The Civil War in San Francisco: Michael, Charles & Gus de Young

After the Gold Rush, Chapter 33

Three of the most fascinating characters of the California Civil War years, and some of the most important builders of the city of San Francisco, were an unlikely teen/pre-teen trio of Jewish brothers: Charles, Gus, and Michael de Young. Their father supposedly died on the family’s ocean journey from St. Louis to San Francisco, leaving the boys’ mother Cornelia, aka Amelia, to support the family in one of the only professions allowed to women of the time. But she raised the boys with tales (that may or may not have been true) of their family’s aristocracy, which the young de Youngs took to heart as they imagined and pursued their own newspaper empire. Their rags-to-riches tale is a classic and true American myth, complete with violence, scandal, madness—and murder.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning.

Subscribe for free to get monthly roundups of new posts and to support this work:

1 Note on photo

After the Gold Rush, Chapter 33

April 25, 1861: San Francisco, California

The de Youngs: Charles (age 14), Gus (age 13), Michael (age 11)

Crowds massed on the sidewalks and streets in front of newspaper buildings to read the news posted on blackboards in front of every newspaper office.

Michael, Charles and Gus de Young pushed and squirmed through one of the solemn crowds mobbing the fronts of newspaper offices, and stopped at the sight of the one word that said it all.

The headline shouted:

WAR!!!!

The dispatch was in twelve decks, the largest line Michael had ever seen.

The brothers stood stunned, reading of the shelling of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. The thirty-six hour-long assault had taken place ten days previously and the news had only just reached the Pacific Coast.

President Lincoln had already called for 75,000 troops “To put down a domestic insurrection.”

The crowd all turned to the news office door as a man stepped out, holding a news sheet. All crowd noise hushed as he began to read aloud the latest dispatch :

“Everywhere in the North, flags and bunting hang from every window and porch rail; in Pittsburgh, lampposts sport nooses, sashed with the slogan ‘Death to Traitors!’ The word seldom spoken as states seceded is now on every lip. The battle has galvanized both sides. Southerners, who are seldom reluctant to boast about their fighting skills or to invent occasions to demonstrate them, have been crowing like a rooster who has made a thousand suns arise….”

After the newsman had read out the communiqué, Charles insisted that the brothers go around to the other news offices to read the posts and see how the different papers were reporting the event. As Charles had taught him, Michael took notes on the political leanings of each paper, and which non-California journals each paper quoted.

The Bulletin: “Rubicon crossed. The great news reached us at a moment that we were required to stop the presses.”

The Alta California: “The people generally agree a great calamity has fallen on the land and that the great experiment of our government might end now after only eighty-five years of trial.”

The Atlanta Confederacy: “If the fanatical Nigger Republican North is resolved to force war upon us, we are ready to meet it.”

The Columbus Daily Capital City Fact: “All squeamish sentimentality should be discarded, and bloody vengeance wreaked upon the heads of the contemptible traitors.”

After the brothers had made their rounds of all the major newspapers, Charles finally let them head home. They passed under palmetto flags already flying from Secesh homes and businesses in celebration.

Charles was brooding. “This is a scoop that could have made us…”

He didn’t have to finish the sentence. His brothers had heard it often enough. “If we’d had our own paper.”

But Charles went on. “Are we in the Dark Ages, that we get this news scribbled on chalkboards rather than printed in a mid-day extra edition? What fools these editors are. And—twelve full days after the fact!”

The report of Fort Sumter’s fall had taken twelve days to go by telegraph to Fort Kearney, then by Pony Express to Sacramento and by telegraph again to San Francisco where it arrived on April 25, 1861.

“The world could end and we would have no idea of it for weeks,” Charles summed up in disgust.

Gus ventured, “With war, perhaps it will be better sometimes not to know everything so quickly.”

Charles ignored this, as he increasingly ignored anything Gus had to say. “We need to be inside the telegraph offices,” he fumed. “We need the news before it’s posted.”

They had reached Fifth Street, where they lived at number 15. A gang of boys lounged on the street corner, and there was a stirring in the pack as they saw the brothers coming. Michael stiffened, his fists already clenching at his sides.

“Hey de Young!” one shouted. “Your ma home? I got two bits.”

Charles flushed bright purple. “Out mother is a seamstress.”

The boys laughed and hooted. The biggest of them taunted, “That ‘sew?’ I heard you ‘sew’ with her, Gussie—”

Before he could complete the sentence, Charles launched himself at the taunter with fists flying. The other de Youngs were right behind, tackling the boy, surrounding him, kicking him in the head, in the stomach, in the groin.

The rest of the boys turned tail and fled, but the de Youngs were too intent on the beating to notice. In between kicks, Charles raved: “Our mother is descended from aristocracy. One day we’ll own this whole city.”

Finally the boy on the ground lay still.

Michael felt something wet on his face and reached up absently to brush it off. His fingers came away red.

Charles gasped in, catching his breath, and looked up at the rooming house, the drawn blinds at their window, which all the boys knew meant they were forbidden to enter. Presently he turned. “Let’s go see what news there is at the docks.”

His brothers followed him down the sidewalk, stepping around the fallen bully, leaving him bleeding and moaning on the ground.

Why subscribe?

After the Gold Rush is a reader-supported publication. To receive a monthly roundup of new posts and support this work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Share this post:

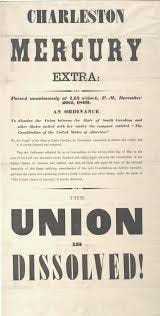

I deeply regret that I can find no photos of the teenaged de Youngs, but this charming photo of newsies depicts boys of the same panache doing the same job that Charles, Gus, and Michael were doing at these ages.