“Frederick Douglass told Abe Lincoln, 'Give the black man guns and let him fight.'

And Abe Lincoln say, 'If I give him a gun, when it come to battle he might run.'

And Frederick Douglass say, 'Try him, and you'll win the war.'

And Abe said, 'All right, I'll try him.'"

- Cornelius Garner, Union soldier

"It is time for stronger remedies to be applied, in the form of hot lead and cold steel duly administered by 100,000 Black doctors."

- Abolitionist Wendell Phillips

July 17, 1862: San Francisco, California

The Executive Committee: J.J. Moore, Philip Alexander Bell, Peter Anderson, TMD Ward, Jeremiah B. Sanderson, James Madison Bell

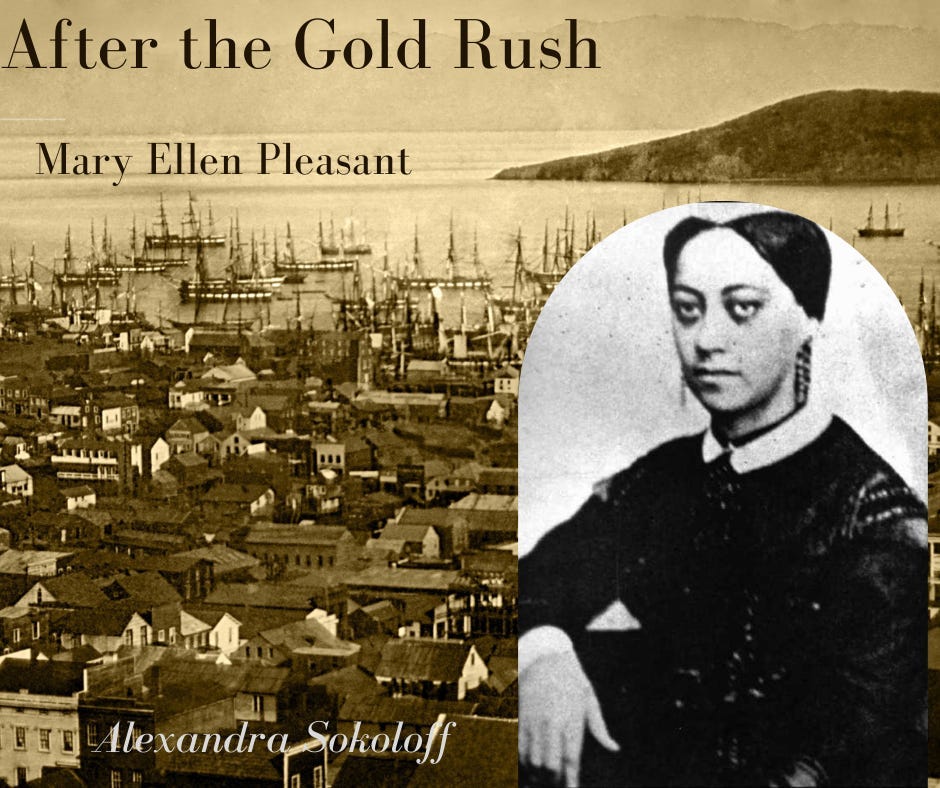

Mary Ellen Pleasant

I was invited again to the Executive Committee when it met to plan for a September celebration of the emancipation of slaves in the District of Columbia back in April. At the meeting we also discussed the news, which, as they say, was “mixed.”

It had been the gloomiest Fourth of July imaginable after a series of Union defeats.

Shiloh had been a Union success— strategically. But it was truly a shock to the country when those terrible casualty lists came out in the newspapers.

In the Seven Days Battles, McClellan’s Union Army of the Potomac invaded Virginia, but from June 25 to July 1, General Lee drove them away from Richmond and into retreat down the Virginia Peninsula. The Peninsula Campaign ended in defeat, crushing Northern morale while Southern spirits soared.

California chose to celebrate the Pacific Railroad Bill instead, with a grand torchlight demonstration of firemen in its honor.

Lincoln continued to resist enlisting Black soldiers. He told a delegation:

“To arm the negro would turn fifty thousand bayonets against us that were for us.”

But the horrific loss of Union men, eighteen thousand more souls in the Peninsula campaign, opened a door to press the issue. And it was heartening that Congress took the bit in its teeth. The Republicans, now in a majority, were far quicker than the President to act.

In June, Congress abolished slavery forever in the Western Territories.

On July 17, Congress passed The Second Confiscation Bill, emancipating all slaves in states engaged in rebellion, not just those engaged in the field or military services, in order to use all the physical force at the Union’s disposal.

I suppose they had to frame it as “confiscation” to get it passed, but that didn’t mean I liked it.

Everyone assumed that Lincoln would veto the bill, but he surprised us all and signed, with restrictions. There was no practical means of enforcement, but it worked—mostly because our people kept escaping in droves and showing up at Union encampments, ragged, starving—and ready to fight or work.

And the new Militia Act enrolled Negroes “in any military or naval service to which they may be found competent.” Black militias were already being raised in Louisiana, Kansas, and South Carolina.

We had eyes and ears in Washington, too. TMD Ward had written us:

“The President is making secret plans for an Emancipation Proclamation, while still trying to retain the loyalty of the border states.”

Peter Anderson was downright optimistic. “It shows his mind is changing.”

J.J. Moore nodded agreement. “And I believe the President is trying. He proposed compensation for gradual emancipation in the border states in March, and again in July.”

Philip Bell was less convinced. As usual, I was hanging back, listening rather than talking. But Bell brought up the very point I would have made: “And the border states refused, and Lincoln has not pressed the issue. And what if the border states secede to the South?”

Anderson immediately blustered, “None of us has a scrying ball—”

Bell didn’t even let him finish. “You know as well as I that the Union would be overwhelmed. We must win the war to win our freedom.”

J.J. stepped in to smooth things over. “It is strongly suspected that the President is waiting for a decisive Union victory to announce Emancipation.”

In fact, Lincoln moved sooner than we thought. He assembled his cabinet on July 22 to read them a draft of a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation that was far more radical than anything that he’d discussed before. There would be no cumbersome enforcement or gradual legislation. The Proclamation would set January 1, 1863, as the date on which all enslaved persons in states still in rebellion would be “thenceforth and forever free.”

It wasn’t about freedom. It was practical. It meant that massive workforce of Southern slaves, three and a half million of our people, would be instantly transferred from the Confederacy to the Union. It also only applied to the Confederate states, not the border states of Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky and Missouri. Lincoln intended to promise them they could keep their “property” if they stayed loyal to the Union.

To be fair, as far as I was willing to be, Lincoln was wrestling with a Cabinet and a country in which many white people, if not most, believed that our two races could not exist and thrive in social proximity. That equality meant the degradation and demoralization of the white race.

Lincoln’s own Attorney General Edward Bates said it straight out:

“I cannot imagine former slaves, fresh from the plantations of the South, where they have been long degraded by the total abolition of the family relation, shrouded in artificial darkness, and studiously kept in ignorance — living on an equal footing with whites.”

Personally, I couldn’t imagine former slave masters, fresh from the plantations of the South, where they have been long degraded by their own total lack of human feelings or Christian decency, living shrouded in the darkness of their own sin, deliberately basking in their own ignorance — ever living on an equal footing with Blacks.

The Committee could knock itself out trying to prove to inhuman people that we were human.

I was with Douglass on this one:

“Am I to argue that it is wrong to make men brutes, to rob them of their liberty, to work them without wages, to keep them ignorant of their relations to their fellow men, to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash, to load their limbs with irons, to hunt them with dogs, to sell them at auction, to sunder their families, to knock out their teeth, to burn their flesh, to starve them into obedience and submission to their masters?

Must I argue that a system thus marked with blood, and stained with pollution, is wrong? No! I will not. I have better employment for my time and strength than such arguments would imply.”

And so did I. I had my own businesses to run, my own work to do.

But in January, it happened. It really happened.

TheProclamation took effect on January first, 1863.

In San Francisco, a thousand Black Californians gathered in Platt’s Hall for the Grand Jubilee. By that day we’d had over a week to let it sink in, but it hadn’t.

Reverend Jeremiah B. Sanderson read the Proclamation to the crowd:

“That on the First Day of January in this year of Our Lord, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty-Three, all persons held as slaves within any state or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States then, thenceforward and forever free. And the Executive governments of this United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom."

I never felt anything so electric. We sang. We cried. We stood and quietly marveled.

Thenceforth and forever free.

I knew it was a limited document. I knew it didn't free as many slaves as the Second Confiscation Act had already legally set in motion.

It ended slavery only in secessionist states—and not in the slave power states that had remained in the Union or even in Southern states already under the control of the Union Army. Which meant almost half a million of our people were still enslaved.

But the President had kept his word, both the threat and the promise.

I stood with tears in my eyes as James Madison Bell read out a poem, The Progress of Liberty:

Never, in all the march of time,

Dawned on this land a more sublime

And grand event, than that for which

Today the lowly and the rich,

From thrice ten thousand altars, send

Their orisons to God, their friend.

The severance of the bondsman's chain;

The opening wide the prison door,

And ushering in this glorious reign

Of liberty, from shore to shore,

Has formed an epoch in the life

Of this great nation, that shall stand

And consecrate to sanguine strife,

The full redemption of the land.

During a break in the speeches, I saw J.J. Moore coming toward me with a teenager beside him. Maybe seventeen, tall, medium-skinned. They stopped in front of me and the boy kept his gaze down. But I’d seen him give me an appraising glance, a lighting flash of keen eyes as they’d approached.

“This is the lady I told you about.” J.J. was expansive on a regular day. Today he was exuberant. “We call Mrs. Pleasant ‘Black City Hall.’”

“Only when you want a favor,” I told him tartly. He knew I wasn’t likely to refuse him on a day like this, either.

He laughed heartily, and then put a hand on the young man’s shoulder.

“Mrs. Pleasant, this is James Allen.”

“How do you do, James?” I said, and waited.

He mumbled something that might have been, “Doin’ all right.”

I spoke sharply. “Eyes up. Shoulders straight. Look at me like the free man you are.”

He raised his chin and his eyes flashed murder. I saw the pride, there,

“Better. Now. Again. How do you do, James?”

His tone was perfect civility. “I’m well, ma’am, thank you. How does the day find you?”

I gave him a nod. “All right, then. Where’d you run from?” Wherever it was, he had to have left before Emancipation.

“Mississippi.”

It didn’t get much worse than that, for us. I knew what his smarts had cost him, and how deep he’d have learned to hide them.

“No more running,” J.J. said firmly. “For anyone.”

“I got him,” I said. I didn’t need J.J.’s interference, or his cheery outlook. There was work to do.

J.J. nodded to James. “I leave you in Mrs. Pleasant’s capable hands.” When he’d left, I turned back to the boy.

“What can you do?”

“Anything, ma’am.”

“What do you like to do?”

That lit his eyes up, and not in anger this time. “Horses. I’d rather work with horses than anything.”

“Good. That’s good. Give me a week, then come around and see me. The Reverend will tell you where. I know a man.”

“Yes, ma’am.” As he walked away, his step was more confident. Even jaunty. It was work we needed, not rosy daydreams. And the work was just starting.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

OMGosh, Alexandra!! This chapter alone is gold. THIS is the history we must teach to our citizens, of all ages!! I grew up in one of those border states... and never did we learn anything even remotely resembling the lessons you've taught, just in this golden chapter. Blessings to you and this novelized history.