Ambrose Bierce and Asbury Harpending at the Battle of Shiloh

California History After the Gold Rush

The journalist and author Ambrose Bierce would not make it to California until 1865, where he would become known as “The Wickedest Man in San Francisco” for his scathing sendups of the wealthy and powerful. Before his journalism and anti-railroader activism, he was a decorated Union officer and passionate abolitionist. His most poignant writing is his incredibly, sensually realistic depictions of his Civil War battlefield experiences.

Asbury Harpending was Bierce’s polar opposite: the son of a Southern plantation holder and unapologetic secessionist and slave holder who during the Civil War made multiple attempts to hijack shipments of gold moving sailing from San Francisco to Union coffers, and was part of a failed conspiracy to overthrow San Francisco’s Presidio to take its immense cache of armaments for the Confederacy.

These two fascinating characters of San Francisco history both took part in the Civil War Battle of Shiloh. I’ve put together excerpts from their separate accounts of the battle, which mesh to provide an account of the battle from both Confederate and Union perspectives.

Read AFTER THE GOLD RUSH from the beginning:

-AFTER THE GOLD RUSH, Chapter 47

March 1862

Acapulco, Mexico—Richmond, Virginia

Asbury Harpending:

I was broken-hearted at the turn of affairs in California. Needless to say, I was one of those who voted “yes” on the memorable night when the Committee of Thirty (secessionist traitors operating in San Francisco) disbanded. News of our Senator Gwin’s arrest was another blow.

But the Chivalry soon rallied.

The idea of interrupting the gold shipments by the Pacific Mail, very essential to the government at Washington, again took form. This was to be effected by seizure on the high seas. A number of prominent men were interested and I was requested to become one.

I had no stomach for downright piracy, though ready for any risk. I stipulated that I must first receive a regular commission from the Confederate Navy. This being agreed to, the sum of $250,000 was subscribed, of which $50,000 was mine.

In company with H. T. Templeton, a well-known Californian, later a familiar of the Crocker family, we traveled by steamer to Acapulco. Mexico was then in an uproar over the French invasion. The American Consul, a son of John A. Sutter, advised us that it was little short of madness to cross the country to Mexico City, which we gave as our destination. But Templeton was brave as a lion and I was young, reckless and confident in my luck. Heavily armed, with a single guide—who, by the way, fled in terror at the first sight of danger—we set out on a venturesome journey.

We had several pitched battles with small bands of “ladrones” or robbers. Once both our horses were shot from under us. My previously acquired knowledge of Spanish stood us in good stead in securing fresh equipment, knowledge of the way and sometimes hospitality and shelter. Finally, after great hardships and danger we reached Mexico City, and thence proceeded without incident to Vera Cruz, which was a sort of rendezvous for blockade runners. Here Templeton and I parted company with mutual regrets.

I boarded a blockade runner and during a rainy night we slipped past the Federal warships into Charleston.

I had no difficulty in reaching Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. It was a vast, hustling, military camp. Troops were marching and counter-marching, officers on horseback dashing to and fro on mysterious missions and everywhere the atmosphere of war.

It was a couple of days before I saw President Jefferson Davis. I laid my plans before him, to his great interest, and later we had several interviews.

He fully realized the importance of shutting off the great gold shipments to the East from California. President Davis said it would be more important than many victories in the field. At the same time, he saw grave difficulties in the way. He did not believe that a vessel could be outfitted for the purpose in any of the Pacific ports without arousing suspicion, disclosure and capture. He warned me that my associates and myself were taking an awful risk, almost sure to result in ultimate disaster. Moreover, he was uncertain whether under any circumstances the enterprise could be justified under international law and whether the proceeding would not fall under the head of piracy, against which he resolutely set his face.

All these questions were submitted to one of his Cabinet officers, Judah P. Benjamin. Mr. Benjamin was of Jewish ancestry and one of the ablest men who guided the way of the Confederacy. This distinguished gentleman examined with great care the questions involved, particularly on the piracy point, and he gave an opinion that it would be entirely within the scope of international law to equip and sail a vessel out of any port of the United States provided no overt act against commerce were committed before a foreign port was reached, letters of marque exhibited there and the open purpose of those in command declared. So for what followed I had at least the advice of eminent counsel.

While I was waiting for Davis’s decision, the Confederate cause seemed at its zenith in Richmond. Everywhere was abounding confidence in the final result. And now came a whisper that a great battle would soon be fought that ought to be decisive.

I was eager to see something of the war game and with letters from the Secretary of War, hurried westward, arriving at Corinth, Mississippi, on April 4, 1862. Here a small Confederate army was assembled under General Albert Sidney Johnston, the same Johnson as of my Presidio experience. Nine miles away, General Grant was encamped at Shiloh with 35,000 men, confidently awaiting the arrival of General Buell with 30,000 more, to begin the invasion of the South.

At the risk of criticism by experts I am going to tell briefly what a great, old-fashioned battle seemed like to a raw looker-on.

April 4, 1862: Shiloh, Tennessee

When I arrived in Corinth on April 4, 1862, not more than five thousand men were assembled there. But all that night and the next day troop trains were unloading enormous reinforcements and some were arriving by forced marches on foot. By the night of April 5, between twenty-five and thirty thousand soldiers were in camp, the flower of the fighting army of the South. General Albert Sidney Johnston, with his heroic figure and magnetic presence, roused the men to a height of martial exultation very hard to describe. Everyone knew that a great battle was impending. Most of them guessed that the morrow would be the day. But they hardly seemed able to wait. They were like war dogs tugging at the leash, confident in themselves, confident in their cause. One would have thought they were bound for a holiday excursion instead of a death grapple from which many would never emerge.

Very much to my disappointment, I was assigned to the staff of General Beauregard, second in command. I had hoped to be with General Johnston, where the fighting would be the fiercest. Nevertheless, I had enough.

The troops retired at an early hour on the night of April 5. But in the darkness flitted shadows of alert men, making busy preparations for a great event. At two o’clock in the morning, the troops were roused from their sleep, had hasty refreshment in the darkness, and then fell in, company after company, like so much clock work, and the march to Pittsburg Landing, or Shiloh, nine miles away, began. The infantry was well in front, separated by perhaps half a mile from the artillery and more noisy equipment.

The nature of the country was admirable for a secret movement. It was well wooded, with abundant cover to screen our presence, and it seemed almost uncanny how the thousands of men marched forward with scarce noise enough to stir the early morning air. Not a word was spoken.

Suddenly before us lay the army of General Grant. It seems to me that it was not more than two hundred yards away. Breakfast was being cooked, the officers and men totally off their guard.

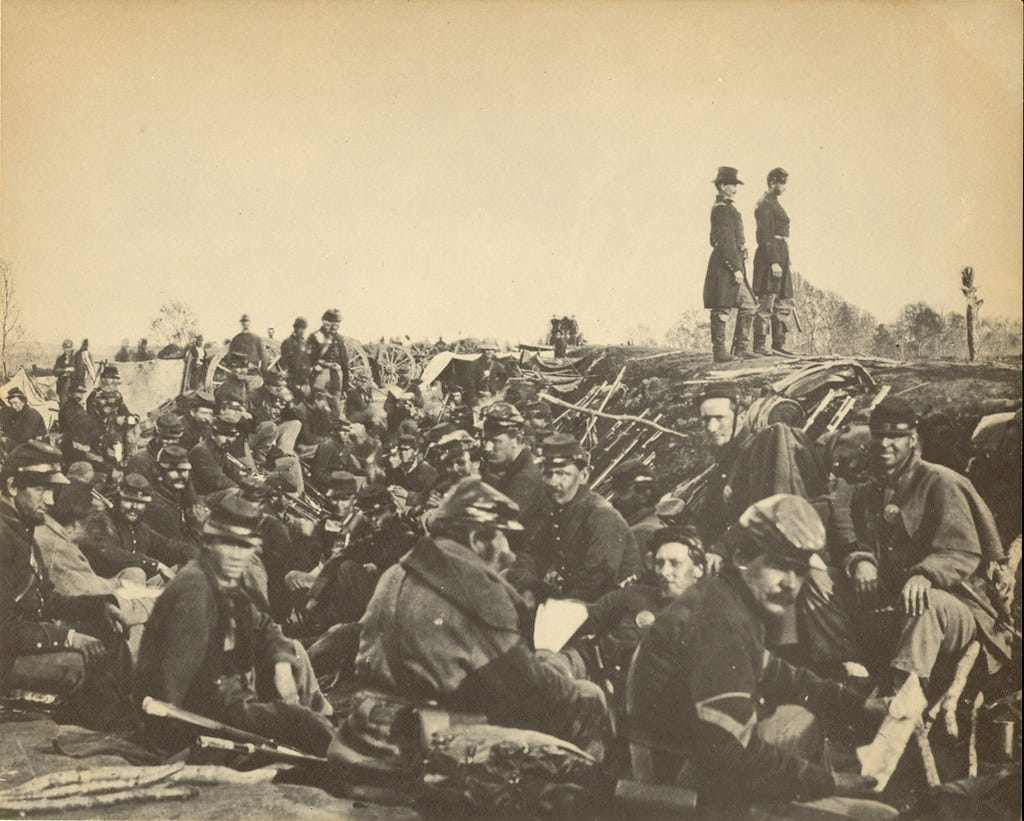

Union encampment, Shiloh, Tennessee

Ambrose Bierce

The morning of Sunday, the sixth day of April, 1862, was bright and warm. Reveille had been sounded rather late, for the troops, wearied with long marching, were to have a day of rest.

The men were idling about the embers of their bivouac fires; some preparing breakfast, others looking carelessly to the condition of their arms and accouterments, against the inevitable inspection; still others were chaffing with indolent dogmatism on that never-failing theme, the end and object of the campaign. Sentinels paced up and down the confused front with a lounging freedom of mien and stride that would not have been tolerated at another time. A few of them limped unsoldierly in deference to blistered feet.

At a little distance in rear of the stacked arms were a few tents out of which frowsy-headed officers occasionally peered, languidly calling to their servants to fetch a basin of water, dust a coat or polish a scabbard. Trim young mounted orderlies, bearing dispatches obviously unimportant, urged their lazy nags by devious ways amongst the men, enduring with unconcern their good-humored raillery, the penalty of superior station. Little negroes of not very clearly defined status and function lolled on their stomachs, kicking their long, bare heels in the sunshine, or slumbered peacefully, unaware of the practical waggery prepared by white hands for their undoing.

Presently the flag hanging limp and lifeless at headquarters was seen to lift itself spiritedly from the staff. At the same instant was heard a dull, distant sound like the heavy breathing of some great animal below the horizon. The flag had lifted its head to listen.

There was a momentary lull in the hum of the human swarm; then, as the flag drooped the hush passed away. But there were some hundreds more men on their feet than before; some thousands of hearts beating with a quicker pulse.

Again the flag made a warning sign, and again the breeze bore to our ears the long, deep sighing of iron lungs. The division, as if it had received the sharp word of command, sprang to its feet, and stood in groups at "attention." Even the little blacks got up.

I have since seen similar effects produced by earthquakes; I am not sure but the ground was trembling then. The mess-cooks, wise in their generation, lifted the steaming camp-kettles off the fire and stood by to cast out.

Asbury Harpending

Nothing in the nature of surprise could be imagined more terrible and complete. Quick commands were given, there was a rattle of musketry, the “rebel” yell rang out—a sound that might well start the resurrection of the dead—and the next instant I saw what appeared a long line of racing apparitions in gray, with fixed bayonets, clear the intervening space and fall like a cloudburst on the men in blue. The mounted orderlies had somehow disappeared. Officers came ducking from beneath their tents and gathered in groups. Headquarters had become a swarming hive.

Ambrose Bierce

The sound of the great guns now came in regular throbbings—the strong, full pulse of the fever of battle. The flag flapped excitedly, shaking out its blazonry of stars and stripes with a sort of fierce delight.

Toward the knot of officers in its shadow dashed from somewhere—he seemed to have burst out of the ground in a cloud of dust—a mounted aide-de-camp, and on the instant rose the sharp, clear notes of a bugle, caught up and repeated, and passed on by other bugles, until the level reaches of brown fields, the line of woods trending away to far hills, and the unseen valleys beyond were "telling of the sound," the farther, fainter strains half drowned in ringing cheers as the men ran to range themselves behind the stacks of arms. For this call was not the wearisome "general" before which the tents go down; it was the exhilarating assembly, which goes to the heart as wine and stirs the blood like the kisses of a beautiful woman.

Who that has heard it calling to him above the grumble of great guns can forget the wild intoxication of its music?

Asbury Harpending

Anyone could see the line of General Johnston’s strategy. Grant’s army was encamped on rising ground beyond the Tennessee. Behind it the ground fell off rather abruptly to a narrow plain along the river bank, beyond which was no retreat.

The object of the attack was to force the Federal line to the river bank and then drive in the wings until the Union army became a huddled mass on the low ground where it could not fight effectively, and be at the mercy of artillery fire. Then it must either surrender or be wiped out.

The first step was accomplished by the initial bayonet charge. The second required more time.

Ambrose Bierce

In front of our brigade the enemy's line ran through open fields along a slight crest. At each end of this open ground we were close up to him in the woods, but the clear ground we could not hope to occupy until night, when darkness would enable us to burrow like moles and throw up earth. At this point our line was a quarter-mile away in the edge of a wood. Roughly, we formed a semicircle, the enemy's fortified line being the chord of the arc.

The picture was intensely dramatic, but in no degree theatrical. Successive scores of rifles spat at us viciously, and our own line in the edge of the timber broke out in visible and audible defense. No longer regardful of themselves or their orders, our fellows sprang to their feet, and swarming into the open sent broad sheets of bullets against the blazing crest of the offending works, which poured an answering fire into their unprotected groups with deadly effect. The artillery on both sides joined the battle, punctuating the rattle and roar with deep, earth-shaking explosions and tearing the air with storms of screaming grape, which from the enemy's side splintered the trees and spattered them with blood, and from ours defiled the smoke of his arms with banks and clouds of dust from his parapet.

Asbury Harpending

Nothing saved the army of General Grant from utter destruction but the presence of several gunboats in the Tennessee river. These were splendidly handled, and the fire was deadly and precise. It gave the Union forces an opportunity to recover somewhat and put up a gallant fight. Field artillery was concentrated on the gunboats. Sharpshooters climbed into nearby trees and picked off the gunners at their posts.

The fire became less frequent, less precise. The battle raged into the afternoon.

The field was covered with dead and dying, but the strategy of General Johnston was rapidly bearing fruit.

Ambrose Bierce

As darkness fell, we attempted to take the field. Inch by inch we crept along, treading on one another’s heels by way of keeping together. Commands were passed along the line in whispers; more commonly none were given. When the men had pressed so closely together that they could advance no farther they stood stock-still, sheltering the locks of their rifles with their ponchos. In this position many fell asleep. When those in front suddenly stepped away those in the rear, roused by the tramping, hastened after with such zeal that the line was soon choked again. Evidently the head of the division was being piloted at a snail’s pace by some one who did not feel sure of his ground. Very often we struck our feet against the dead; more frequently against those who still had spirit enough to resent it with a moan. These were lifted carefully to one side and abandoned. Some had sense enough to ask in their weak way for water. Absurd! Their clothes were soaken, their hair dank; their white faces, dimly discernible, were clammy and cold. Besides, none of us had any water.

There was plenty coming, though, for before midnight a thunderstorm broke upon us with great violence. The rain, which had for hours been a dull drizzle, fell with a copiousness that stifled us; we moved in running water up to our ankles. Happily, we were in a forest of great trees heavily “decorated” with Spanish moss, or with an enemy standing to his guns the disclosures of the lightning might have been inconvenient. As it was, the incessant blaze enabled us to consult our watches and encouraged us by displaying our numbers; our black, sinuous line, creeping like a giant serpent beneath the trees, was apparently interminable.

I am almost ashamed to say how sweet I found the companionship of those coarse men.

So the long night wore away, and as the glimmer of morning crept in through the forest we found ourselves in a more open country. But where?

Not a sign of battle was here. The trees were neither splintered nor scarred, the underbrush was unmown, the ground had no footprints but our own. It was as if we had broken into glades sacred to eternal silence. I should not have been surprised to see sleek leopards come fawning about our feet, and milk-white deer confront us with human eyes.

A few inaudible commands from an invisible leader had placed us in order of battle. But where was the enemy? Where, too, were the riddled regiments that we had come to save? Had our other divisions arrived during the night and passed the river to assist us? or were we to oppose our paltry five thousand breasts to an army flushed with victory? What protected our right? Who lay upon our left? Was there really anything in our front?

There came, borne to us on the raw morning air, the long, weird note of a bugle. It was directly before us. It rose with a low, clear, deliberate warble, and seemed to float in the gray sky like the note of a lark. The bugle calls of the Federal and the Confederate armies were the same: it was the “assembly”!

As it died away I observed that the atmosphere had suffered a change; despite the equilibrium established by the storm, it was electric. Wings were growing on blistered feet. Bruised muscles and jolted bones, shoulders pounded by the cruel knapsack, eyelids leaden from lack of sleep—all were pervaded by the subtle fluid, all were unconscious of their clay. The men thrust forward their heads, expanded their eyes and clenched their teeth. They breathed hard, as if throttled by tugging at the leash.

If you had laid your hand in the beard or hair of one of these men it would have crackled and shot sparks.

Then – I can’t describe it – the forest seemed all at once to flame up and disappear with a crash like that of a great wave upon a beach – a crash that expired in hot hissing, and the sickening “spat” of lead against flesh. A dozen of my brave fellows tumbled over like ten-pins. Some struggled to their feet, only to go down again, and yet again. There was a very pretty line of dead continually growing in our rear, and doubtless the enemy had at his back a similar encouragement.

Asbury Harpending

The gunboats were almost silenced, the Federal columns showed apparent signs of disintegration. Another hour would have seen a total rout. General Johnston had been everywhere, the directing genius, exposing himself to needless dangers.

Just in the moment of triumph, he fell headlong from his horse.

It seemed as if the news of this irreparable loss spread through the army like wildfire and caused, not a demoralization, but a general pause. Beauregard took command, evidently under a great mental strain. To the surprise of many, he gave orders to retire. I heard him say: “To-morrow we will be across the Tennessee river, or in hell.”

He had another guess. Early the next morning Union General Buell crossed the Tennessee with thirty-five thousand fresh troops, and all day we were fighting our way back to the strong position at Corinth.

The great opportunity was lost.

Ambrose Bierce

As matters stood, we were now very evenly matched, and how long we might have held out God only knows. But all at once something appeared to have gone wrong with the enemy’s left; our men had somewhere pierced his line. A moment later his whole front gave way, and springing forward with fixed bayonets we pushed him in utter confusion back to his original line.

Here, among the tents from which Grant’s people had been expelled the day before, our broken and disordered regiments inextricably intermingled, and drunken with the wine of triumph, dashed confidently against a pair of trim battalions, provoking a tempest of hissing lead that made us stagger under its very weight. The sharp onset of another against our flank sent us whirling back with fire at our heels and fresh foes in merciless pursuit—who in their turn were broken upon the front of the invalided brigade previously mentioned, which had moved up from the rear to assist in this lively work.

As we rallied to reform behind our beloved guns and noted the ridiculous brevity of our line—as we sank from sheer fatigue, and tried to moderate the terrific thumping of our hearts—as we caught our breath to ask who had seen such-and-such a comrade, and laughed hysterically at the reply—there swept past us and over us into the open field a long regiment with fixed bayonets and rifles on the right shoulder. Another followed, and another; two—three—four!

Heavens! where do all these men come from, and why did they not come before? How grandly and confidently they go sweeping on like long blue waves of ocean chasing one another to the cruel rocks!

Involuntarily we draw in our weary feet beneath us as we sit, ready to spring up and interpose our breasts when these gallant lines shall come back to us across the terrible field, and sift brokenly through among the trees with spouting fires at their backs.

We still our breathing to catch the full grandeur of the volleys that are to tear them to shreds.

Minute after minute passes and the sound does not come.

Then for the first time we note that the silence of the whole region is not comparative, but absolute. Have we become stone deaf? See; here comes a stretcher-bearer, and there a surgeon! Good heavens! a chaplain!

The battle was indeed at an end.

As far as one could see through the forests, among the splintered trees, lay wrecks of men and horses. Among them moved the stretcher-bearers, gathering and carrying away the few who showed signs of life. The dead were collected in groups of a dozen or a score and laid side by side in rows while the trenches were dug to receive them.

Most of the wounded had died of neglect while the right to minister to their wants was in dispute. It is an army regulation that the wounded must wait; the best way to care for them is to win the battle. It must be confessed that victory is a distinct advantage to a man requiring attention, but many do not live to avail themselves of it.

Afterword:

The Battle of Shiloh took place in an area about one mile to one mile and a half in diameter. For the two armies in forty-eight hours there were 23,841 casualties.

General Ulysses S. Grant described the horror of the scene in his Memoirs:

I could've walked across that field as far as the eye could see and never touched the ground, by walking on the bodies.

It was at that moment I realized that this war could never—that the Union could never be preserved— without complete conquest of the South.

Excerpts from:

Asbury Harpending: The Great Diamond Hoax and Other Stirring Incidents in the Life of Asbury Harpending

—Read the book on Project Gutenberg