A key reason I decided to write After the Gold Rush as novelized history, rather than a historical novel, is that once I’d submerged myself in the research I quickly realized that the real words and real experiences of the real people I was writing about were much more interesting and important than any fictional depiction could ever be.

And in a time when would-be authoritarians and religious zealots are trying to whitewash and censor the real history of the United States, I feel it’s more important than ever to tell these stories as they happened.

Charlie Stoddard was one of the figures that convinced me to go the real-life route.

Charles Warren Stoddard, 1843 –1909

Charlie wrote the first acknowledged American novel about openly gay characters (The Pleasure of His Company, 1903), and long before that, lived out in a time that had not yet heard the word homosexual. To me, he’s an obvious founding father of San Francisco’s vibrant, vital and beloved gay community.

His friends were the creme de la creme of Bohemian San Francisco: Mark Twain, Ina Coolbrith, Bret Harte, Ambrose Bierce, Ada Clare, Adah Isaacs Menken. He wrote for all the best California journals and newspapers: The Golden Era, The Overland Monthly, the San Francisco Chronicle (owned and operated by his old schoolmate, the volatile Charles de Young).

Though Charlie at first kept his longings to himself, he soon grew bolder in private and public life. His friends and colleagues all knew he loved men. They were not simply tolerant but protective of him.

He began his writing career as a teenage poet, and soon became one of California’s best and best-known. But he really found his niche as a travel writer—no ordinary travel writer, but one who daringly chronicled his affairs with young native men in Hawaii and the South Seas. Some San Francisco readers probably didn’t quite grasp the extent of these relationships—others knew full well. But amazingly for the time, no one ever complained.

One of the great things about being a writer is these incredible people take up permanent residence in your head. Discovering Charlie’s adventures on the page and in real life is a constant delight to me.

It’s my pleasure to introduce you to Charlie Stoddard.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Chapter 60

San Francisco, California, September-October 1862

Charles Warren Stoddard (age 19)

The Chileon Beach bookshop, directly across from the Lick House on Montgomery Street was no competition for the amazing Bancroft & Co. around the corner on Merchant, with its three stories of books on all possible subjects. Chileon Beach was disappointingly stocked, almost entirely Bibles. Female customers agreed the shop’s only redeeming quality was its young clerk, who looked about fourteen, and had a face like an angel from a Raphael painting.

Charlie Stoddard delighted in the paucity of customers. It meant when his employer was out of the shop, he could write to his heart’s content.

Behind the counter he had a sheet of paper and a fountain pen concealed on a shelf. The page was covered in scrawls and crossings-out, and Charlie could occupy himself for hours, staring dreamily into space, then scribbling down inspired lines.

Charlie was a poet.

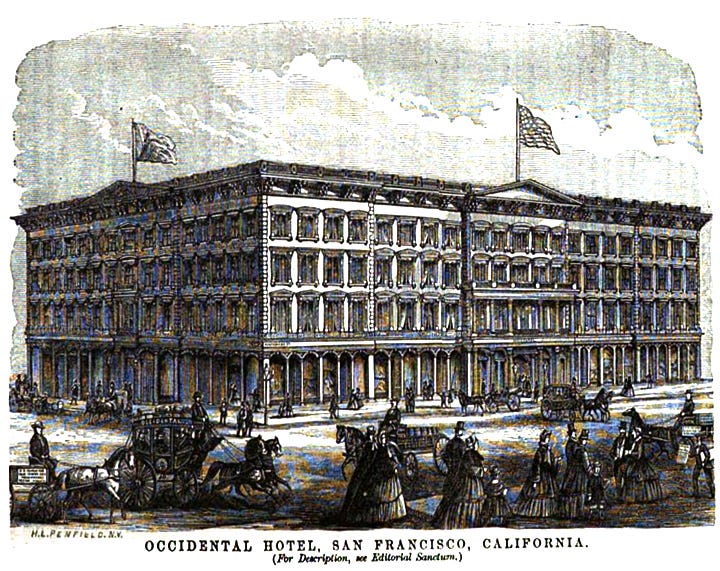

And he was in a state of high anticipation, as the Golden Era was to come out that day. Last month he had summoned the nerve to submit a poem to the journal, under a pseudonym. He’d paced for an hour on the street outside the sumptuous Occidental Hotel, where the Era was headquartered, before he got up the nerve to steal up the stairs to the newspaper office… and slip the sealed envelope into the ornate submissions box.

Today he would learn if his work had been accepted!

He was entirely unable to focus his mind, which even on less fraught days jumped from one thought to another so rapidly he despaired of keeping up with it. So he took up a feather duster and began to dust, his favorite way to look busy while letting his mind wander where it would.

Inevitably he concentrated his efforts on the items in window display… the better to view the enticing items outside the window, in the form of elegant men coming and going at the Lick House across the street.

Sometimes, to his delight, they crossed the walkway right in front of the window. Like this one, now. Dark-skinned, almost tropical-looking. And entirely oblivious to the smitten young clerk. Charlie pressed against the window pane, watching him wistfully until he turned the corner at the end of the block and disappeared, forever.

Until the next one, of course. San Francisco had no dearth of lovely youths.

But none that compared to those in the tropics.

Charlie had first encountered native boys at age eleven, when his family crossed Nicaragua on the long journey to California. The entire experience had been a sensual feast. The splashes of splendid colors. The oranges, great globes of delicious dew. The brilliantly exotic birds, scarlet plumage flickering like flame. Gigantic blossoms that might shame a rainbow.

And the natives. The glistening dark skin, adorned with little but feathers and necklaces and wreaths… the unabashed nudeness—

The bells on the door jangled, cutting short Charlie’s reverie.

He turned to the door to see a blond boy enter. A boy? No, a man. Short, slight, older than Charlie by some years, yet his face was untouched by the care lines of adulthood. Charlie’s heart began a rapid beat as he recognized him.

The Reverend Thomas Starr King.

Starr King spoke at every important celebration in the City. His sermons were an uplifting meld of politics and poetry, often printed whole in the newspapers. He was passionate. He was invincible. He was every bit the Starr of his name.

Charlie was a hero worshiper to the marrow. Starr King seemed to him the most heroic of them all. And now the young preacher was standing here before Charlie, like a holy vision.

“Hello?” Charlie squeaked.

The vision spoke. “Was it you who wrote this poem?” He lifted the journal he was holding. It was the Golden Era, folded back to a page. A page on which Charlie was stunned to see his own verse, signed by the pseudonym he’d chosen, Pip Pepperpod. Pip, of course, for Dickens’ child hero; Pepperpod because he adored alliteration.

“It’s mine,” he managed.

The minister responded by reading aloud—a voice made for poetry.

Love, maiden Love, cries not within the gates

Where sit the watchers, watching hour by hour;

Love hideth by the wayside and Love waits

Breathless within her bower.

Charlie felt his heart soar as he heard his words given new meaning by this exquisite being.

For faint her voice and very sweet to hear,

And dim her form, yet very fair to see,

O Love! my Love! it quiets all my fear

And hourly comforts me.

Who blindly loves, and boldly, he but errs;

Love answers not to each and all who cry;

Perchance this Love her willing love prefers

To those who pass her by.

They know not where to seek her and to find;

They wander after her from night till morn;

Their messages are wasted on the wind

And all in all forlorn.

Yet who shall lead the lover to his Love,

Or lead his Love to him, to ease his sigh?

No one I wot of out of Heaven above---

In sooth, not you, or I!

The Reverend turned his eyes up from the page. “If you don’t mind, I have added a few notes.” He started to hand Charlie the journal, but paused. “I hope you will not find them harsh. It is because you have strong powers and good capacities that I speak of blemishes more than excellences.”

Charlie took the extended newspaper from him in a daze, and their eyes met. “You write most soulfully,” the Reverend said warmly. “Let your soul guide you.”

Charlie’s heart stopped. He scarcely dared to hope. Could it be that he had found a kindred spirit?

Surely not. Starr King was married, with a family.

Starr King smiled at him, breaking the moment. “Perhaps you would attend my lecture series on American poetry.” He handed Charlie a slip of paper which he realized was a ticket. “And we shall talk further of your verses.”

He exited, leaving Charlie to rapturous reveries. The Reverend would take him under his wing. Not just as a protégé, but… dare he think it? A companion! He would read Charlie’s poetry at his lectures, they would work together on his sermons, they would tour the state together, and then the world… settling on an island… the islands…

Charlie hugged himself in sheer delight.

Was there a greater city on earth in which to dream?

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning: