Secessionist plots in Civil War San Francisco

After the Gold Rush, Chapter 34 - Asbury Harpending

Before and during the Civil War, powerful Southern forces (including the ruthless slaveholder Senator William Gwin from Mississippi, elected to “represent” California) were working to turn California into a slave state. When the war started, San Francisco business leaders and citizens were just becoming aware of the danger posed by the secretive Knights of the Golden Circle: secessionists in California who sought Confederate control over California and her wealth.

“With the city of San Francisco and her impregnable fortifications in Southern hands, the outward flow of gold, on which the Union cause will depend in a large measure, would cease—as a stream of water is shut off by turning a faucet.”

The following chapter is taken from Southern secessionist and convicted traitor Asbury Harpending’s autobiography:

The Great Diamond Hoax and Other Stirring Incidents in the Life of Asbury Harpending

Full book available at Project Gutenberg.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

After the Gold Rush, Chapter 34

1861: San Francisco, California

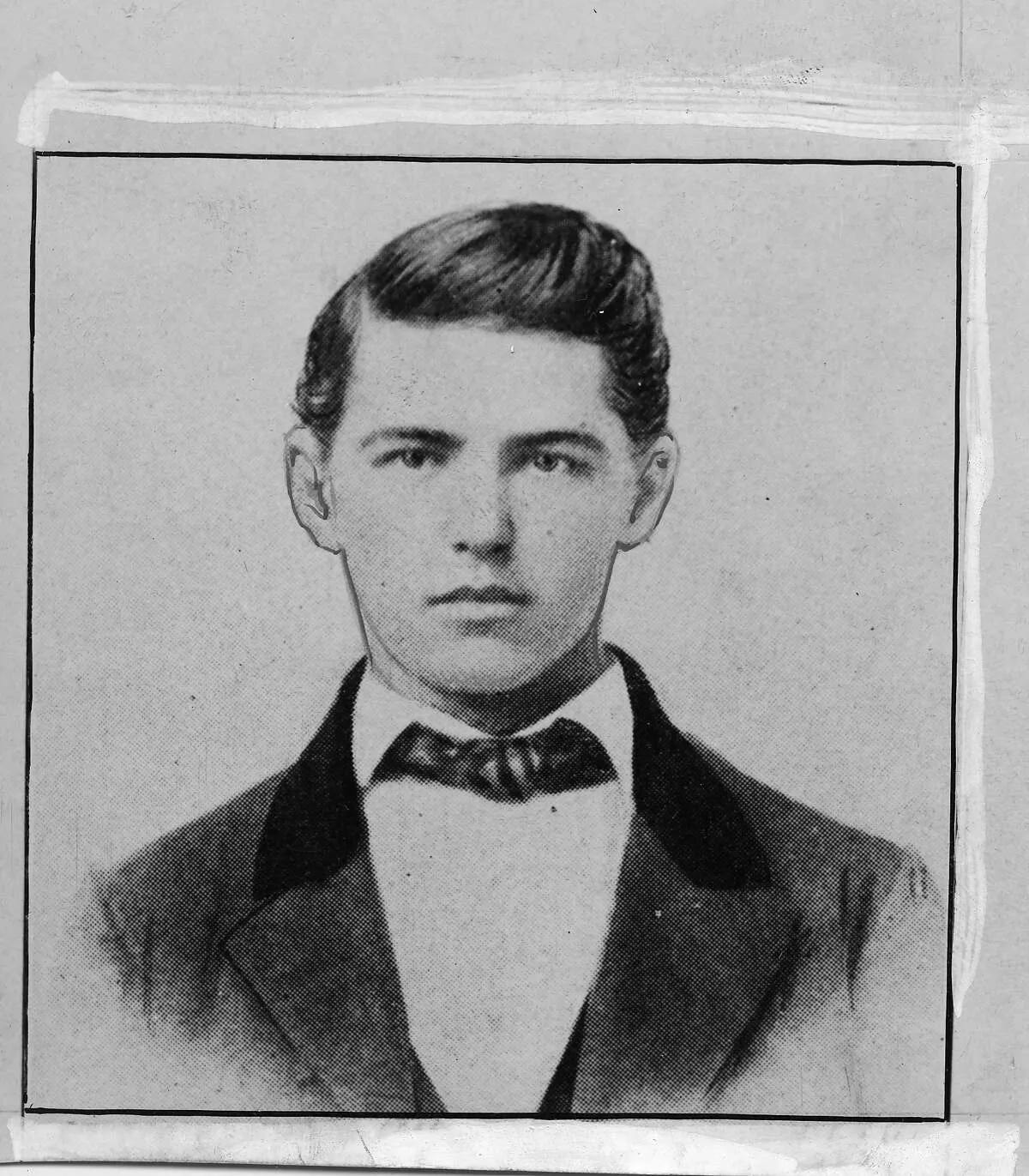

Asbury Harpending (age 22):

The Southern mind has a wonderful capacity for secret organization and for conducting operations on a vast scale behind a screen of impenetrable mystery. This would have a fine illustration in the workings of the Ku Klux Klan, in Reconstruction days, which destroyed carpet-bag rule and negro supremacy in the South and restored the government of the white race.

The operations of the Committee of Thirty of which I became a member demonstrated the same peculiar trait.

At every meeting of the Council of Thirty, the oath of secrecy was solemnly recited by all members in the name of the Southern States and upon our honor as Southern gentlemen, before proceeding to further business.

The organization was simplicity itself. We were under the absolute orders of a member whom we called “General,” and whose name everyone in the state would surely recognize. He called all the meetings by word of mouth, passed by one of the members. Anything in the way of writing was burned before the meeting broke up. The General received the large contributions in private, never drew a check, settled all accounts in gold coin and accounted to himself for the expenditure.

Each member was responsible for the organization of a fighting force of a hundred men. This was not difficult. California at that period abounded with reckless human material—ex-veterans of the Mexican war, ex-filibusters, ex-Indian fighters, all eager to engage in any undertaking that promised adventure and profit. Each member selected a trusty agent, or captain devoted to the cause of the South, simply told him to gather a body of picked men for whose equipment and pay he would be responsible, said nothing of the service intended, possibly left the impression that a filibuster expedition was in the wind.

These various bands were scattered in out-of-the-way places around the bay, ostensibly engaged in some peaceful occupation, such as chopping wood, fishing or the like, but in reality waiting for the word to act. Each member of the committee kept his own counsel. Only the General knew the location of the various detachments.

Our plans were to paralyze all organized resistance by a simultaneous attack. In California the Federal army was little more than a shadow. About two hundred soldiers were at Fort Point, less than a hundred at Alcatraz and a handful at Mare Island and at the arsenal at Benicia, where 30,000 stand of arms were stored.

Fort Mason, San Francisco: Civil War period

We proposed to carry these strongholds by a night attack and also seize the arsenals of the militia at San Francisco. With this abounding military equipment, we proposed to organize an army of Southern sympathizers, sufficient in number to beat down any unarmed resistance.

It was an opportunity absolutely within our grasp. At least thirty per cent of the population of California was from the South. The large foreign element was either neutral or had Southern leanings. We had already, under practical discipline, a body of the finest fighting men in the world, far more than enough to take the initial step with a certainty of success.

And those who might have offered an effective resistance were lulled in fancied security or indifferent.

The ties that bound the Pacific to the government at Washington were nowhere very strong. For all the immense tribute paid, the meager returns consisted of a few public buildings and public works.

Everything was in readiness. It only remained to strike the blow.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Why subscribe?

After the Gold Rush is a reader-supported publication. To receive a monthly roundup of new posts and support this work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Likes, Comments and Shares are extremely helpful and much appreciated!

Keep reading:

I am most fascinated by your work. This is history I've not been acquainted with; Thank you. *edit: And it occurs to me as I began to read on, that here again is mention of a 30 percent. Ironic...