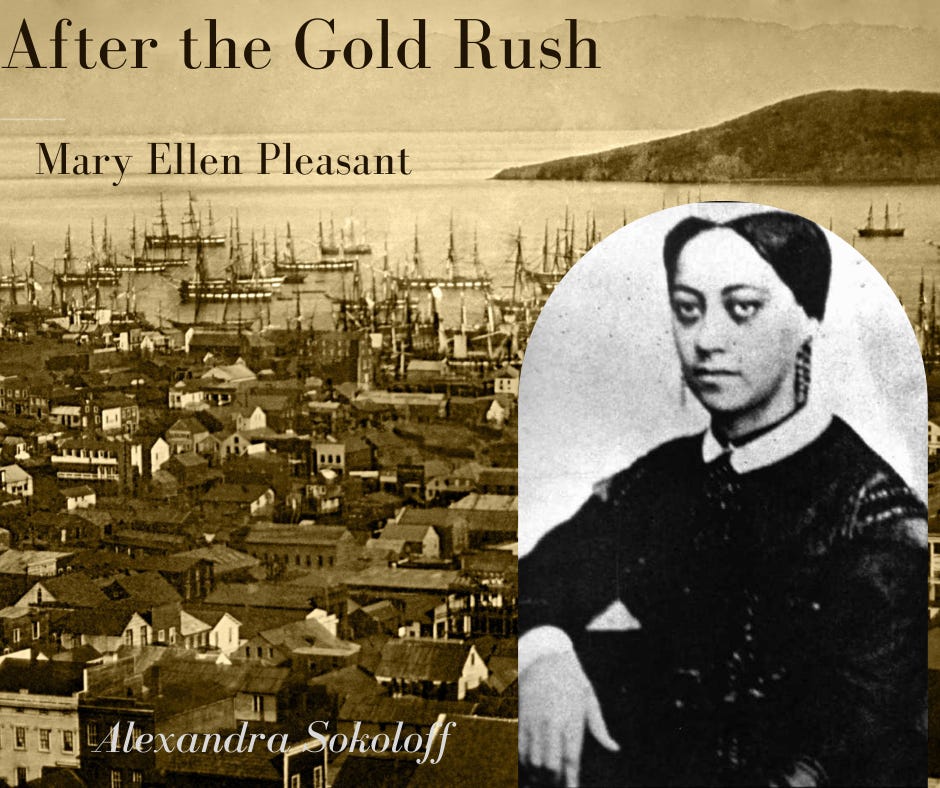

San Francisco, California, April-June 1865

Mary Ellen Pleasant

During the City’s official mourning period for the slain President, Alcatraz’ batteries shot a cannon out over the bay every half-hour, as a symbol of the City’s and nation’s grief for Father Abraham.

I flinched every time I heard it. Surely it was only making things worse.

While the rest of California was rocked by the horror of Lincoln’s assassination, my people were struck in the same moment with an even greater horror.

Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, a former slaveholder, was now President.

Johnson had served as Lincoln's running mate in 1864 on the so-called National Union ticket, which was designed to attract Republicans and War Democrats. He was an expediency, an appeasement made without fully grasping the consequence of what it would mean should the unthinkable happen.

The unthinkable had happened. And now we could all see the unthinkable had always been painfully inevitable. The logical culmination of the nation’s racial hate.

For all that I’d distrusted Lincoln, I would have given my very soul to have him back. The taste of fear was bitter in my mouth.

From Frederick Douglass himself, we knew the character of our new President. Douglass had been a guest at Lincoln’s second inaugural. Johnson had been drunk and sloppy—a frequent state of his, apparently—and he let decorum slip. Upon being introduced to Douglass he gave him a look of sheer hatred and refused to shake his hand.

From Douglass we knew: whatever else Johnson was, he was no friend of our people. He would never for a single second accept our race as human.

I confess, I had been so occupied with Thomas, with finance and otherwise, that I had not been attending many Executive Committee or newspaper meetings. Now I was driven to every gathering. I needed to hear news that was not from a white source.

I learned that in May, Major General Oliver Howard was given charge of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands. Lincoln had conceived the Freedman’s Bureau; the bill to authorize it was passed in March.

It was meant to exist for just one year, and Howard had just one hundred agents to work with. The budget was about what it cost to fight the war for one week. With such sorry resources, the Freedmen’s Bureau was pretty much solely responsible for all the practical work of Reconstruction: advocating for the formerly enslaved, ensuring equal protection in the courts, helping newly free people make a living, offering food rations, negotiating labor contracts, establishing schools. All while constantly fighting the efforts, tricks and crimes perpetrated by ex-Confederates—who scarcely thought of themselves as “ex” at all—to sabotage their efforts.

Did anyone in the country believe one hundred men were enough to keep four million freed people safe from fifteen thousand former slave owners? Did anyone think the slavers were just going to wake up one morning and not want their slaves back? After years of rape and torture and domination, they were just going to suddenly see the shining light?

I’d lived under the slave powers. I’d looked straight into the blackest of hearts. With years, decades, of re-education, maybe a few would grow a conscience.

Look at what happened in Texas, just for one thing. The Emancipation Proclamation officially freed the enslaved there back in January 1863. But it wasn’t until Union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865, that anyone actually told those 250,000 people they were free. Even when General Granger announced it in Galveston, you bet that some slave powers didn’t let on until after the harvest.

You ask me, it would take the whole Union army sitting on top of the South for twenty years—or a hundred—to change anything.

And that wasn’t going to happen. For white people, the fighting was done. They just wanted to go back to their lives.

But what Howard did have to work with was 850,000 acres of Southern land that had been confiscated, abandoned, or lost to debt and taxes.

At the end of July, 1865, Howard started a process to make Sherman’s Field Order Number 15 a reality. He gave his agents the order to start renting out forty acre plots. At the end of three years, the freedmen would be able to buy the land.

“Forty acres and a mule” could have been the economic basis for Reconstruction, and a new lease on life for our people.

And I guess the Republicans wanted to believe that Johnson would get Reconstruction done. Before and during the war, he’d talked a good game. He was violently opposed to the dissolution of the Union. He was the only Southerner to stay in the Senate when war broke out. As vice president, he denounced Confederates as “infamous of character and diabolical of motive.” While Lincoln counseled forgiveness and reconciliation, Johnson was proclaiming, “I would arrest them; I would try them; I would convict them, and I would hang them.” And “Treason must be made odious.”

Well, they believed him. No less a Radical than Senator Benjamin Wade threw himself behind the new president, exclaiming, “Mr. Johnson, I thank God that you are here. Lincoln had too much of the milk of human kindness to deal with these damned rebels. Now they will be dealt with according to their deserts.”

But within weeks, Johnson showed his true colors.

If Congress had been in session, it might never have happened. But Congress was in recess till December, so Johnson had no opposition. He could have called Congress back, but why would he do that? He got himself right in there to reconstruct the South all by himself. He didn’t even bother to call it Reconstruction. To him it was “Restoration.”

Restoration to a slave system, by a new name.

I’d seen plenty of Johnsons in my time in my years in Georgia and Louisiana.

He’d grown up a poor boy and blamed the war on the planter class, who had always looked down on him and whom he resented mightily. He used his new power over Reconstruction to get revenge. He issued general pardons to Southerners who took the oath to the Union. But any former slaveowner who had an estate worth twenty thousand or more wasn’t covered by the blanket pardon. They had to come to Washington and personally appeal on their knees to the President for a pardon and restoration of their lands. If the planter groveled sufficiently, Johnson ordered his lands restored.

So all that land that had been confiscated by the Union Army and distributed to the freedmen by the army or the Freedmen’s Bureau got taken away and given right back to its prewar owners. To our prewar owners.

Southern states had to take the oath of loyalty to the Union, comply with the abolition of slavery, and pay off war debt. Other than that, Southern state governments were given free rein to rebuild themselves.

And can anyone guess how that went?

It was the end of forty acres and a mule.

Johnson also allowed the Southern states to set up their own governments again and allowed them a free hand to keep the former slaves under control. State conventions charged with writing new constitutions weren’t even required to allow Black men to participate.

By the end of the summer, the same damn slaveowners who started the war were back in power and there was not a damn thing Congress could do about it.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning: