1866 - the Memphis and New Orleans massacres

After the Gold Rush - a novelized history of California

It was an absolute massacre by the police… perpetrated without the shadow of a necessity.

- General Philip Sheridan

After the Gold Rush - Chapter 138

May 1-3, 1866 - San Francisco, California

Mary Ellen Pleasant

We gathered at AME Zion that morning to hear the news read out. First there was stunned silence. Then wails and shouts and shrieks of outrage.

It was reported as starting with “a shooting altercation between white policemen and Black soldiers recently mustered out of the Union Army.”

It ended as a massacre.

Mobs of white civilians and policemen rampaged through Black neighborhoods in Memphis, burning the houses of freedmen, attacking and killing Black men, women, and children. Forty-six Black dead, and two white. Seventy-five injured. Over one hundred of us robbed. Five Black women reported rape, though the papers used every word they could think of to avoid the true one, and you know that five was only a fraction of the real total. Ninety-one Black homes and every Black church and school in the city were burned.

We all knew what it was. The planters were hell-bent on crushing the life freedmen were building in Memphis, and driving us back to work the plantations.

Federal troops were sent to quash the violence and peace was restored on the third day. Our community went into mourning.

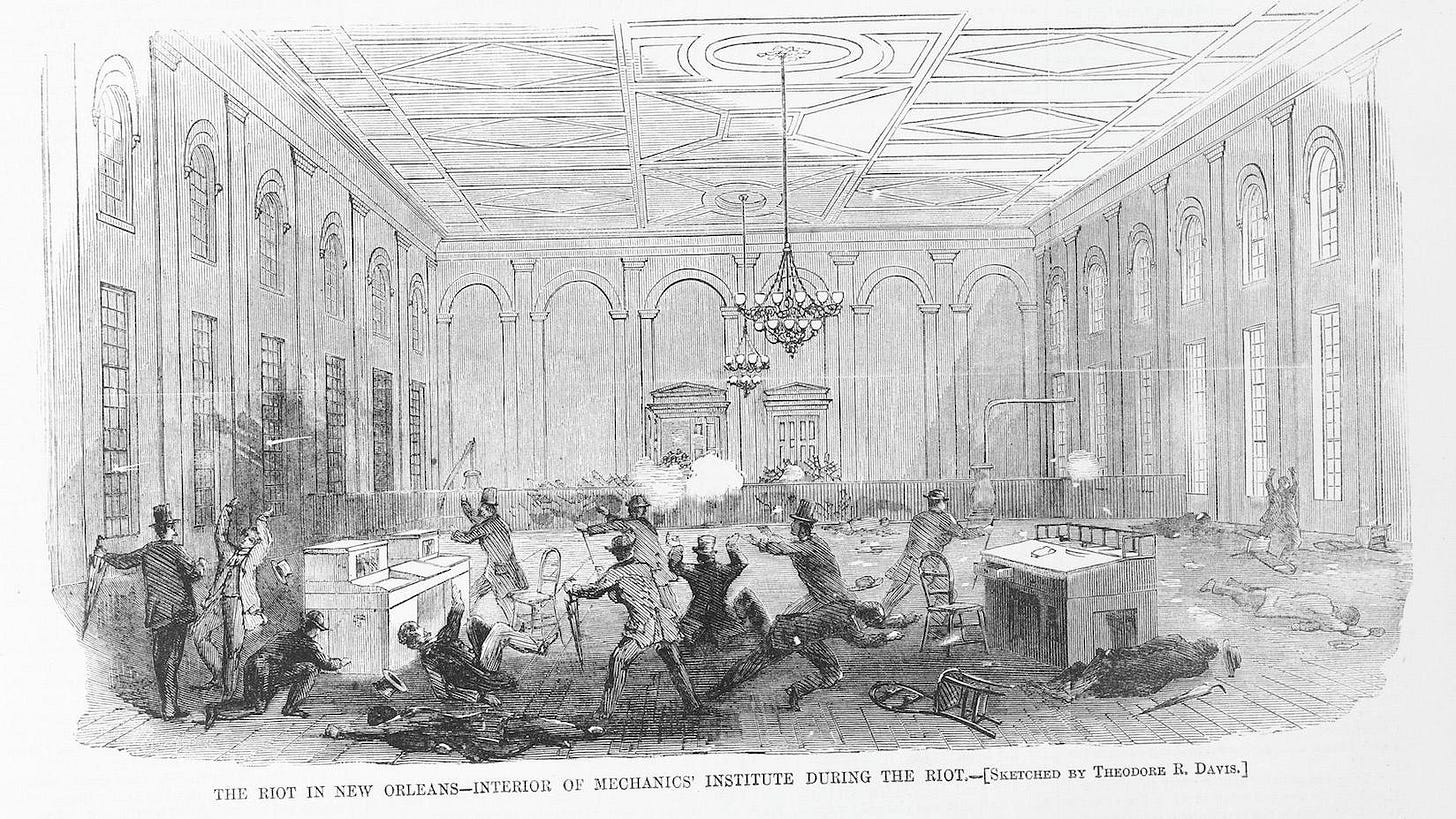

Then it happened again in July, in New Orleans.

The Union Army had maintained martial law in New Orleans during the war. But in May of 1866, martial law ended and Mayor John T. Monroe was reinstated as acting mayor. Monroe—an active supporter of the Confederacy. It was happening all over the South. And just like in the rest of the South, the Louisiana state legislature passed the Black Codes and refused to extend voting rights to Black men.

Louisiana Republicans called for a Constitutional Convention.

On the day, a delegation of one hundred and thirty Black New Orleans residents marched behind the U.S. flag toward the Mechanics Institute, where the Convention was to take place. Mayor Monroe organized a mob of “ex” Confederates, white supremacists, and members of the New Orleans police and led them to the Institute to block their way. The mayor claimed his forces were there to put down any unrest that may come from the Convention. Obviously the real reason was to prevent our delegates from meeting.

In the ensuing massacre, the white mob killed forty-four Black delegates and three white Republicans. A total of 150 Black casualties.

And Andrew Johnson, the President of the United States, publicly blamed the massacre on those who had called for Black suffrage in the first place: “Every drop of blood that was shed is upon their skirts and they are responsible.”

After New Orleans, I was done mourning.

That night I went out in the dark and stood under the moon and cursed them all. I called on all the Loa and all the Ancestors and asked for revenge.

In the days after, I fantasized about doing it myself.

I couldn’t look at a white person without envisioning violence. Every time I was at a job, now, I thought of killing. Poison in the soup at one of Ralston’s balls. I could do a lot of damage before they took me down.

Finally I left the city. I knew I needed to be alone. I was afraid of what I might do without thinking. I went to my house out of the city, Geneva Cottage on the San Jose Road.

There, in the isolation, I drank. I howled. I wept.

Thomas came to me three days later. He had been down at the New Idria. The mine was in the center of the state, nearly two hundred miles away. He must have left as soon as he heard the news.

I heard the door open, and then he was there, a shadow in the doorway. I had lit no lamp. It was only darkness I craved.

His voice was tense. “I was as quick as I could manage—”

He stepped toward me, but I guess he caught a glimpse of my face. He stopped. Which he damn well should have. I wasn’t sure I wanted him to touch me. Or any man, much less any white man. But he knew enough to keep his distance, which was something.

He spoke slowly. “My anger cannot match yours. But it joins yours—”

I shot him a look and he fell silent. He could not conceive of my anger.

After a time, he asked quietly, “What are you planning to do?”

My voice was cold. “What makes you think I am planning anything?”

“I know you. And if it were me, in my country, I would be going to war.”

I reached to the lamp on the table beside me and turned on the light.

And I let him see me. Real me. Without powder. Without Erzulie’s glamor.

We looked across the room at each other. My throat was so dry I could barely get the words out.

“I wanted you to see me.”

And he shook his head, with a soft laugh. “My love. I’ve always seen you.”

I was trembling all over, but I kept my voice even.

“You want to stay with me, you need to keep a lower profile. No committees. Nothing except your name on paper. Just business. You can’t have anyone coming after you, cause they’re going to find me. I’m not going to hide any more.”

“I don’t care—”

“They can’t know we’re in business. That’s my final word on it.”

The tenderness in his voice nearly undid me. “I’ll do what I need to do.”

Read After the Gold Rush from the beginning:

All material © Alexandra Sokoloff

Share this post:

After the Gold Rush is the epic story of the building of San Francisco as novelized history, told by the real people who built it, in their own words, from original source material such as newspapers, letters, court documents and the novels they wrote themselves.

Part 1 brings to life California’s rarely discussed Civil War and Reconstruction years. The characters are familiar American icons like Mark Twain, Governor Leland Stanford and mining baron George Hearst—and many more real historical figures who don’t happen to be straight white men but deserve to be equally well known.

California’s pioneers, dreamers, barons, immigrants, californios, civil rights leaders, villains. They knew each other, married each other, fought each other, and killed each other in “the most picturesque city, in the most romantic state, at the most dramatic moment in the history of the Republic.”

Why subscribe?

After the Gold Rush is currently available only online. Subscribe to get full access to all current chapters, photo and source material links, and the website.