Women's History Month: Jane Stanford

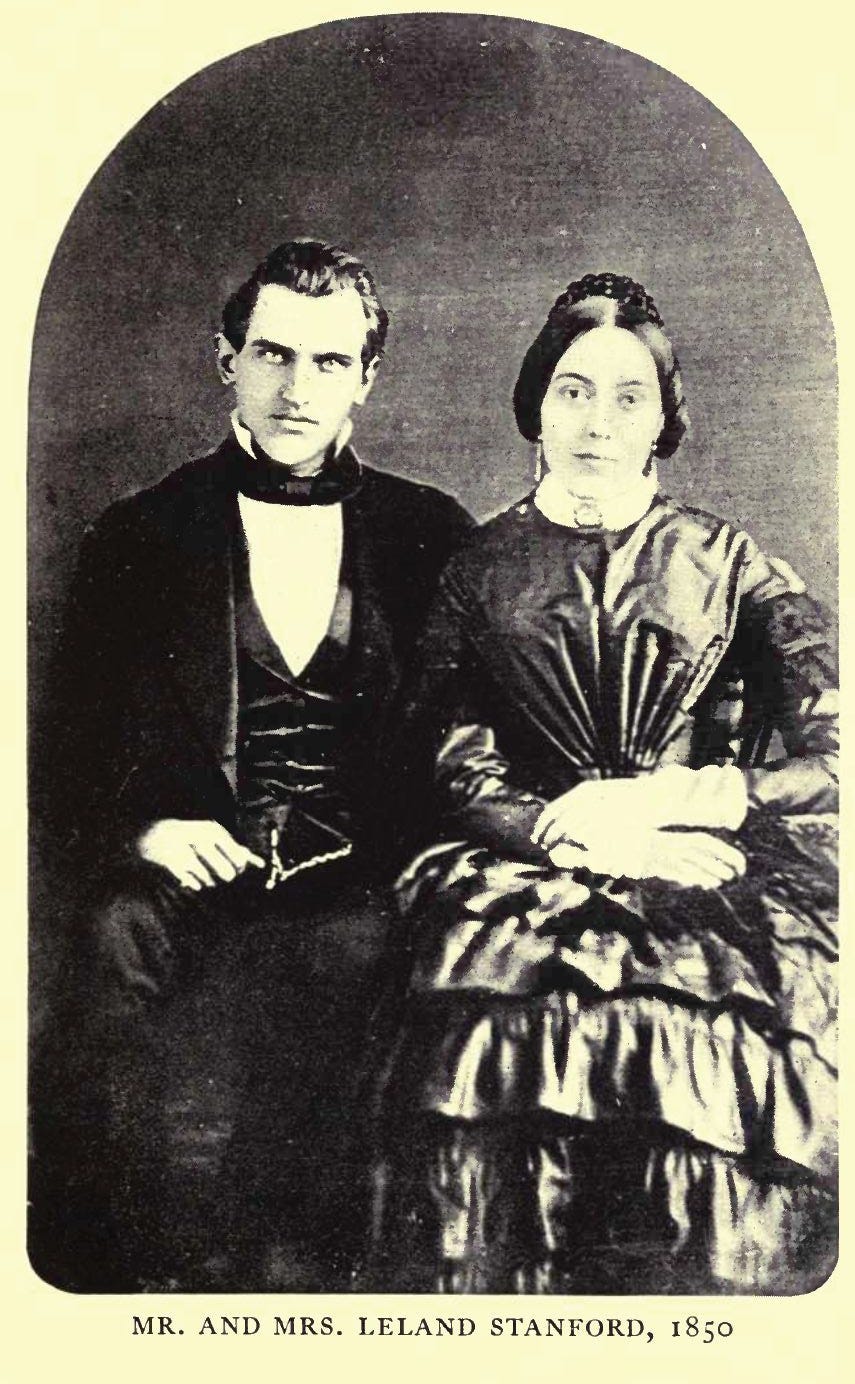

JANE STANFORD (1828-1905). Co-founder and benefactor of Stanford University. Wife of railroad baron, California governor and US Senator Leland Stanford.

I want to be really clear: Jane and Leland Stanford were deeply problematic people. She is not by any means any kind of heroine to me. But I find her fascinating. As with all women of the time, her just surviving the times (including the treacherous journey West, before the transcontinental railroad that her husband would help build) was a miracle in itself.

They were a struggling couple in pioneer Sacramento but Leland quickly rose in the ranks of the brand new Republican Party to become California governor. He was anti-slavery, a staunch supporter of Lincoln—while his inaugural speech was a horror of anti-Chinese racism. But simultaneously Jane had a loving and maternal relationship with their Chinese houseboy, Moy Jin Mun. Her (in her mind) much more attractive husband was devoted to her all their lives, and gave her every luxury: mansions, jewels, travel—that his wildly unscrupulous unfettered capitalism and political offices and influence made them well able to afford.

She longed throughout their marriage for a child and finally conceived at age 39 (very rare for the day), apparently with help from some insemination technology from the veterinarian who bred Leland’s prize racehorses. You go, Jane!

The child that resulted, Leland Stanford Jr.. was the center of his parents’ world and showed early mechanical and archeological talents. But tragically, on his first trip to Europe with his parents he contracted and died of typhoid fever. He was just 15 years old.

His grieving father reported having a vision that Leland Jr. appeared to him and urged his parents to found a university. Leland threw himself into the project, but didn’t live to complete it. It was Jane who had to fight to get Stanford built and kept open in its early days. Excellent, yeah—but she undercut the achievement by limiting enrollment of women, fearing her son’s name would be diminished by attachment to a mere women’s college. (Jane’s friend Phoebe Hearst, a key benefactor of U.C. Berkeley, did the opposite: creating academic opportunity and housing for Berkeley’s female students.)

To cap off a conflicted and incredible life, Jane was murdered during a trip to Hawaii—a case that remains a mystery to this day.

Meet Jane Stanford:

AFTER THE GOLD RUSH: Chapter 44

January 1862, Sacramento California

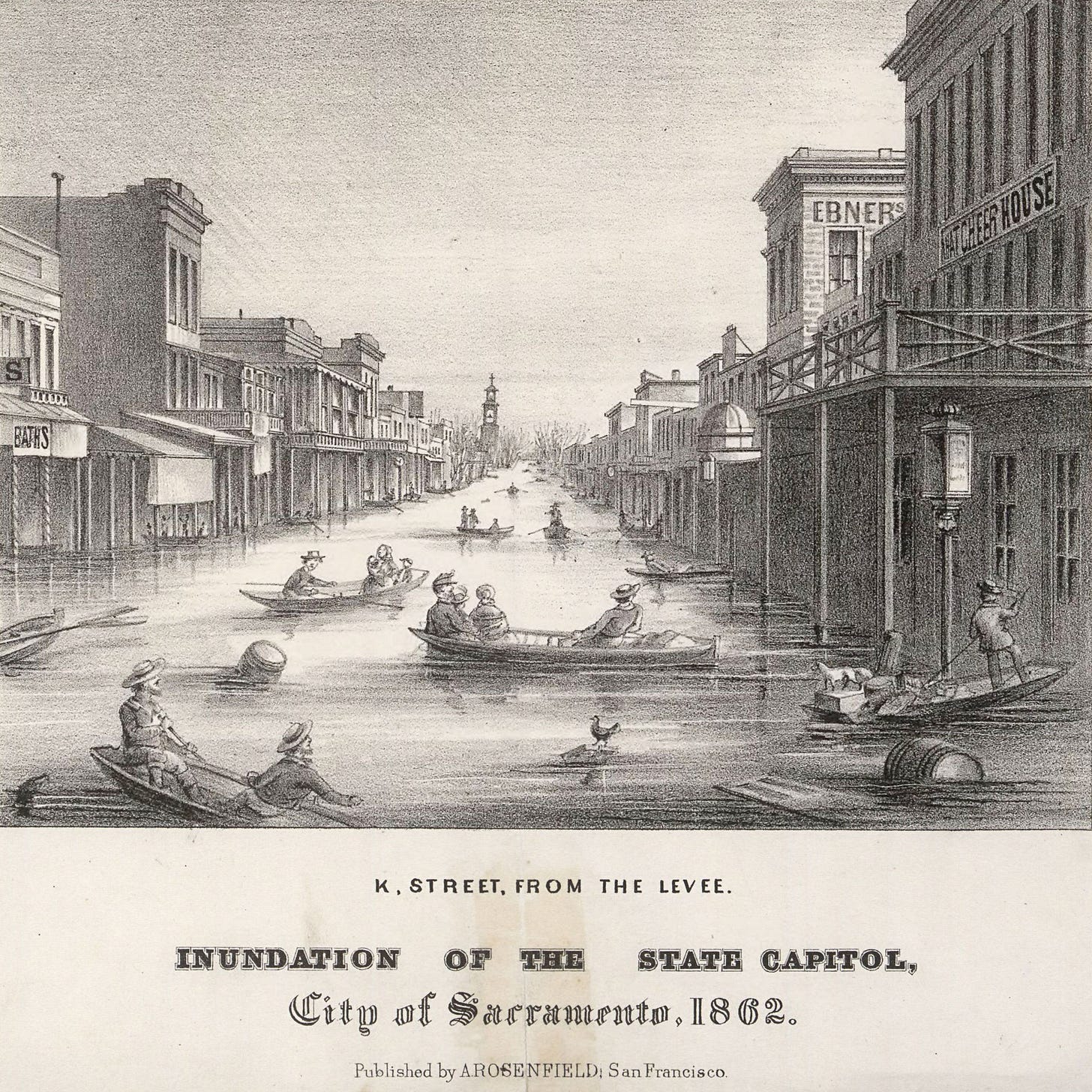

The Great Sacramento Flood

Leland and Jane Stanford (age 38 and 34)

Moy Jin Mun (15)

Moy Jin Kee (18)

Jane Stanford looked out her bedroom window at a downpour.

The rain didn’t so much fall as crash down in solid sheets. The whole yard of the mansion, their brand-new home, was a lake.

There had been fifty inches of rain in San Francisco that winter, a staggering thirty more than the average. It transformed the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys into an inland sea, two-hundred fifty to three hundred miles long and twenty to sixty miles wide, drowning thousands of head of livestock. Cows, pigs, and sheep routinely floated past the house, dead and alive. Farming, transportation and business were at a standstill.

She became vaguely aware of someone below her calling her name, and turned her eyes downward, out the window.

The road in front of the house had become a virtual river, rising to the porch steps. On that river beside their front steps, Leland sat in a rowboat.

“Jennie!” He waved to her, beckoning her down.

It was the long-awaited day of Leland’s inauguration. She was hours away from becoming Mrs. Governor Stanford.

But today, the only way to reach the legislature was by boat.

“Very beautiful, Mrs. Jane,” a young voice spoke behind her.

A slim, graceful Chinese boy of fifteen, her houseboy Moy Jin Mun, stood in the doorway waiting for her.

She caught a glimpse of herself in the oval mirror, dressed in velvet and lace… and plain as ever.

“Thank you, Jin Mun,” she replied to the boy.

Jin Mun escorted her downstairs. In the front hallway he helped her on with a velvet cloak, then another older, dispensable one. He opened the door, raised a large umbrella to walk her across the porch and down the steps, where Leland and the rowboat were waiting in the rain.

Her lower body was drenched within seconds, and her legs had to fight against her sodden dress and crinoline. The rain was a roar in her ears. She felt Jin Mun’s hand under her elbow, holding her steady, helping her along.

Before them, the river roiled where there had been no river before.

Her husband stood to hand her into the rowboat. Once she was securely seated, Leland, the incoming Governor of California, took his own precarious seat and began to row down the road.

Jin Mun returned to the sheltered porch, and stood with his elder brother Moy Jin Kee, watching the Stanfords row away.

The brothers had grown up in Xinning, in the Pearl River Delta region in Guangdong province of China. The Tai Ping Rebellion had commenced a wave of Chinese immigration to America, mostly men in their teens and twenties looking both to escape political chaos and to seek their fortune on Gam Saan: “Gold Mountain.”

Like many Chinese parents of mid-range economic status, the Moys’ parents had gathered the funds for transportation in steerage, and sent their boys to America.

White miners bitterly resented the growing presence of the Chinese. No sooner had the Moys arrived in the gold fields near Sacramento, then the state had passed laws prohibiting Chinese from gold mining,

But Jin Kee found work as a cook in a Sacramento restaurant, and proved to be an excellent chef. There he had caught the attention of Leland Stanford. Cooking brought a premium price in good households. But the job entailed far more than cooking. The Chinese “chef” was often in charge of all household management: buying, hiring, animal tending, building maintenance. Jin Kee was able to bring his younger brother along to the Stanford home with him, and serving as houseboy, Jin Mun quickly become a favorite of Mrs. Jane.

The Stanford farmhouse was unbelievable luxury compared to their lives in China and the mining camps, and the Moys’ wages were enough to send home to their parents with some to spare.

Jin Mun found Mrs. Jane strange, but kind. She lived in her own ethereal world, and Jin Mun, having been raised with the constant presence of ancestral spirits, found that a comfort in the unfamiliar and bewildering Lo Fan society.

Beside him, Jin Kee had been silently studying the sky. Now he said,

“The rain will not stop tonight.”

Jin Mun looked at his brother, unnerved. The whole Sacramento Basin was an ocean. How much more water could there be?

Jin Kee answered the unvoiced question. “Mining has destroyed the forests and hills that protect these valleys. There is nothing left to stop the water.”

He looked down at the river below the steps. Jin Mun followed his brother’s gaze, and his pulse jumped. In the time since Mrs. Jane had departed, the water had risen to cover the bottom step.

Jin Kee turned, and ordered his brother, “Take your things from our rooms and put them in the attic. We move everything of value up from the first floor today.”

In the state assembly chamber, Jane sat in her place of honor beside the podium, watching her husband address the crowd.

He read almost painfully slowly from a prepared speech. It was Leland’s way: steady and ponderous. But Jane knew his deliberate manner impressed onlookers as being thoughtful. His very stiffness seemed to impress the crowd as sincerity, a reassuring change from more glib, extemporaneous speakers.

Jane had little interest in Leland’s speech. She was engaged in thoughts of her own.

This will show them, she thought. Those vile women in Albany who’d whispered that her handsome husband had abandoned her, those three long years when he’d first taken the journey to California.

But Leland had come back for her, as he’d always promised he would. And look, now.

“Mrs. Governor Stanford,” she whispered fiercely.

She smoothed the fine silk of her dress, forced herself to concentrate, to listen to Leland’s words.

“To my mind it is clear, that the settlement among us of an inferior race is to be discouraged by every legitimate means. Asia, with her numberless millions, sends to our shores the dregs of her population. Large numbers of this class are already here, and unless we do something early to check their immigration, the question, which of the two tides of immigration, meeting upon the shores of the Pacific, shall be turned back, will be forced upon our consideration, when far more difficult than now of disposal. There can be no doubt but that the presence among us of numbers of degraded and distinct people must exercise a deleterious influence upon the superior race, and to a certain extent, repel desirable immigration.”

Leland paused to receive the vigorous applause from the state assembly chamber.

Jane smiled through all the reception and the speeches and toasts. Alas, they could not stay long to enjoy the celebration. The watery journey home would be too dangerous after dark.

Late that afternoon, Leland handed her into the rowboat. As he took up the oars, she said, “Governor.”

He looked at her, beaming. And then she finished, “I believe I should like to adopt Jin Mun.”

Leland took a long moment before he answered. It was his way.

“A splendid idea, Jennie. We shall look into the particulars.”

When Leland rowed the boat past a clump of trees into the flooded corridor of their farmland, Jane squinted ahead, and thought the cordial she had drunk at the reception must have toyed with her mind.

She could see nothing in the valley but that lake of water, and the tops of trees.

“Where is the house?” she asked. Her voice seemed to come from a great distance.

Then she fixed her gaze on a one-story building sticking forlornly out of the lake. With a jolt of horror, she recognized the second floor of their house. The entire bottom story was now underwater.

Leland rowed up to the building, and had to hold the boat steady for Jane to boost herself up on the window frame of their bedroom. She pulled up her skirts, threw a leg over the sill and managed to drag herself through the window.

In the bedroom, she stood up, gasping, water pouring from her sodden dress…

… and twisted around at a strange lowing sound behind her.

A cow stood beside their bed. It looked as aghast to see her as she was to see it.

She stared into its brown eyes. “Mercy,” she said weakly.

After the Gold Rush is a reader-supported publication. Subscribe for free to receive new posts!