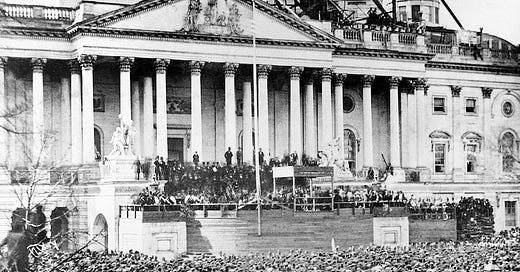

The inaugural address of President Lincoln inaugurates Civil War

After the Gold Rush, Chapter 31

The Inaugural Address of President Lincoln inaugurates Civil War. -Richmond Dispatch

March, 1861: San Francisco, California

Mary Ellen Pleasant:

I was catering a dinner at the Woodworths’ house on Minna the night the new Pony Express brought the text of Lincoln’s inaugural address to San Francisco.

Their guests included the Ralstons. Asbury Harpending was notably absent, having been banned from the house.

Selim Woodworth read Lincoln’s address out to his company at dinner.

Fellow-Citizens of the United States:

In compliance with a custom as old as the Government itself, I appear before you to address you briefly and to take in your presence the oath prescribed by the Constitution of the United States to be taken by the President before he enters on the execution of this office.

I do not consider it necessary at present for me to discuss those matters of administration about which there is no special anxiety or excitement.

Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that--

I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.

Those who nominated and elected me did so with full knowledge that I had made this and many similar declarations and had never recanted them; and more than this, they placed in the platform for my acceptance, and as a law to themselves and to me, the clear and emphatic resolution which I now read:

Resolved, That the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States, and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to that balance of power on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend; and we denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter what pretext, as among the gravest of crimes.

I now reiterate these sentiments, and in doing so I only press upon the public attention the most conclusive evidence of which the case is susceptible that the property, peace, and security of no section are to be in any wise endangered by the now incoming Administration. I add, too, that all the protection which, consistently with the Constitution and the laws, can be given will be cheerfully given to all the States when lawfully demanded, for whatever cause--as cheerfully to one section as to another.

There is much controversy about the delivering up of fugitives from service or labor. The clause I now read is as plainly written in the Constitution as any other of its provisions:

It is scarcely questioned that this provision was intended by those who made it for the reclaiming of what we call fugitive slaves; and the intention of the lawgiver is the law. All members of Congress swear their support to the whole Constitution--to this provision as much as to any other. To the proposition, then, that slaves whose cases come within the terms of this clause “shall be delivered up” their oaths are unanimous. Now, if they would make the effort in good temper, could they not with nearly equal unanimity frame and pass a law by means of which to keep good that unanimous oath?

There is some difference of opinion whether this clause should be enforced by national or by State authority, but surely that difference is not a very material one. If the slave is to be surrendered, it can be of but little consequence to him or to others by which authority it is done. And should anyone in any case be content that his oath shall go unkept on a merely unsubstantial controversy as to how it shall be kept?

All the men were immediately talking about how Lincoln may have saved the border states with his conciliatory speech.

I had to leave the room. I couldn’t listen to it.

Never mind all that horseshit about “the better angels of our nature.” Read the speech. He said flat out that he would “not interfere with slavery” and had “no inclination to do so.” That he would abide by the law that delivered up anyone who escaped chains back to those chains.

Frederick Douglass had said it: “Some thought we had in Mr. Lincoln the nerve and decision of an Oliver Cromwell, but the result shows we have merely a continuation of the Pierces and the Buchanans, who will grovel before the foul and withering curse of slavery.”

No. “Honest Abe” Lincoln was no friend to me or mine.

Through my rage, I felt someone behind me. I turned, too fast. In the doorway was the new Mrs. Woodworth.

Lizzie Ralston had introduced them. It had been a brief courtship and a quick marriage, Selim Woodworth knowing he would be called to battle any time, now.

Lisette spoke quietly. “I’m sorry.”

“For what?” I could hear the ice in my voice. Careful, I told myself. My protégé was now a powerful, important ally. I needed to keep her on side.

Lisette met my eyes. “I am sorry that men are not braver.”

And as it turned out, conciliation got Lincoln exactly nowhere.

Jefferson Davis issued a call for 100,000 men from the states’ militias to defend the new Confederacy, and instructed the militias to take possession of Federal institutions inside the Confederacy: all the courts, post offices, arsenals and forts.

Even as Lincoln called up 75,000 troops to reoccupy Federal properties throughout the South, the CSA had seized every Federal building in every Southern state.

Go on to Chapter 32:

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning: