Remembering Horst Wessel

After the Gold Rush

The 22-year old Nazi activist’s 1930 murder was used by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and the Nazi party to create a martyr for Hitler’s movement.

Born in 1907, in Bielefeld, Germany, Horst Wessel grew up as the son of a pastor and became a charismatic member of the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party who “was interested in talking to the other side,”

As a teenager he founded his own youth group, the Knappschaft, the purpose of which was to "raise our boys to be real German men.”

Wessel was recognized by Joseph Goebbels and the Berlin Nazi hierarchy as an effective street speaker, so much so that in January 1928, Wessel was sent to Vienna to study the National Socialist Youth Group and the organizational and tactical methods of the Nazi Party there. In July 1928, he returned to Berlin to recruit local boys and young men, speaking at 56 NSDAP events in 1929.

In his book The Making of a Nazi Hero: The Murder and Myth of Horst Wessel, professor of European history at Newcastle University Daniel Siemens writes:

“He basically was a good bridge builder between traditional conservative leaders and theoretical Nazis. And that’s what made him particularly useful after his death, as someone who could combine and bring people together posthumously.”

The National Socialists and the Communists spread conflicting accounts of Wessel’s 1930 shooting, still unclear today. Several members of the Communist Party were recruited by Wessel’s landlady to rough him up over a dispute over unpaid rent. Wessel’s SA group often brawled with Communist Party members, and these men may have decided to take action further when they learned Wessel was their target

Goebbels seized on the murder as an opportunity to create '“a young martyr for the Third Reich” (as he wrote in his diary immediately after receiving the news of Wessel's death.)

Wessel was buried in Berlin on March 1, 1930, with many of the Nazi elite in attendance. The funeral was filmed and turned into a major propaganda event by the Nazi Party. Goebbels claimed the funeral was watched by 30,000 people.

Wessel became a propaganda symbol in Nazi Germany as a martyr of the Nazi cause. The “Horst Wessel Song” became the official anthem of the Nazi Party and later the German co-national anthem, along with the first verse of "Deutschland Deutschland über alles." His elaborate memorial became a pilgrimage site. Numerous biographies and films followed. And of course, his “assassination” was used by the Nazis as a justification for rounding up Communists and other detractors of the regime.

Which were legion, of course. Here’s one, for sorely needed inspiration today.

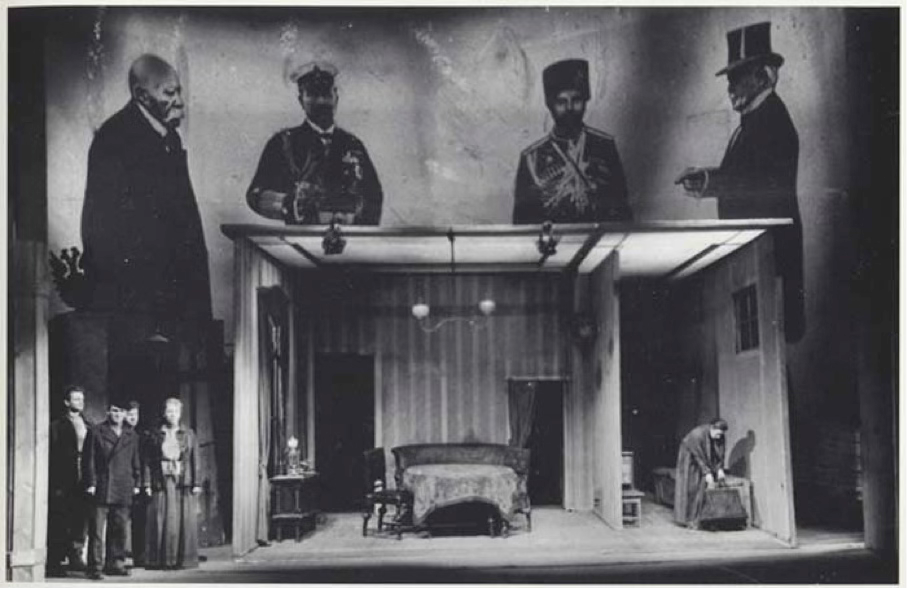

My theater friends may recall that the great German playwright, director and screenwriter Bertolt Brecht 1 wrote his 1935 essay “The Horst Wessel Legend” after fleeing Nazi Germany in 1933 (soon after, all Brecht’s works were thrown into the flames during the book burnings of 1933.)

Brecht was dedicated to exposing fascism’s mechanisms, and analyzed how the Nazis constructed Wessel’s cult of personality. He wrote his satiric Kälbermarsch to the melody and some text of the Horst Wessel Lied:

Following the drum

The calves trot

The skin for the drum

They deliver themselvesThe butcher cries; The eyes tightly closed

The calf marches, with calm and steady step

The calves whose blood already flowed in the slaughterhouse

March in spirit within his ranksThey raise their arms

They show them

The hands are bloodstained

Yet still emptyThe butcher cries: The eyes tightly closed

The calf marches, with calm and steady step

The calves whose blood already flowed in the slaughterhouse

March in spirit within his ranksThey wear a cross in the front

On blood red flags

This for the poor man

Has a big catch*The butcher cries: The eyes tightly closed

The calf marches, with calm and steady step

The calves whose blood already flowed in the slaughterhouse

March in spirit within his ranks

*This is a play on words in German: If something has a catch it has a "Haken" (a hook) The swastika in German is a hooked cross, ein Hakenkreuz.

So what does all this have to do with California history? I’m so glad you asked.

As war ramped up in Europe, Brecht moved his family around to various Scandinavian countries while awaiting a U.S. visa. In May 1941, the Brecht family was able to flee to California, where they rented a bungalow in Santa Monica.

By the late 1930s, the Westside of Los Angeles had become a thriving expatriate colony of European intellectuals and artists, referred to as "Weimar on the Pacific".

Brecht's old Berlin theater friend Salka Viertel, hosted frequent salons where European emigres could mingle with Hollywood luminaries. Though her parties, Brecht met actor Charles Laughton, and the two artists collaborated on Life of Galileo.

Shortly after Brecht co-wrote the screenplay for the Fritz Lang-directed film Hangmen Also Die! (1943) which was loosely based on the 1942 assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, "the Hangman of Prague" - Heinrich Himmler's right-hand man in the SS and a chief architect of the Holocaust.

Brecht has always been a literary and political hero of mine, and seems a great antidote to what is bound to be a relentless flood of present-day propaganda in the news today.

I’ll start gathering some YouTube links and articles and to post here, and continue with his very relevant life and professional history in another post.

I feel better already.

—Alex

After the Gold Rush explores California history, through the novelization of real events and people—not just white men —with occasional urgent detours into world history we really don’t want to be repeating.

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

Famous plays of Brecht to start with:

Life of Galileo, Mother Courage and Her Children, The Good Person of Szechwan, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, The Caucasian Chalk Circle, Fear and Misery of the Third Reich, The Threepenny Opera