Chapter 32 - Ted & Anna Judah meet The Associates

Collis Huntington, Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins and the Transcontinental Railroad

The names and legends of railroad barons Collis Huntington, Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker and Mark Hopkins are embedded in California history, plastered on its grand hotels, museums, streets, buildings, a major US university— and hundreds of towns and cities. But the real visionary and force behind the Transcontinental Railroad was a brilliant young railroad engineer named Theodore Dehone Judah, who with his wife and partner, Anna Feron Pierce Judah, literally and figuratively moved mountains to make the nation’s dream of a unifying railroad a reality. Their David and Goliath story is a microcosmic representation of the battle between the best and the worst of American instincts and ambition.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

After the Gold Rush, Chapter 32

Sacramento, California: Early 1861

Ted & Anna Judah

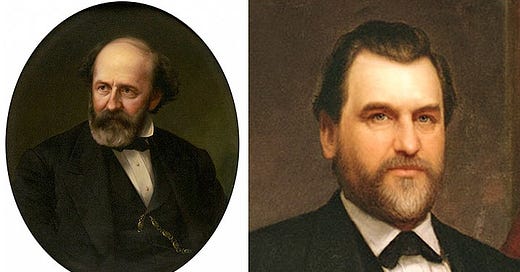

The Associates: Collis Huntington (39), Leland Stanford (37), Charles Crocker (39), Mark Hopkins (49)

The specter of coming war consumed Californians’ attention and delayed Ted’s plans to line up Sacramento investors for his proposed Transcontinental Railroad. But he resolved to use the time to get as prepared as humanly possible, and target the most likely investors.

He had but one lined up: James Bailey, a jeweler, the only truly rich man Ted knew. Bailey had promised to “come in” once Ted had attracted some other solid offers. What he needed now were some big fish Sacramento businessmen.

He and Anna dove into researching their prospects, and focused in on four likely targets: Collis Huntington and his business partner Mark Hopkins; Charles Crocker, and Leland Stanford.

From top left, clockwise: Collis Huntington, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker

They were all shopkeepers with similar stories. Gold had lured them to California in 1849, but they made their practical, modest fortunes by “mining the miners”—providing equipment and staples to the Argonauts. San Francisco being wildly expensive, the four had all separately set up shop in Sacramento. Huntington and Hopkins soon teamed up and built their K Street store of shovels and axes and nails into the largest hardware enterprise in the Pacific. Leland Stanford and his brothers ran a profitable wholesale grocery at Front and L Streets, while Charles Crocker operated a thriving dry goods store.

Huntington and Hopkins were an unlikely but efficient pair. The older Hopkins was miserly, cranky and faddish; he grew his own vegetables and was rumored to eat no meat. He said of himself, “I am a man who cannot create a business, but I know how to make one go.”

He didn’t need to create it. Huntington had enough hustle for both of them. Huntington went out and rustled up goods and deals while Hopkins ran the store and did the books.

Leland Stanford hailed from New York and was the best-educated of the four, the possessor of a law degree. He was handsome, swarthy, and by all accounts devoted to his rather plain wife, though the couple was childless.

And Charles “Bull” Crocker was the loudest and most physical of the lot. He had worked on farms, in a sawmill, and had run his own iron forge before the Gold Rush drew him to California.

The businessmen were quite active in Sacramento politics. Crocker, Hopkins and Stanford had early on been elected and served as city aldermen. The four became acquainted and soon joined forces in the new Republican party, all of them for various reasons, some purely selfish, being opposed to the expansion of slavery. They campaigned for John C. Frémont for president, and the next year Crocker ran for the California Assembly, with Stanford on the same ticket for state treasurer. Their slate was defeated, but the associates became prominent figures in the growing party. They ran Stanford again in the next election, this time for governor. Once again he lost, but he’d gained more votes in the running, and was building up a great deal of name recognition.

Ted and Anna were excited to find the text of a speech of Stanford’s, made during his failed gubernatorial run:

“I am in favor of a railroad, and it is the policy of this state to favor that party which is likely to advance their interests… We are in favor of the railroad by that natural route which the emigrant in coming to this country has pointed out to us.”

“They are already in favor of a railroad by the emigrant route,” Ted enthused to Anna. “And it only makes sense that the push for the road should come from the President’s own party faithful!”

With high hopes, Ted placed an ad in the Sacramento Union advertising a meeting to be held at the St. Charles Hotel on K Street: “To consider questions in connection with the Pacific Railroad.”

Before the meeting, Anna prepared the room as carefully as she had arranged the Railroad Museum in Washington: setting out the Ted’s maps and charts from the Pacific Railway Exhibit on Capitol Hill; pinning up her sketches and paintings illustrating the majesty of the Sierras; as well as laying out the samples of ore, minerals and fossils she and Ted had collected on their Sierra expeditions.

As local merchants and some curious onlookers filed in, Ted was instantly aware of the imposing man in black frock-coat and black tie. He was over six feet tall with a massive frame, sporting a brocade vest with a gold watch chain stretched across his stomach.

Huntington.

Here was his big fish. Now Ted needed to land him.

He took a breath and stepped to the front of the room to welcome the crowd.

From her discreet place at the back of the room, Anna gave him an encouraging smile. And as always, Ted’s jitters faded as he became caught up in his own enthusiasm and the clear logic of the plan.

He asserted his core argument: he had crossed the Sierras twenty-three times thus far, on foot, by horse, wagon and mule, and he was confident beyond any doubt that the route he and Doc Strong had discovered was a practicable one.

He pointed out that if Sacramento was to be the terminus of the great road, it behooved the people of that fair city to take part in the planning.

And he argued for the sheer simplicity of the first step: a survey to present to the new President, demonstrating the feasibility of the route.

“All that needs to be done now is to subscribe $10,000 per mile for the proposed route. And already more than a third of the required amount has been subscribed by the forward-thinking men of five Sierra towns.”

After his enthusiastic appeal, several merchants made pledges. The others held back and looked to Collis Huntington, who had been silent throughout the presentation.

“You’re the man for this, Huntington,” one of them ventured.

Ted waited with bated breath… but Huntington shook his head. “Contributions at a public meeting might do for a Fourth of July picnic, but that will never build a railroad, much less a transcontinental line.”

It was the last word on the matter. There were no more subscriptions offered that night.

But as a crestfallen Ted began to collect his charts and drawings, Anna nudged him and nodded toward the back of the room. Huntington was still there, standing at the back, watching him.

Anna slipped out of the room to leave them alone. Ted set down his charts and walked toward him.

“Mr. Huntington.”

Huntington wasted no words. “You’re going about this all wrong, son. If you want to speak further, come by the store one evening. I’ll invite some friends around.”

Back at home, Ted recapped the encounter to Anna, but paused at that point and said abruptly, “This Huntington is a hard man.”

Anna felt a thrill of warning. If Ted, who rarely had an unkind word to say of anyone, felt anything akin to suspicion, there might be danger indeed.

She had taken particular care looking into “Old Huntington.” Just thirty-nine years old, but clearly the leader of the four businessmen.

He had been born in a shanty in a small valley in Connecticut aptly known as Poverty Hollow, the son of a tinker. At age fourteen he ran away from home to hire himself out as a farm hand, and then traveled to Oneonta, New York and worked as a grocery clerk. He saved all his money for twelve long years, dreaming of his own store, marrying childhood friend Elizabeth Stoddard in 1844. Then news of the Gold Rush propelled him and his small savings to California in March 1849, on board the Crescent City.

But when he and his fellow Argonauts made it through the Isthmus of Panama, there was no ship waiting for them at the other side to take them north to San Francisco.

For three months, the passengers were stranded in the biblical rain and mud of Panama. Death carried off the Americans most fearfully; they were dying at a rate of ten per day, prey to the many horrors of the jungle: alligators, snakes, poisonous lizards, worms, cholera, dysentery, yellow fever, malaria. Huntington hiked thirty-nine miles through the jungle to a village where he used the $1200 he’d brought with him to buy survival supplies: sugar, syrup, jerked beef, potatoes, rice, and some donkeys to carry the goods back to the surviving stranded Americans—to sell at a fine profit.

When Huntington finally reached San Francisco in August, 1849, he’d managed to turn that $1200 into $5000.

A hard man, indeed, Anna thought, and glanced at her ever-optimistic husband. She ventured, carefully, “Then perhaps he is best avoided.”

“But he sees, Anna. He sees the railroad, I can tell. He will be the one to do it with us.” Ted paced the floor. “And you know I am well accustomed to pitting my brains and will against other men’s money.” That light Anna knew so well was back in his face. “He and his associates will understand the politics of it. The railroad must come from the Republican Party, as the living symbol of the Union—”

“Be not too lofty,” Anna begged. “Remember, my love. These are shopkeepers, not visionaries. They will be looking to how they can profit.”

“I will be all practicality,” Ted assured her. “Cloudy days will soon blow over.”

The next evening, tingling with nerves, Ted climbed the stairs to the second-floor offices of Huntington and Hopkins’ hardware store.

There, just as he and Anna had anticipated, sat Charles Crocker, called “Bull” by his friends: a loud, profane, red haired, hard-drinking, two-hundred-and-fifty-pound mountain of a man. Mark Hopkins, older than the others at forty-nine: as thin as Crocker was stout, bearded, sallow, soft-spoken and fastidious. And Leland Stanford: large and deliberate, swarthily handsome, with a square chin and deep-set eyes.

Ted launched into his pitch.

After the men had listened, Huntington asked brief, blunt questions: “What must be done first on the Dutch Flat route? How much will the survey cost? How far will it go?”

Ted answered every question confidently and precisely.

Finally Hopkins cleared his throat. He had said nothing throughout the entire meeting. But this was the man whom friends and employees referred to as “Uncle Mark,” and Ted saw that when he sat forward, the other three looked to him instantly, expectantly.

He stroked his beard. “What I see is a pile of ugly mountains.”

Ted took a breath, and took his best shot.

“Suppose there is no passage. You lose nothing. The government will advance the funds to build a road to the Comstock. Whatever happens from there, you will own the road to the silver mines, and all the tolls the road would provide.”

Ted felt the very temperature of the room change in that moment. Huntington’s eyes glittered, and Ted knew that the man understood exactly what a mining road would mean. A tremendous volume of freight, at extremely high rates, was presently leaving Sacramento and crawling along the snaking, pitted roads of the Sierras. Anyone who could provide a more direct road could charge a premium, and gain a percentage of all the staggering wealth of the mines.

“Help me to run my survey over the mountains,” Ted urged. “With this we can get government support for the company—and you can control the company. If you get control of the traffic to the Nevada mines, you and you alone will control the market. Why, you can have a wagon road if not a railroad!” He was so close to convincing them, he grew reckless, and spoke words he would later come to deeply regret:

“An estimate can scarcely be made of the profitableness of such a road, for no instance of a road with a similar business exists,” he promised. “The profitableness will exceed that of any known road in the world.”

He closed with the strongest argument he had.

“And all for the start-up cost of thirty-five thousand dollars.”

When Judah had gone, the four businessmen were silent for a long moment.

Crocker was the first to say it. “This Judah is crazy as a jaybird.”

“An excess of enthusiasm, to be sure,” Hopkins offered, more temperately.

“So we ditch him,” Crocker said flatly.

Huntington shook his head. “Unwise. Judah is the ass who will pull our cart. He has a decent knowledge of the Washington players. However he managed it, he has the ears of Congress. And as engineers go…”

He did not need to elaborate. Ted and Anna had not been the only ones to do their research. Every man there knew of Ted’s accomplishments.

“There is another factor,” Stanford added, portentously, and paused for a long moment to be sure he held their attention. “Lincoln,” he said. “The President is dead set on a railroad.”

The four talked late into the night.

The next day, Huntington summoned an anxious Judah to his offices. When Ted entered, Huntington sat behind his large desk in a long silence which Ted began to suspect was intentionally designed to fluster him. Finally the businessman spoke.

“We will pay for a thorough instrumental survey across the mountains. No more.”

Ted could barely hear the rest through the rush of blood in his head as Huntington continued.

Huntington and the Associates, plus Ted and James Bailey, would stand the expense of a thorough preliminary survey and to get up the estimates of the cost of building a road, organizing and incorporating a company.

Huntington’s voice was hard as he stipulated, “Your own estimate is $35,000 for the survey. It must be understood that we agree to nothing more than this. We shall wait for the result of the survey and figures as to cost before deciding upon further action.”

Ted rushed home to Anna, and slammed the door behind him in his exuberance. She whirled to him, startled, and he announced in one breath:

“If you want to see the first work done on the Pacific Railroad, look out of your bedroom window. I am going to work there this afternoon, and I am going to have these men pay for it.”

He pulled her to him and, triumphantly, kissed her.

When she was finally able to catch her own breath, she said drily, “It’s about time somebody else helped.”

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Why subscribe?

After the Gold Rush is a reader-supported publication. To receive a monthly roundup of new posts and support this work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

G. F. Keller, The Curse of California: The Wasp, August 19 1882.