One of the great joys of researching and writing this novelized history of California is discovering the complicated, intimate connections between the people I’m writing about. Anyone reading this newsletter is familiar with American icon Mark Twain, born Samuel Clemens. Many will be familiar with mining baron George Hearst, at least from David Milch’s genius TV western series Deadwood. Milch portrayed Hearst as a supervillain, superbly realized by Gerald McRaney. But that’s not what I remembered of George Hearst from my history classes at Berkeley, and in my extensive research I’ve never come across a single first person account that squares with George Hearst as a villain. I’m personally much more interested in Hearst’s wife, Phoebe, the teenage bride who grew up to be one of California’s leading philanthropists, but while I disagree with his politics I’ve found a lot to love in George, too.

I’ve been delighted to read of his friendship with the young Mark Twain, forged in that great melting pot known as the Comstock. Technically located in Nevada, the Comstock, consisting of Virginia City and Gold Hill, was so inextricably tied to San Francisco’s financial and social life that it was called simply “Above” to San Francisco’s “Below.”

Men from workers to shopkeepers to millionaires commuted from “Below” to “Above” —before the railroad, via horse and carriage, mule and wagon, or on foot — leaving wives and families behind in the city (which I highly suspect accounts for the independence of San Francisco women!)

As with all the vignettes in After the Gold Rush, these scenes and dialogue are taken directly from first and second person source material.

After the Gold Rush, Chapter 51

June 1862: Virginia City, Nevada

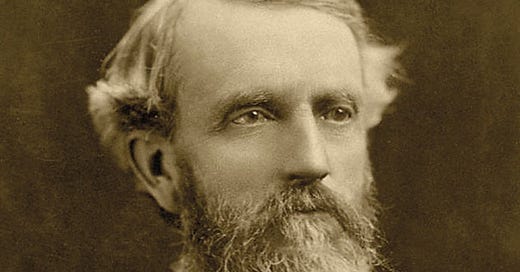

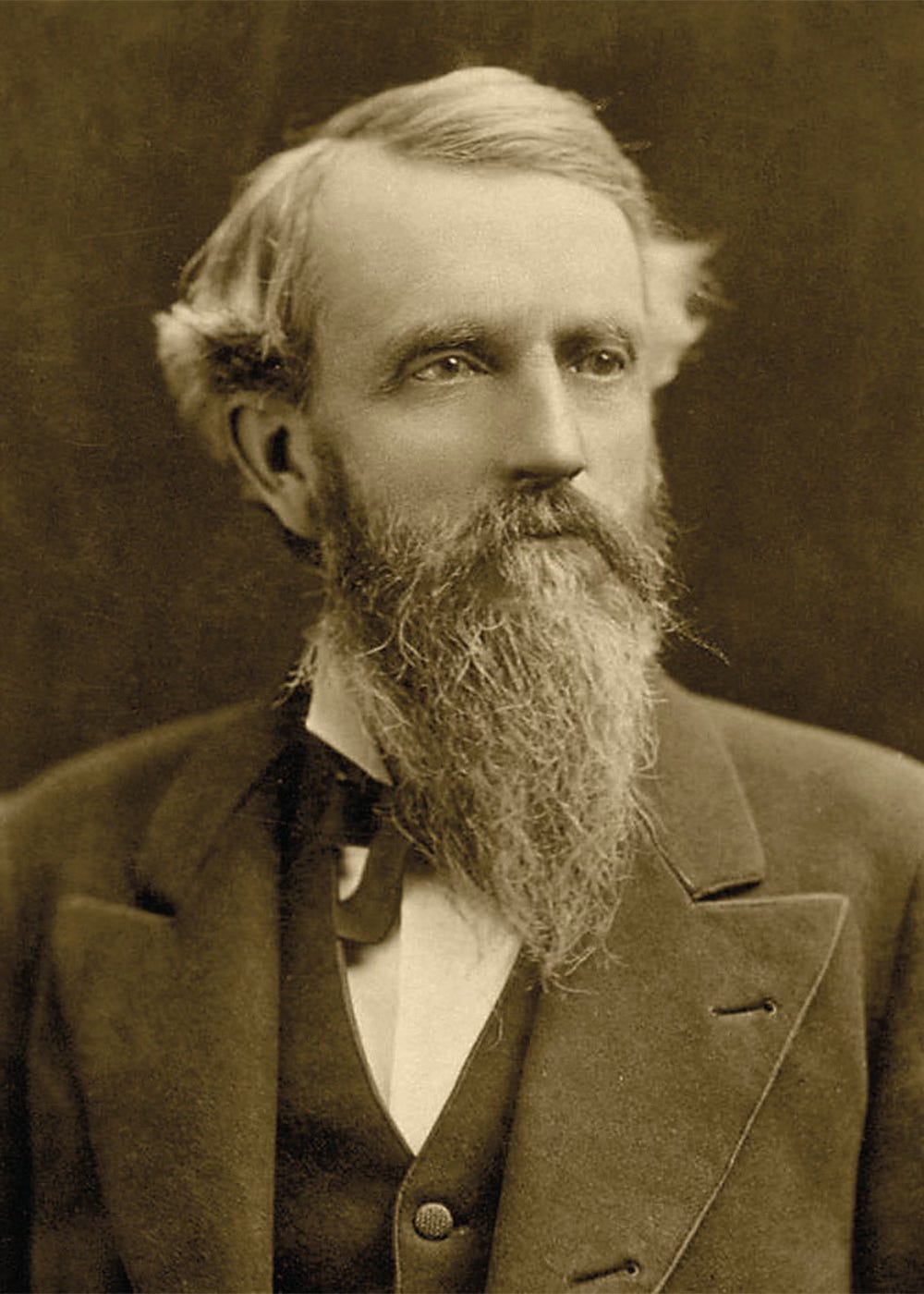

George Hearst (40)

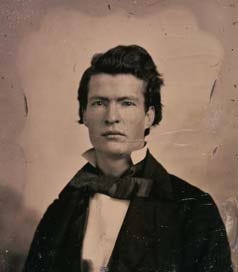

Samuel Clemens (25)

It was an assemblage of two hundred thousand young men—not simpering, dainty, kid-gloved weaklings, but stalwart, muscular, dauntless young braves, brimful of push and energy and royally endowed with every attribute that goes to make up a peerless and magnificent manhood—the very pick and choice of the world’s glorious ones.

- Mark Twain, Roughing It

In his upstairs suite of the Gould & Curry building, George Hearst frowned into his open wardrobe and muttered, “Where in blazes is my shirt?”

He didn’t a’tall care for fuss and furbelows. But it was his last night in Virginia City before he returned to Missouri, and he was making an effort, for Phoebe’s sake—even if she warn’t here to see.

Admittedly he’d had a few celebratory drinks last night. But he was sure he’d hung up his “biled” white shirt the night before.

Now nothing but his everyday miner’s calico confronted him.

He sighed and reached for the cleanest of the shirts.

Before he left the room, he scooped up gold coins from a bureau and filled his pockets, then descended the stairs of the three-story white and brick mansion that also housed the offices of Gould & Curry mines.

He looked about him with satisfaction at the elegant wallpaper and chandeliers, the airy parlors and porches. As the Gould & Curry’s superintendent, George had built the mansion himself, two years ago. The opulence was meant to reassure investors of the mine’s solvency. But now he saw it as Phoebe would when she visited, and was pleased.

As he opened the front door, the house shook with a blast. George paid it no mind. There was an almost constant booming of explosives from the mines.

Outside the house, in the dusty and unpaved street, ragged men waited on doorsteps, skulked on the plank walk. They shuffled up to George, mumbling “Howdy” and “’Gratulations.” George shook hands with all of them, and each one turned away smiling—as he found himself holding a double-eagle gold piece.

They lined up most every day, knowing George was good for a handout. He couldn’t help himself. He knew what the work was, the dirt and loneliness and heartache of it. And tonight he had even more reason to share the wealth.

The last in line was a younger man, scruffily bearded, wearing a long beige duster, a revolver stuck in his belt. George was on the verge of handing him a coin when he recognized Sam Clemens. His hand closed over the double eagle before Sam could grab it. “Get away with you, Sam,” he warned.

“I need it just as bad as t’others,” Sam protested.

George shook his head, not buying.

The youngster had shown up in Nevada City about a year ago, and in a town full of eccentrics, he was quickly making his name as a character. He’d come to work for his older brother, Orion Clemens, the new Secretary of the Nevada Territory. But Sam had quickly abandoned that post for the mines. He had the silver fever, just like a thousand other young men, recklessly sure that he could grab a quick fortune from the dusty land. But he had something else, too, and not just that he was endlessly entertaining. There was something shining about him.

Under the long coat he was dressed in coarse trousers slopping half-in and half-out of heavy cowskin boots. His bushy head was topped by his habitual rusty slouch hat. But this evening instead of his usual dusty flannel shirt, he wore a gleaming starched white shirt, hanging about two sizes too big for him.

George looked closer. “Is that my shirt?”

Sam shrugged, defensive. “Wanted to look good for your fare-thee-well.”

George laughed. It was impossible to stay angry with the boy. “Well, it’s the on’y time you were ever well-dressed in your life.”

The two fell into step, headed down C Street toward the saloon, and Sam returned to the subject of money.

“By George, George, if I just had a thousand dollars I'd be all right! Now there's the ‘Horatio,’ for instance.” Sam was slow to speak, like an engine warming up… with the longest drawn-out drawl George had ever heard. But once he got going, the words tumbled out like water over a sluice. “There are five or six shareholders in it, and I know I could buy half of their interests at, say $20 per foot, now that flour is worth $50 per barrel and they are pressed for money, but I am hard up myself, and can't buy. And in June they'll strike the ledge, and then ‘good-by canary,’ I can't get it for love or money.”

He flung his arms out, appealingly. “Twenty dollars a foot! Think of it! For ground that is proven to be rich. A thousand dollars, George….”

“Ain’t going to do it, Sam.”

Sam stomped on ahead, ranting to himself. “Don't you know that undemonstrated human calculations won't do to bet on? Don't you know that I have only talked, as yet, but proved nothing? Don't you know that I have expended money in this country but have made none myself? Don't you know that I have never held in my hands a gold or silver bar that belonged to me? Don't you know that it's all talk and no cider so far?”

He stopped in the road, struck an orator’s pose and declaimed,

“But-but—in the bright lexicon of youth,

There is no such word as Fail—

and I'll prove it!”

He started to turn back to George, then stopped still, staring out at the view. The flat, sandy desert, surrounded on all sides by such mountains…

George joined him and stood with him in contemplation.

“These mountains. These prodigious mountains…” Sam said dreamily. “You gaze at them awhile, and… sometimes you start mentally measuring ‘em and comparin’ ‘em with things of smaller size and you begin to conceive of their grandeur, and next to feel their vastness expanding your soul like a balloon. You find yourself growing, and swelling, and spreading into a colossus… I say—when this point is reached, you look disdainfully down upon the insignificant village of Carson, reposing like a cheap print away yonder at the foot of the big hills…and in that instant you are seized with a burning desire to stretch forth your hand, put the city in your pocket, and walk off with it!”

George shook his head, marveling. “You ain’t a miner, Sam.”

Sam scowled. “The hell ah’m not.”

“You ain’t.”

“But I could be, with a thousand dollars. Only you won’t do for a friend what you do for any odd fellow on C Street…”

“It’s not in you,” George groped for what he wanted to say, what he knew. “This mining— it’s the on’y thing I can do. You find what you can do.”

Sam stood, silent, eyes drooping. George thought he might have fallen asleep standing up. But then he threw up his hands.

“Then let’s get drunk.”

…

The saloon was packed with well-wishers. For once George was not the one buying drinks.

Across the room, Adolph Sutro raised his glass in a silent toast. George nodded to the cigar maker, who had proved to be a surprisingly shrewd engineer.

Then George turned and sipped his whisky, watching the dancers on the floor. Sam was in the center of the sets of couples. It was the damnedest dancing George or maybe any man had ever seen.

In changing partners, whenever Sam saw a hand raised he would grasp it with great pleasure and sail off into another set, oblivious to his surroundings. Sometimes he would act as though there was no use in trying to go right or to dance like other people, and with his eyes closed he would do a hoe-down or a double-shuffle all alone, talking to himself. “Nossir, I never dreamed there was so much pleasure to be obtained at a ball.”

By the second set, most of the crowd was watching him, dying with laughter, and all the ladies were falling over themselves to get him for a partner.

When Sam collapsed on a seat beside George, George nodded knowingly. “You need to get yourself a woman.”

“I got women,” Sam growled, with all the insecurity of youth.

“The right woman,” George amended. “A woman good for you as mine is for me.”

Sam slapped his knee with a snort. “Now there’s a thing. Can’t figure who’d marry you.”

George chuckled, unperturbed. “She is fine. No airs a’tall. But no one like her in the whole West, just the same. She’s better’n me, for a fact. You’ll see what she makes of herself.” He smiled, thinking of it.

Sam huffed. “I want a good wife. I want a couple of ‘em if they are particularly good. If I were settled, I would quit all nonsense and swindle some poor girl into marrying me. But I wouldn’t expect to be worthy of her. I wouldn’t have a girl I thought I was worthy of. She wouldn’t do. She wouldn’t be respectable enough—”

“Well, you won’t be worthy of her,” George agreed. “But you’ll do your damnedest to be worthy.”

Sam started to protest, and George ended it firmly.

“I’d bet you—if you had any damned money. But you wait and see.”

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Why subscribe?

After the Gold Rush is a reader-supported publication. To receive a monthly roundup of new posts and support this work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.