California in the Civil War: San Francisco commits to the Union

After the Gold Rush, Chapter 35 -- Detective I.W. Lees, Bret Harte, Reverend Thomas Starr King, Mary Ellen Pleasant, Asbury Harpending, General Albert Sidney Johnston

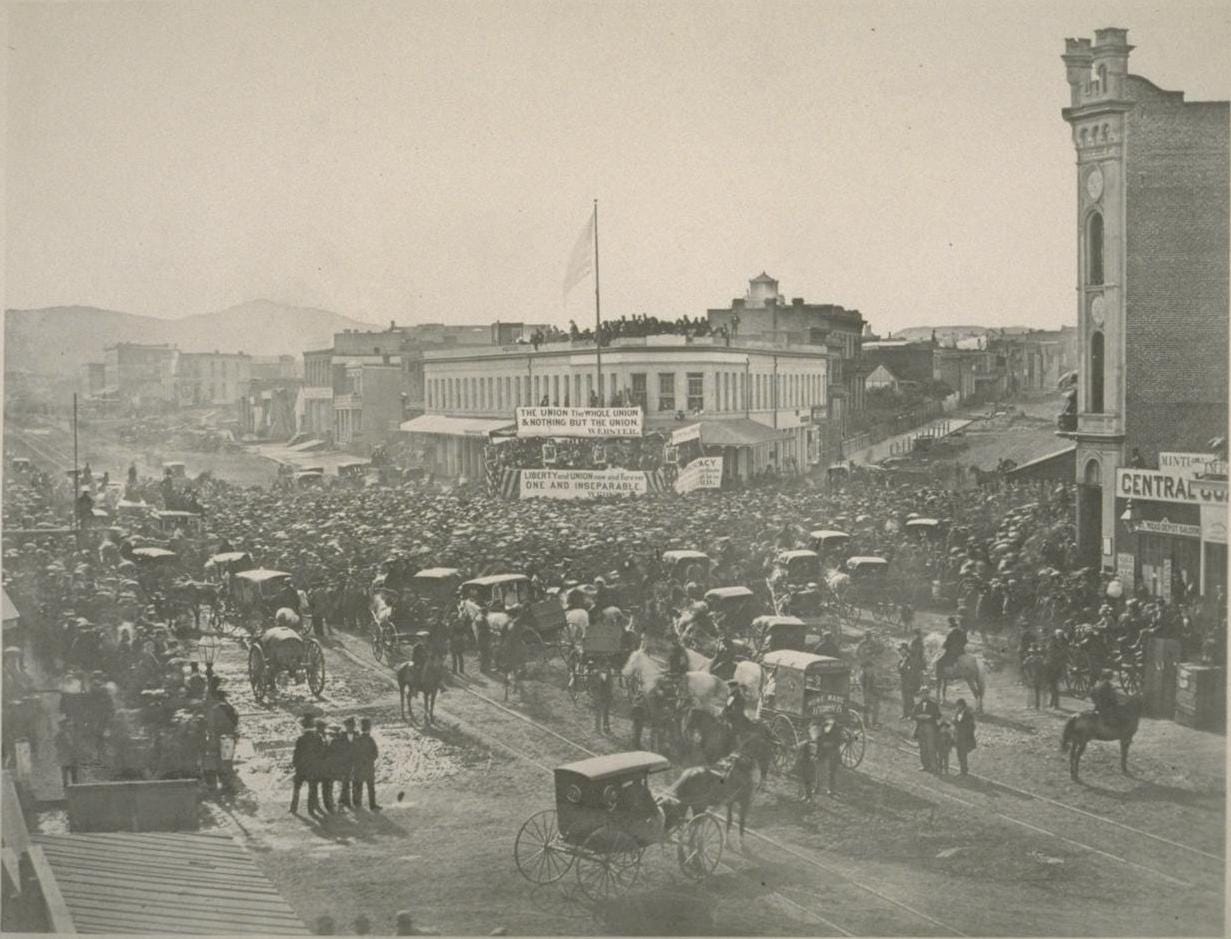

May 11, 1861 — San Francisco Union Square

From every public building and hotel, from the roofs of private houses and even the windows of lonely dwellings, flapped and waved the striped and starry banner. The steady breath of the sea carried it out from masts and yards of ships at their wharves, from the battlements of the forts.

- Bret Harte

Detective I.W. Lees (age 41)

Detective Isaiah W. Lees was worried.

He looked out over the thousands gathered in Union Square under a cloudless sky. Red, white and blue flags waved over the city’s buildings. Union badges flashed on lapels, on hat brims, twisted into scarves.

The American Brass band played, whilst firemen, civic organizations, and every military organization in the City assembled to march: the California Guards; Black Hussars; City Guards; Montgomery Guards bearing flags; horses blanketed with flags, their riders waving flags.

Lees muttered to the two policemen beside him, “There must be twenty thousand here.”

San Francisco loved its parades and demonstrations. But in his ten years on the fledgling police force, Lees had never seen a crowd like this grand Union rally. And with just one police officer per hundred people in the City, the law was hopelessly outnumbered even on the quietest of days.

Which this most assuredly was not.

Worse, conspiracy was afoot. Lees’ intelligence was that Southern Chivs in the Knights of the Golden Circle were gathering arms. It was no secret that General Albert Sidney Johnson himself, who had charge of the Presidio and its considerable weaponry, had deep ties to the South.

The Secesh forces in the city might well take the opportunity to strike a devastating blow. And tinderbox that San Francisco was, a single cannon shot could wreak havoc on the city.

Even as he thought it, Lees had a flash so clear it seemed a premonition: a living image of this entire crowd, trapped by its own sheer numbers in a horrific conflagration. A wall of fire surrounded the street, black smoke poured from windows. Worst of all was the building wave of screams— from men, women, children trapped in burning buildings, begging piteously to be killed before the flames consumed them—

Lees wrenched himself out of the nightmarish vision, to find his palms clammy, his forehead damp. He’d broken into a cold sweat.

“Sir?” The young policeman at his side regarded him, alarmed. Lees shook his head. But while the horrifying vision had dissipated, his anxiety had not.

Fire was every San Franciscan’s worst fear. The entire city consisted of wood buildings, set right up against each other, constantly drying in the sun and winds. A bombardment of an hour would set the town on fire in fifty places. There was already a dry breeze. If a high wind should be added, not at all improbable in summer, there was no human power that would be sufficient to save San Francisco from destruction.

Around Lees, whistles blew, cymbals crashed, and at the signal the crowd processed through the streets. As they marched, men and boys tore down and shredding any palmetto flag they came across. The roofs and balconies and windows of every building for blocks around were alive with cheering, flag-waving throngs.

At the corner of Market and Montgomery stood three huge platforms that had been erected for the speakers, decorated with banners and flowers, with seats for their ladies and other prominent citizens.

One four-horse carriage bore the sign: Pacific Glue Factory: We Stick to the Union!

Another read: The Union, the Whole Union, and Nothing but the Union!

Behind the platforms a strip of muslin bore the painted verse:

The Union of lakes, and the Union of lands, the Union of states none can sever;

The Union of hearts, and the Union of hands, and the flag of our Union forever!

And then down the street appeared another structure Lees had not been prepared to see. The old Empire Saloon, formerly a ship, had been pulled from its piles and was now being trundled, groaning, on a wheeled platform down Clay toward Sansome. The crowd parted for it as the Red Sea, and it came to a shuddering halt in the exact center of the streets.

At the top of the saloon, a human-looking figure swung at the end of a rope hung from the roof. After the initial shock, Lees made it out as a dummy wearing a mask. A banner proclaimed its traitorous name: Jeff Davis.

A deep booing rose up from the crowd as the masses growled and seethed ominously at the foot of the structure.

The small squad of police huddled together, completely outnumbered. “They’ll be pulling the whole thing down any moment,” the younger officer predicted.

Lees’ pulse skyrocketed. Riot. With a crowd this size, any number of people were in could be trampled…

“Or setting it ablaze,” the other officer pointed out hollowly.

Fire, Lees thought again. Please God, not fire. The crowd suddenly surged forward. The saloon rocked on its stilts…

Lees snapped into action. He pulled a set of irons from his belt, and told the other officers, “Be ready and follow my lead.”

He shouldered through the mob, shouting, “Make way! Make way for the police!” He climbed the ship’s stairs to the deck, held the irons aloft… then drew his pistol, dramatically. The crowd quieted, a held breath of anticipation.

Lees approached the dummy, and shouted to it, “Jefferson Davis, I arrest you for high treason!”

Below him, the crowd erupted in a deafening cheer, that grew in intensity as Lees holstered his weapon, and pulled out a knife to cut the effigy down. It fell into his arms and he turned back to the crowd, brandishing the dummy out in front of him, dangling by its rope neck.

“To prison!” Lees shouted.

“To prison!” the crowd echoed.

Lees gestured to the two officers at the front of the platform. “Take him away!” he ordered. The officers scrambled up the platform, took the dummy by both arms…

And hauled it off through the crowd in the direction of the c ity jail, while all around them the crowd cheered.

Lees followed behind, feeling sweat running down his back, and the wild triumph of relief.

However improbably, the “arrest” had worked.

For now.

Bret Harte, Reverend Thomas Starr King

Unaware of the drama taking place just blocks away, Frank Harte was also in a sweat as he stood shivering on the ceremonial platform on Montgomery Street. He’d heard that a staggering twenty thousand people were now in the crowd before him.

The Reverend Starr King had insisted on a patriotic poem for the occasion, which Harte had delivered —and which the Reverend intended to read to this fearsome gathering any moment now.

Harte thought he had never been so terrified in his life.

The Reverend rose and stood, patiently smiling and nodding, until the crowd quieted. “I should like to read for you now a poem by Mr. Francis Bret Harte: The Reveille.”

And then the Reverend’s wondrous voice unfurled, carrying Frank’s words through the air like a clarion call:

HARK! I hear the tramp of thousands,

And of armed men the hum;

Lo! a nation’s hosts have gathered

Round the quick alarming drum,—

Saying, “Come,

Freemen, come!

Ere your heritage be wasted,” said the quick alarming drum.“Let me of my heart take counsel:

War is not of life the sum;

Who shall stay and reap the harvest

When the autumn days shall come?”

But the drum

Echoed, “Come!

Death shall reap the braver harvest,” said the solemn-sounding drum.“But when won the coming battle,

What of profit springs therefrom?

What if conquest, subjugation,

Even greater ills become?”

But the drum

Answered, “Come!

You must do the sum to prove it,” said the Yankee answering drum.“What if, ’mid the cannons’ thunder,

Whistling shot and bursting bomb,

When my brothers fall around me,

Should my heart grow cold and numb?”

But the drum

Answered, “Come!

Better there in death united, than in life a recreant.—Come!”Thus they answered,—hoping, fearing,

Some in faith, and doubting some,

Till a trumpet-voice proclaiming,

Said, “My chosen people, come!”

Then the drum,

Lo! was dumb,

For the great heart of the nation, throbbing, answered, “Lord, we come!”1

Frank thought his own heart would burst through his chest. And as the last words were read, the great audience before him broke into fervent applause and cheers—and with a mighty shout proclaimed the loyalty of California.

Mary Ellen Pleasant

I catered a private party at the Lick House on the day of the parade, and it was something to see, the City coming together to support the Union like that.

However much William Ralston had been wavering on the direction of California, after the shelling of Sumter he went all in for the Union.

That afternoon, a Committee of Thirty-Four, prominent Californians, was appointed, “to detect and suppress treasonable activities against the Union in California.” Ralston was unanimously approved as chairman.

The whole evening was to end with a torchlight procession of what they said was likely to be twenty thousand people or more.

If I was a Secesh, or a Knight of the Golden Circle, I sure as the devil would’ve been thinking twice about “treasonable activities.”

And even I was thinking: maybe, just maybe, we might win this after all.

Asbury Harpending

As night fell and the torchlit procession gathered, requiring the attention of Isaiah Lees and the entire police force, my own group was headed in the opposite direction, with quite different plans of our own.

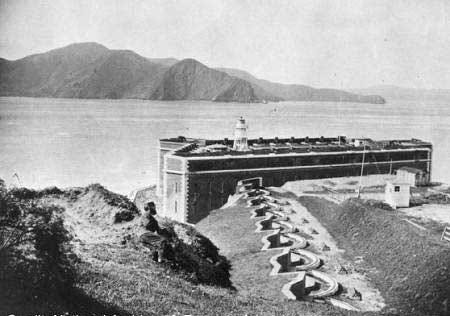

Since its establishment by Spain in 1776, San Francisco’s Presidio had served as a military reservation. It had been that empire’s northernmost outpost in the New World, guarding the harbor from the rival powers of Britain and Russia. When Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1821 the Presidio became a Mexican reserve. During the Mexican War the U.S. Regular Army took possession. The crumbling adobes were replaced with granite block structures boasting smooth bore cannons, and the Presidio grew to the most important Army post on the Pacific Coast, home to several army headquarters and units.

And a treasure trove of military armament.

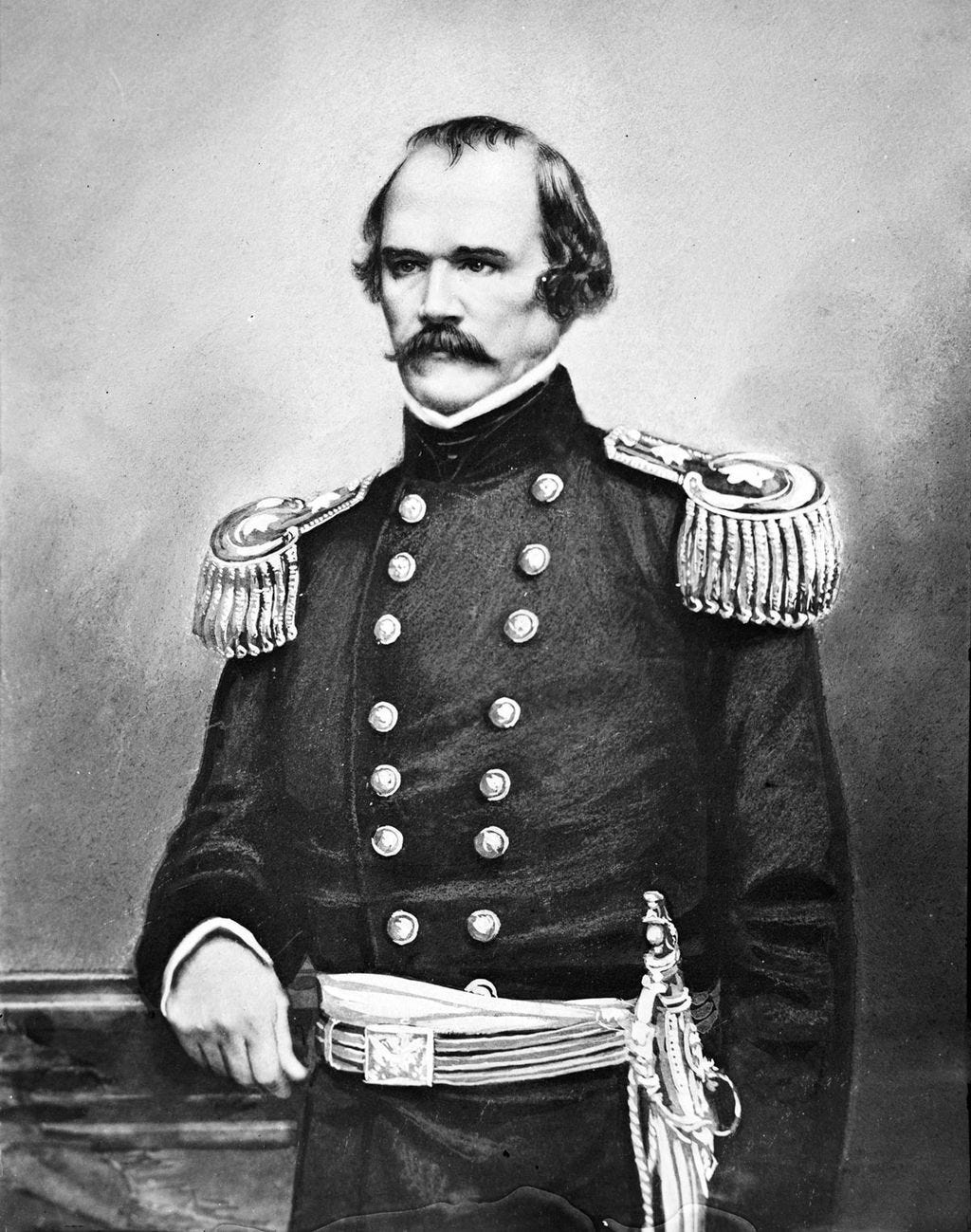

In January of 1861 General Albert Sidney Johnson had been placed there, in command of the Department of the Pacific.

I had met the General but once and was struck by his nobility, a bearing that marks a great leader of men. It seemed to my youthful imagination that I was looking at some superman of ancient history, like Hannibal or Cæsar, come to life again.

Johnston was born in Kentucky but he considered Texas his State. Thus he had a double bond of sympathy for the South. He had been a slaveholder himself, who spoke of abolitionism as “fanatical, idolotrous negro worshipping,” and had written that “where the darky is in any numbers it should be as slaves.”

And this was the man who had the fate of California absolutely in his hands.

This situation had been discussed at several meetings of the Knights of the Golden Circle and it was decided that a committee of three should visit General Johnston. I had become prominent in council through my zeal and discretion, and to my great joy I was named as one of the three.

We would appeal to the General’s Southern honor and enlist him to throw the resources of the Presidio, and his power as commander-in-chief of the army, to our sacred cause. Armed with the Presidio’s abounding military equipment, our army of Southern sympathizers were sufficient in number to beat down any unarmed resistance.

No one doubted the drift of Johnson’s inclinations to the South. But if he refused, we would subdue him with force, and hope he might not suffer in the brief struggle.

The three of us, armed and ready, made our way in the opposite direction of the gathering crowds toward the very northwest corner of the city, and the hills which guarded the dark Presidio.

General Albert Sidney Johnston

In his quarters beside the Officers Club, General Albert Sidney Johnston sat behind his desk, a blond giant of a man with a mass of heavy yellow hair, which in vain moments he was proud was yet untouched by age, though he was nearing sixty.

Before his current appointment he had served as Colonel of the First Texas Rifle Volunteers and General in the Texas Army, as commander of the U.S. forces in the Utah War, and Colonel of the U.S. Cavalry.

He was a career officer through and through. Still, with the secession of the Southern states, he was preparing to resign his post. He did not support secession, but he would not fight against the South.

He had written the letter of resignation already. But there remained one crucial battle to be fought in San Francisco first, and all his senses told him tonight would be the night.

He watched, and he waited.

Finally came a knock on the heavy wood door, and he called out, “Come.”

Three men entered. Johnson knew all of them by sight: avid Southern Chivs, members of the secret Confederate society known as the Knights of the Golden Circle. A group that had the strong support of California’s first and most powerful senator: Doctor William Gwin.

The youngest of the men, Harpending, addressed him first. “We are here on matter of grave urgency.”

Johnson bade them courteously to be seated.

And then drew his own pistol and set it on the desk in front of him.

His three visitors froze, as if they’d never taken his military history into account.

“Before we go further,” Johnson said, in a matter-of-fact, off-hand way, “There is something I want to mention. I have heard foolish talk about an attempt to seize the strongholds of the government under my charge. Knowing this, I have prepared for emergencies.”

He looked each of the men in the face, in turn. “No one who know me doubts my absolute loyalty to any trust. No one—no one—should dream for an instant that my integrity as a commander-in-chief of the army can be tampered with.”

He glanced down at the gun on the desk between them. “I will defend the property of the United States with every resource at my command, and with the last drop of blood in my body.”

His would-be attackers sat there like petrified stoten-bottles. Johnson nodded, and finished softly.

“Go. And tell that to all our Southern friends.”

Much of the above segments concerning Asbury Harpending and General Albert Sydney Johnson is taken from:

The Great Diamond Hoax and Other Stirring Incidents in the Life of Asbury Harpending

—Full book available at Project Gutenberg.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Why subscribe?

After the Gold Rush is a reader-supported publication. To receive a monthly roundup of new posts and support this work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Likes, Comments and Shares are extremely helpful and much appreciated!

Brete Harte, The Reveille